Yep. Economics majors are more anti-social than non-econ majors. And taking econ classes also makes people more anti-social than they were before. It turns out, there’s quite a bit of research on this, nicely summarized here. Econ majors are less likely to share, less generous to the needy, and more likely to cheat, lie, and steal.

Yep. Economics majors are more anti-social than non-econ majors. And taking econ classes also makes people more anti-social than they were before. It turns out, there’s quite a bit of research on this, nicely summarized here. Econ majors are less likely to share, less generous to the needy, and more likely to cheat, lie, and steal.

In one study, for example, economists Yoram Bauman and Elaina Rose noted the consistent finding that econ majors were less generous and asked whether the effect was do to selection (people who are anti-social choose to take econ classes) or indoctrination (taking econ classes makes one more anti-social). They found that both play a role.

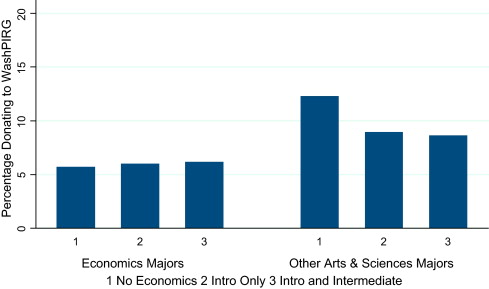

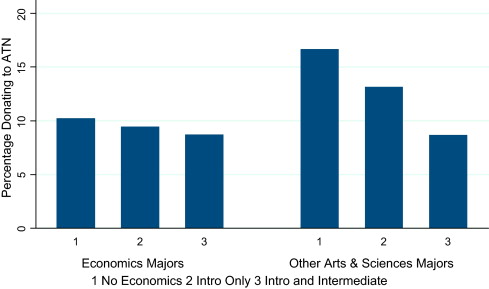

Students at their institution — University of Washington — were asked at registration each semester if they’d like to donate to WashPIRG (a left-leaning public interest group) and ATN (a non-partisan group that lobbies to reduce tuition rates). Bauman and Elaina crunched the data along with students’ chosen majors and classes. They found that econ majors were less likely to donate to either cause (the selection hypothesis) and that non-econ majors who had taken econ classes were less likely to donate than non-majors who hadn’t (the indoctrination hypothesis).

What should we make of these findings?

Sociologist Amitai Etzioni takes a stab at an answer. He argues that neoclassical economics isn’t a problem in itself. Instead, the problem may be that there are no “balancing” classes, ones that present a different kind of economics. In other part of the academy, he argues — specifying social philosophy, political science, and sociology– there is “a great variety of approaches are advanced, thereby leaving students with a consolidated debasing exposure and a cacophony of conflicting pro-social views.”

Being exposed to a variety of views, including ones that question the premises of neoclassical economics, may be one way to make economists more honest and kind. And doing so isn’t just about sticking one to econ, it’s an issue of grave seriousness, as the criminal and immoral behavior of our financial leaders is exactly what triggered a Great Recession once… and could again.

Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.