According to a 2008 market research study, 72% of yoga practitioners in the U.S. are women; 71% are college educated and 27% have postgraduate degrees; and 44% have annual incomes of $75,000 or more. Yoga practitioners, then, do not reflect the general population.

So how inclusive is yoga? A collection of covers from the magazine Yoga Journal, spanning the years 1975 to 2010, sent in by Janet T., gives us a clue.

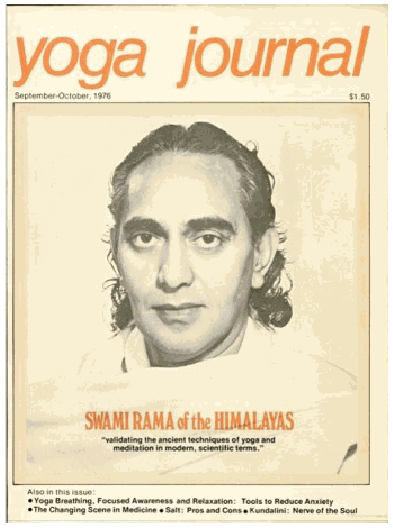

As she points out, the historical progression of covers illustrates how the magazine started out with explicit connections to India and traditional yogis (below) and gradually moved towards featuring (and thus creating) western yoga superstars.

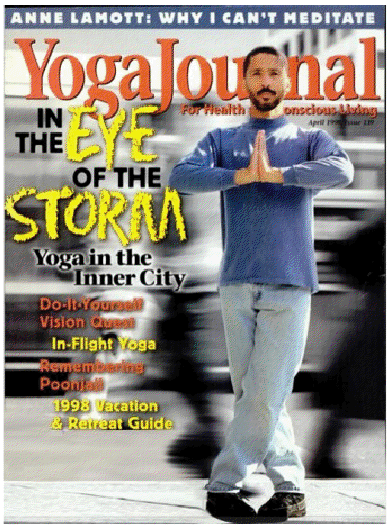

Of the 186 Yoga Journal covers that include a photograph (not an illustration) 78% show only white people. Though a 1997 issue with a story on “yoga in the inner-city” features a man of color:

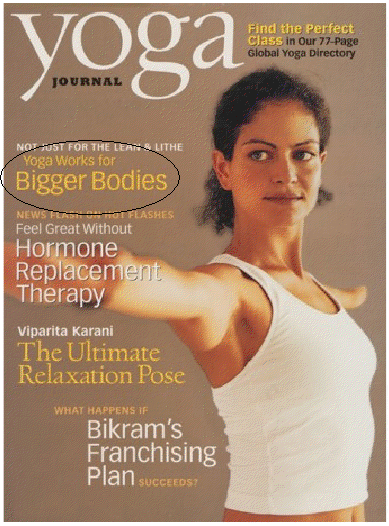

66% of single-person photos are of a woman. At least two covers include a story on yoga for people who aren’t necessarily young, thin, and able-bodied, but show a photograph women who are.

Although the feminization of yoga has been noted (and conversely, the need to masculinize yoga in order to appeal to men), it is rarely acknowledged that while women make up the majority of yoga practitioners, studio owners are more likely to be men. Moreover, yoga superstars, such as Bikram Choudhury (the creator of the Bikram style of yoga practiced in a heated room), with incomes in the multi-millions, are overwhelmingly men.

In addition, while most yoga practitioners are female, the language of yoga is male, and assumes a gender-conforming (and often athletic and thin) body. Some bloggers have called attention to raced, classed, gendered, sizist, and trans–phobic practices in American yoga culture that can be alienating and discouraging to current or would-be yogis, thus denying the potentially therapeutic elements of yoga to much of the U.S. population. For example, the costs associated with yoga practice (classes, equipment, etc.) make it out of reach for most low-income people, while the gendered way that yoga philosophy understands the human body can make it uncomfortable for some transgender folks.

So, through the past 35 years of Yoga Journal covers, we can see how the representation of yoga in America both creates and reinforces a symbolic understanding of a practice intended for a very particular audience.

——————————

Christie Barcelos is a doctoral student in Public Health at the University of Massachusetts who rarely sees anyone who looks like her in yoga class.

If you would like to write a post for Sociological Images, please see our Guidelines for Guest Bloggers.