The recent controversial arrests at a Philadelphia Starbucks, where a manager called the police on two Black men who had only been in the store a few minutes, are an important reminder that bias in the American criminal justice system creates both large scale, dramatic disparities and little, everyday inequalities. Research shows that common misdemeanors are a big part of this, because fines and fees can pile up on people who are more likely to be policed for small infractions.

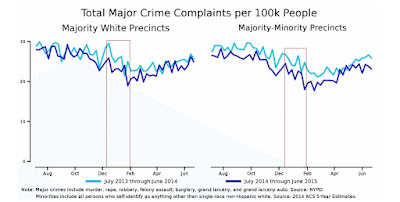

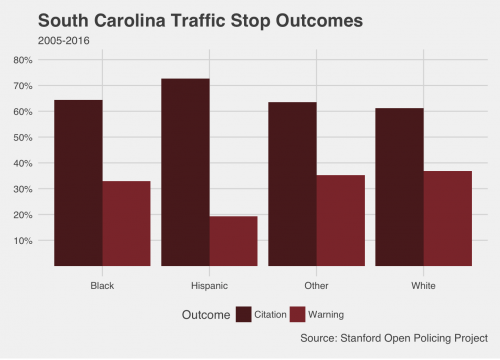

A great example is the common traffic ticket. Some drivers who get pulled over get a ticket, while others get let off with a warning. Does that discretion shake out differently depending on the driver’s race? The Stanford Open Policing Project has collected data on over 60 million traffic stops, and a working paper from the project finds that Black and Hispanic drivers are more likely to be ticketed or searched at a stop than white drivers.

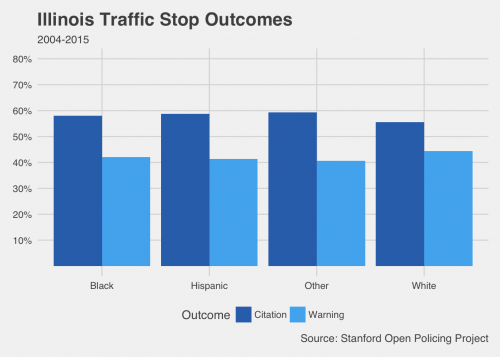

To see some of these patterns in a quick exercise, we pulled the project’s data on over four million stop records from Illinois and over eight million records from South Carolina. These charts are only a first look—we split the recorded outcomes of stops across the different codes for driver race available in the data and didn’t control for additional factors. However, they give a troubling basic picture about who gets a ticket and who drives away with a warning.

These charts show more dramatic disparities in South Carolina, but a larger proportion of white drivers who were stopped got off with warnings (and fewer got tickets) in Illinois as well. In fact, with millions of observations in each data set, differences of even a few percentage points can represent hundreds, even thousands of drivers. Think about how much revenue those tickets bring in, and who has to pay them. In the criminal justice system, the little things can add up quickly.