Wired has posted a set of photos by Richard Ross highlighting the harsh reality of life in juvenile detention centers — locations where about 60,000 kids reside each night throughout the U.S. According to the article,

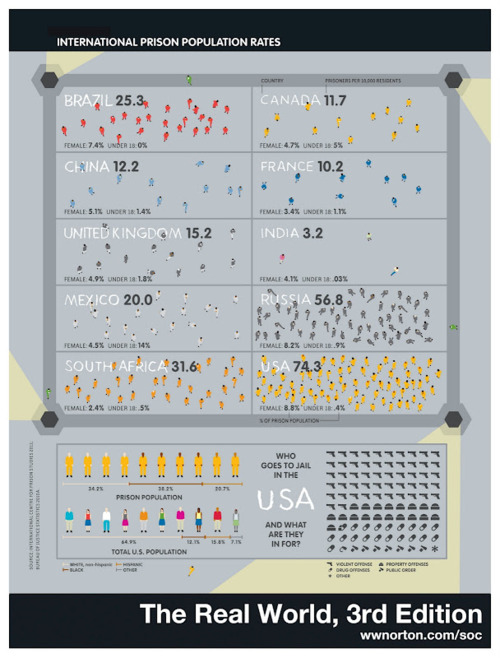

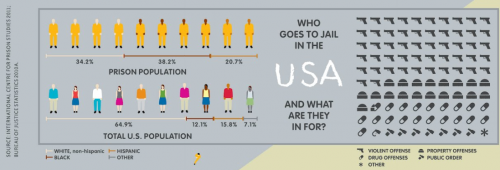

The U.S. locks up children at more than six times the rate of all other developed nations. The over 60,000 average daily juvenile lockups, a figure estimated by the Annie E. Casey Foundation (AECF), are also disproportionately young people of color. With an average cost of $80,000 per year to lock up a child, the U.S. spends more than $5 billion annually on youth detention.

The images are at Wired, and you can read more about the project, Juvenile-in-Justice, including a schedule of shows, at Ross’s website. His photos also appear in the Annie E. Casey Foundation report No Place for Kids.

You might also want to check out our previous posts on treatment of prisoners during Hurricane Katrina and overcrowding in California prisons.

And thanks to Karl for the tip about the article!

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.