In early 20th century America, eugenics was promoted as a new way to scientifically shape the human race. The idea was to change the human population for the better through selective breeding and sterilization. As you can imagine, this led to serious abuses. People of color, the poor, and those deemed otherwise unfit for reproduction were disproportionately targeted, and usually the sterilization was accomplished by targeting women’s bodies in particular.

One interesting facet of the effort to promote eugenics is the language used, or the framing of the issue. Indeed, just last week I introduced my students to the notion of “Birthright.” The term birthright suggested that all children have the right to be born into a sound mind and body. Why was it important to sterilize individuals deemed morally, culturally, or biologically inferior? Why, we must do it for the children, of course!

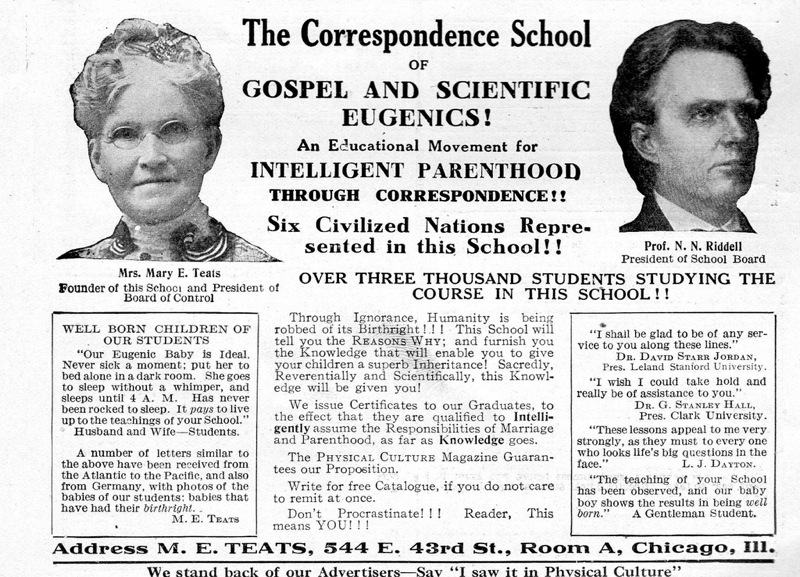

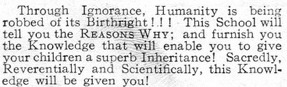

I was reminded of the idea of children having such a birthright by a vintage ad (posted at, predictably, Vintage Ads). The ad is for a school designed to improve the future of the human race by improving parenting. The school would, therefore, teach parents how to engage in civilized “intelligent” “parenthood.” The idea that such parenting can be taught points to the way that eugenics evolved from a biological to a cultural basis. And in several places you see the term “birthright” (excerpted below).

Excerpts:

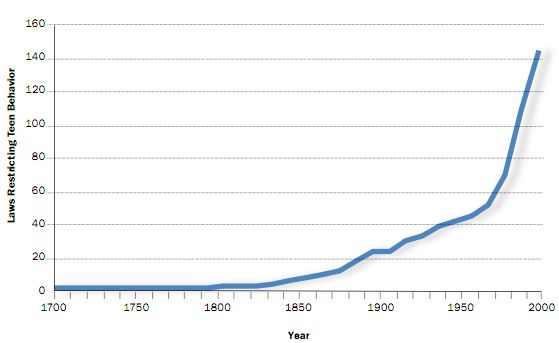

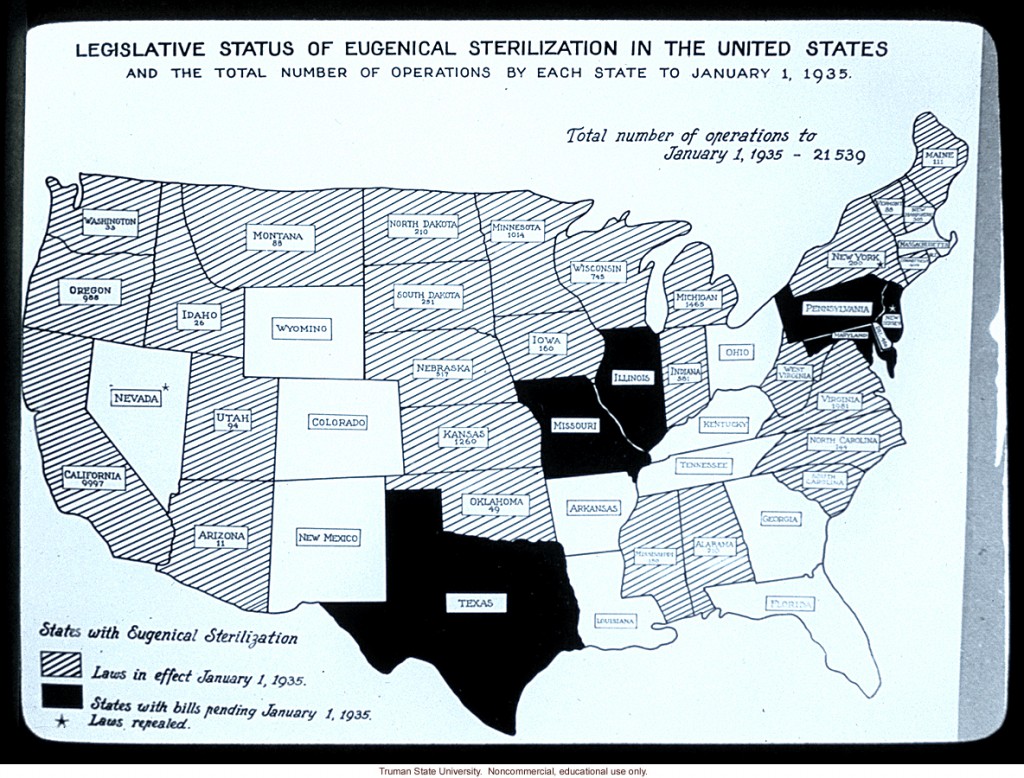

For a time, pro-sterilization laws were very popular. The U.S. map below, for example, shows which states had pro-sterilization laws in 1935 (striped) and states with laws pending (black). As you can see, most of the United States was on board at this time. Later, condemnation of the practices in Nazi Germany would take the blush off of the eugenics rose.

(source)

(source)

For a wonderful book on the history of eugenics, read Wendy Kline’s Building a Better Race: Gender, Sexuality, and Eugenics from the Turn of the Century to the Baby Boom.

For more on eugenics and sterilization, see our post with additional pro-eugenics propaganda and two contemporary examples of coercive sterilization campaigns by your health insurance carrier and politician who’ll pay the “unfit” to get tied.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.