Jason S. sent in this (pretty hilarious) three-minute “ad” for Zima. While modern motherhood takes many different forms, the ad is a great illustration of one stereotype of the modern mother:

So, according to the ad, moms…

1. …are middle class. She and her husband can afford a nice, new minivan.

2. …provide their children with active social and educational lives. Since they live in the suburbs, she spends a lot of time shuttling them from place to place.

3. …are frazzled. Likely a full time wage worker and the primary care taker for the children, the condition of the inside of the minivan suggests that she does not have time to clean or organize her family’s life.

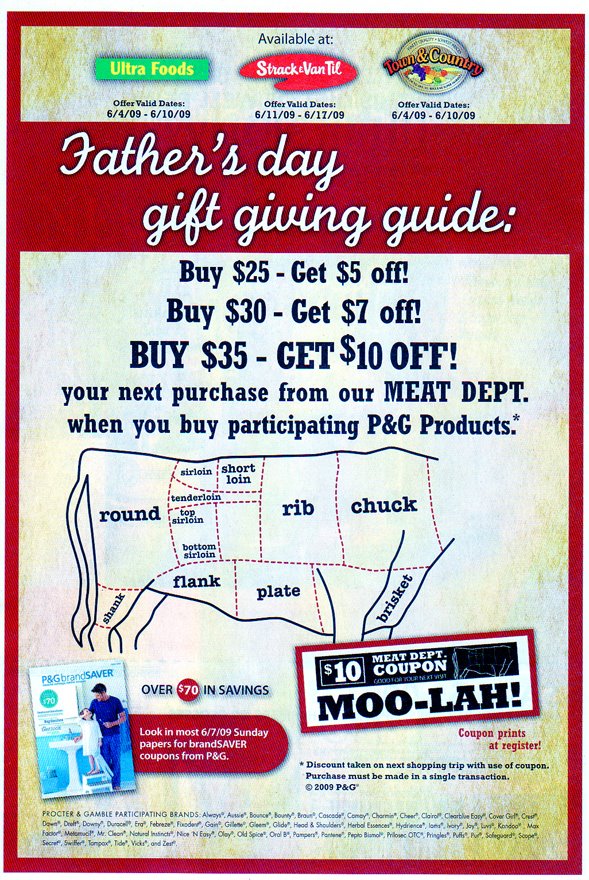

4. …feed their kids fast food (french fries) because, being overwhelmed, she doesn’t have time to feed them what she’d thinks they should eat.

5. …have husbands who still take on the masculine jobs but, being white collar workers, no longer have the skill to effectively perform them.

—————————

Lisa Wade is a professor of sociology at Occidental College. You can follow her on Twitter and Facebook.