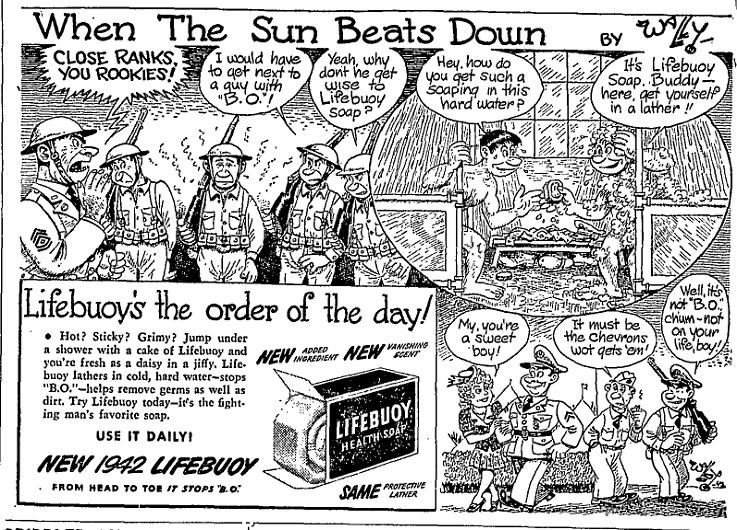

This 1942 ad for Lifebuoy soap is a great example of shifts in collective cultural awareness of homosexuality. From a contemporary U.S. perspective, where most of us have heard homophobic jokes about not dropping the soap in the shower, two men showering together (even or especially in a military context) and using language like “hard” and “get yourself in a lather” is undeniably a humorous reference to gay men.

I think, however, that this was not at all the intention in 1942, where the possibility of men’s sexual attraction to other men wasn’t so prominent of a cultural trope. It simply wasn’t on people’s minds as it is today. Accordingly, the ad seems to be a simple illustrated recommendation, complete with a nice heterosexual prize at the end.

From Vintage Ads.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.