New York City’s stop-and-frisk policy has gotten intensified scrutiny recently. A stop and frisk refers to police officers stopping and searching individuals who are out in public. These stops don’t require a warrant; the police officer has to have reasonable cause to believe the person is engaged in criminal activity.

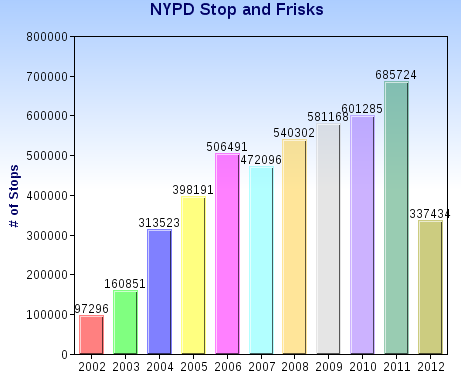

Critics point out that these stops are incredibly inefficient, and that relying on cops’ evaluations of who is suspicious opens the door to widespread racial profiling. The New York Civil Liberties Union analyzed the NYPD’s own data, which they are required to record about all stops. Over the past decade, literally millions of people have been the targets of stop-and-frisks, with steady growth in the use of the program. I made a chart of the data from 2002 through the first 6 months of 2012:

Yet all these stops have led to little discovery of actual crime. Overall, about 87-89% of stops lead to no evidence of wrong-doing.

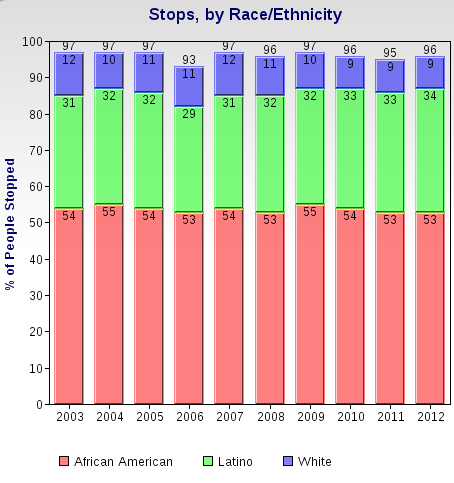

These stops have also disproportionately affected minorities. Here’s a breakdown by race/ethnicity, based on the NYPD data:

You can read more about the data on stop-and-frisks at the NYCLU website.

The Nation recently posted a video that discusses the impacts of stop-and-frisk on the lives of those targeted and on perceptions of the police, as well as police officers discussing the pressure to complete stop-and-frisks. The clip includes an audio recording that a 17-year-old made when he was being targeted for a stop-and-frisk after having just been stopped a couple of blocks earlier. As the video makes clear, these stops are about more than an inconvenience in citizens’ lives; they involve real harassment and fear of violence for those who find themselves the target of police suspicions: