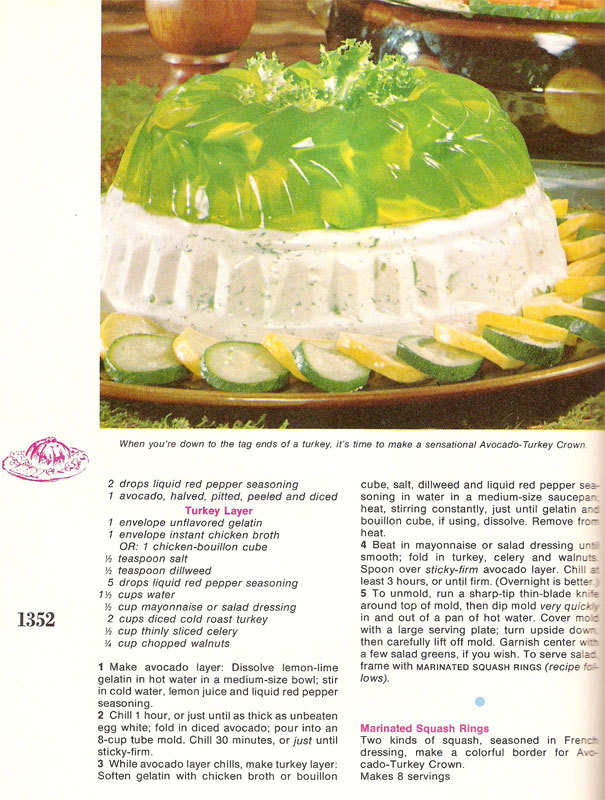

Rei N. sent in this vintage Wonder Bread ad from 1968, found here:

Text:

A pretty girl knows how to succeed with boys without half trying. But she’s got a lot going for her–marvelous new cosmetics, smashing fashions, and Wonder Bread. Wonder Bread? Wonder Bread! Wonder’s the neatest way to trap a boy since…well, since apples. Try tempting him with his favorite Wonder sandwich. He’ll bite. And–ZAP!–you’ve got him.

Well. Huh.

As Rei says, there’s the nice cultural trope about women “trapping” men (ZAP!), apparently since the time of Eve and her apple (nevermind that, according to Genesis, she was made for him because he was lonely, and she didn’t use an apple to trap a boyfriend, and all the other logical stuff). It’s also interesting that they don’t even bother to imply that some of the things she’s “got going for her” might include personality, manners, etc.–they’re all external, purchased assets.

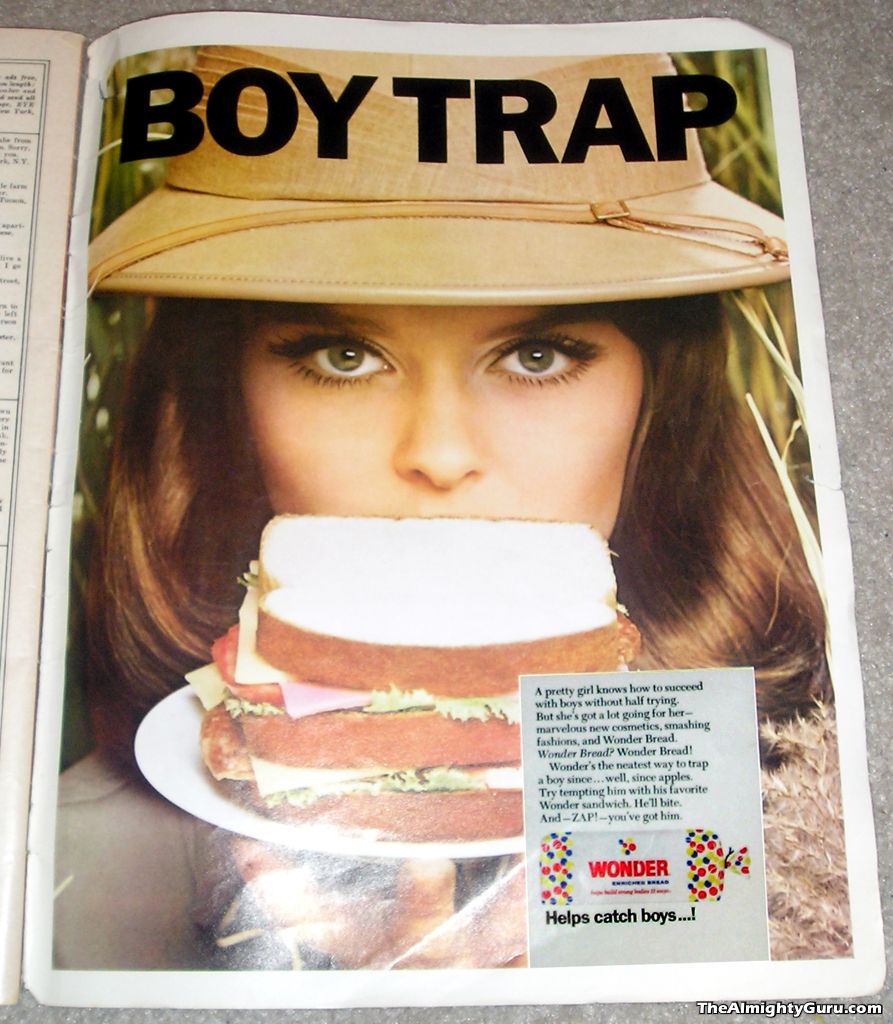

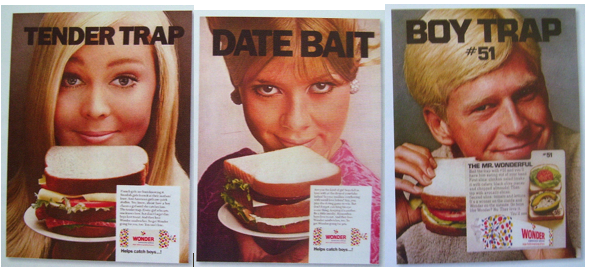

Apparently Wonder Bread put out a whole series of these types of ads. Here are there others, which I found in this paper:

The whole “the way to a man’s heart is through his stomach” message, as well as the clear assumption that women prepare meals and men consume them (note the man on the right is the only person seen eating as opposed to offering a sandwich), is nice too.

Thanks, Rei!