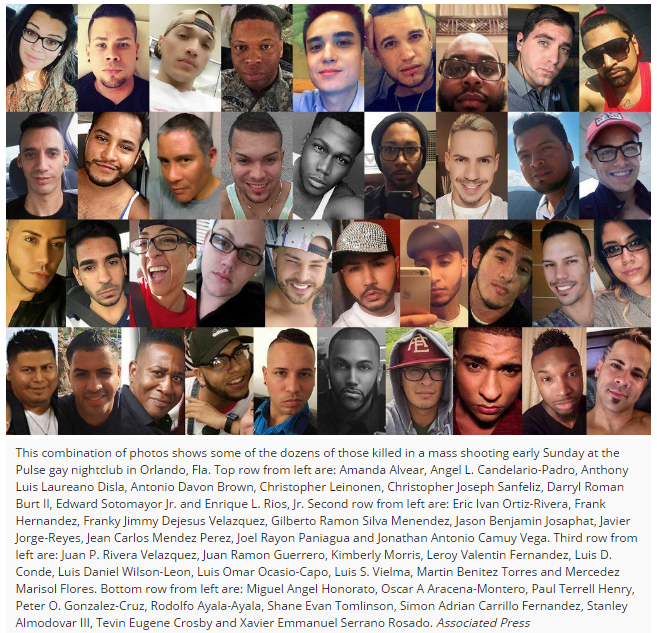

It was “Latino night” at a gay club. When the story finally broke, that’s all I heard. Orlando’s tragedy at the Pulse puts Latina/o, Latin American, Afro-Latinos, and Puerto Ricans and other Caribbean LGBT people front and center. Otherness mounts Otherness, even in the Whitewashing of the ethno-racial background of those killed by the media, and the seemingly compassionate expressions of love by religious folk. The excess of difference—to be Black or Brown (or to be both) and to be gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender (or queer, as some of us see ourselves) serves to shock, through difference, how news are reported. Difference – the very basis of feminist and ethnic politics in the 20th century – has been co-opted and ignored, sanitized even, to attempt to reach a level of a so-called “humanity” that is not accomplishable. We know this, but we don’t talk about it.

It was “Latino night” at a gay club. When the story finally broke, that’s all I heard. Orlando’s tragedy at the Pulse puts Latina/o, Latin American, Afro-Latinos, and Puerto Ricans and other Caribbean LGBT people front and center. Otherness mounts Otherness, even in the Whitewashing of the ethno-racial background of those killed by the media, and the seemingly compassionate expressions of love by religious folk. The excess of difference—to be Black or Brown (or to be both) and to be gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender (or queer, as some of us see ourselves) serves to shock, through difference, how news are reported. Difference – the very basis of feminist and ethnic politics in the 20th century – has been co-opted and ignored, sanitized even, to attempt to reach a level of a so-called “humanity” that is not accomplishable. We know this, but we don’t talk about it.

.

Don’t get me wrong: empathy is essential for most social codes of order to functionally sustain any given society. To pay one’s respects for others’ losses, however, does not mean that we think of those lost as equals. Liberal people demanding that sexuality be less important in the news (and thus removed from the coverage) is an inherent violence toward those who partied together because there was real love among them, in that club, for who they were – and are. Religious righters may spread hate while trying to give the illusion of compassion, but they do so in a clear hierarchical, paternalistic way – that is hypocrisy, and we must call it out every chance we get. But this goes beyond liberal notions and conservative hypocrisy – even while Anderson Cooper wept when reading the list of those killed, he knows the distance between himself and many of those at the club is enough to build a classed, raced, and social wall between them. Clearly, empathy is not enough.

To be Latina/o in the US – increasingly another Latin American country, again – is to breathe in hate, to face retaliation, to be questioned at every turn about our allegiances, tested on our sense of citizenship, pushed in our capacity to love the nation and thus hate “like the rest” (a testament to the masculinity of the nation). At a minimum, to be Latina/o guarantees one to be looked at oddly, as if one was out of place, misplaced, inappropriately placed. Simply by being, Latinas/os rupture the logics of normalcy in USAmerica. To be Latina/o and LGBT is to disrupt the logics of racial formation, of racial purity, of the Black and White binary still ruling this country – all while de-gendering and performing an excess (of not only gender, but sexuality) that overflows and overwhelms “America.” In being Latino and queer, some of us aim to be misfits that disrupt a normalcy of regulatory ways of being.

A break between queer and América erupted this past weekend – in Orlando, a city filled with many Latin Americans; a city that, like many others, depends on the backs of Brown folk to get the work done. Put another way, Orlando’s tragedy created a bridge between different countries and newer readings of queerness – Orlando as in an extension of Latin América here. Queer-Orlando-América is an extension of so many Latin American cities as sites of contention, where to be LGBT is both celebrated and chastised – no more, or less, than homophobia in the US.

Enough has been said about how the Pulse is a place where people of color who desired others like themselves, or are trans, go to dance their fears away, and dream on hope for a better day. Too little has been said about the structural conditions faced by these Puerto Ricans, these immigrants, these mixed raced queer folks – some of whom were vacationing, many of whom lived in Florida. Many were struggling for a better (financial, social, political – all of the above) life. Assumptions have also been made about their good fortune as well. Do not assume that they left their countries seeking freedom – for many who might have experienced homophobia back home, still do here; though they have added racism to their everyday lived experience. Of course, there are contradictions on that side of queer-Orlando-América, too; yet same sex marriage was achieved in half a dozen countries before the US granted it a year ago. This is the world upside down, you say, since these advances – this progress – should have happened in the US first.Wake up. América is in you and you are no longer “America” but América.

You see, this is how we become queer-Orlando-América: we make it a verb, an action. It emerges where the tongues twist, where code switching (in Spanish/English/Spanglish) is like a saché-ing on the dance floor, where gender and race are blurry and yet so clear, where Whiteness isn’t front and center – in fact it becomes awkward in this sea of racial, gendered, and sexual differences. This queer-Orlando-América (a place neither “here,” nor “there,” where belonging is something you carry with you, in you, and may activate on some dance floor given the right people, even strangers, and real love – especially from strangers) was triggered – was released – by violence. But not a new violence, certainly not a Muslim-led violence. Violence accumulated over violence – historically, ethnically, specific to transgender people, to Brown people, to effeminate male-bodied people, to the power of femininity in male and female bodies, to immigrants, to the colonized who speak up, to the Spanglish that ruptures “appropriateness,” to the language of the border. And in spite of this, queer-Orlando-América has erupted. It is not going down to the bottom of the earth. You see us. It was, after all, “Latino night” at a gay club. You can no longer ignore us.

As the week advanced, and fathers’ day passed us by, I have already noticed the reordering of the news, a staged dismissal so common in media outlets. Those queer and Brown must continue to raise this as an issue, to not let the comfort of your organized, White hetero-lives go back to normal. You never left that comfort, you just thought about “those” killed. But it was “Latino night” at a gay club. I do not have that luxury. I carry its weight with me. Now the lives of those who are queer and Latina/o have changed – fueled with surveillance and concerns, never taking a temporary safe space for granted. Queer-Orlando-América is thus a “here and now” that has changed the contours of what “queer” and “America” were and are. Queer has now become less White – in your imaginary (we were always here). América now has an accent (it always had it – you just failed to notice). Violence in Orlando did this. It broke your understanding of a norm and showed you there is much more than the straight and narrow, or the Black and White “America” that is segmented into neatly organized compartments. In that, Orlando queers much more than those LGBT Latinas/os at the club. Orlando is the rupture that bridges a queer Brown United States with a Latin America that was always already “inside” the US – one that never left, one which was invaded and conquered. Think Aztlán. Think Borinquen. Think The Mission in San Francisco. Or Jackson Heights, in NYC. Or the DC metro area’s Latino neighborhoods. That is not going away. It is multiplying.

I may be a queer Latino man at home, at the University, at the store, and at the club. That does not mean that the layered account of my life gets acknowledged (nor celebrated) in many of those sites – in fact, it gets fractured in the service of others’ understandings of difference (be it “diversity,” “multiculturalism” or “inclusion”). But it sure comes together on the dance floor at a club with a boom-boom that caters to every fiber of my being. It is encompassing. It covers us. It is relational. It moves us – together. So, even if I only go out once a year, I refuse to be afraid to go out and celebrate life. Too many before me have danced and danced and danced (including those who danced to the afterlife because of AIDS, hatred, and homophobia), and I will celebrate them dancing – one night at a time.

We are not going away – in fact, a type of queer-Orlando-América is coming near you, if it hasn’t arrived already, if it wasn’t there already—before you claimed that space. No words of empathy will be enough to negotiate your hypocrisy, to whitewash our heritage, or make me, and us, go away. If anything, this sort of tragedy ignites community, it forces us to have conversations long overdue, it serves as a mirror showing how little we really have in common with each other in “America” – and the only way to make that OK is to be OK with the discomfort difference makes you experience, instead of erasing it.

We must never forget that it was “Latino night” at a gay club. That is how I will remember it.

Salvador Vidal-Ortiz, PhD, is associate professor of sociology at American University; he also teaches for their Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies program. He coedited The Sexuality of Migration: Border Crossings and Mexican Immigrant Men and Queer Brown Voices: Personal Narratives of Latina/o LGBT Activism. He wrote this post, originally, for Feminist Reflections.