Cross-posted at Love Isn’t Enough.

Ann DuCille, in her book Skin Trade, takes two issues with “ethnic” Barbies.

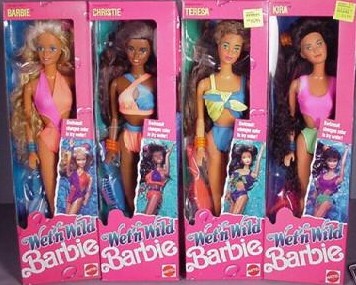

First, she takes issue with the fact that “ethnic” Barbies are made from the same mold as “real” Barbies (though sometimes with different paint on their faces). This reifies a white standard of beauty as THE standard of beauty. Black women are beautiful only insofar as they look like white women (see also this post). DuCille writes:

…today Barbie dolls come in a rainbow coalition of colors, races, ethnicities, and nationalities, [but] all of those dolls look remarkably like the stereotypical white Barbie, modified only by a dash of color and a change of clothes.

Consider:

But, second, DuCille also takes takes issue with the idea that Mattell would try to make ethnic Barbies more “authentic.” Trying to agree on one ideal form for a racial or ethnic group is no more freeing than trying to get everyone to accord to one ideal based in whiteness. DuCille writes:

…it reifies race. You can’t make an ‘authentic’ Black, Hispanic, Asian, or white doll. You just can’t. It will always be artificially constraining…

And also:

Just what are we saying when we claim that a doll does or does not look… black? How does black look? …What would make a doll look authentically African American or realistically Nigerian or Jamaican? What prescriptive ideals of blackness are inscribed in such claims of authenticity? …The fact that skin color and other ‘ethnic features’ …are used by toymakers to denote blackness raises critical questions about how we manufacture difference.

Indeed, difference is, literally, manufactured through the production of “ethnic” Barbies and this is done, largely, for a white audience.

To be profitable, racial and cultural diversity… must be reducible to such common, reproducible denominators as color and costume.

The majority of American Barbie buyers are only interested in “ethnicity” so long as it is made into cute and harmless variety. This reminds us that, when toy makers (and others) manufacture difference, they are doing so for money. DuCille writes:

…capitalism has appropriated what it sees as certain signifiers of blackness and made them marketable… Mattel… mass market[s] the discursively familiar–by reproducing stereotyped forms and visible signs of racial and ethnic difference.

Consider:

Black Barbie and Hispanic Barbie, 1980

Oriental Barbie, date unknown

Diwali Barbie (India)

Hula Honey Barbie

Kwanzaa Barbie

Radiant Rose Ethnic Barbie, 1996

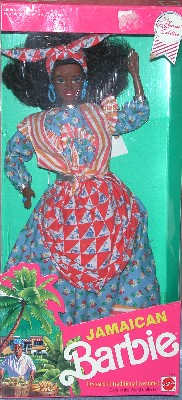

There are many reasons to find this problematic. DuCille turns to the Jamaican Barbie as an example.

The back of Jamaican Barbie’s box tells us:

How-you-du (Hello) from the land of Jamaica, a tropical paradise known for its exotic fruit, sugar cane, breath-taking beaches, and reggae beat! …most Jamaicans have ancestors from Africa, so even though our official language is English, we speak patois, a kind of ‘Jamaica Talk,’ filled with English and African words. For example, when I’m filled with boonoonoonoos, I’m filled with much happiness!

Notice how Jamaica is reduced to cutesy things like exotic fruit and sugar cane and Jamaican people are characterized as happy-go-lucky and barely literate while the history of colonialism is completely erased.

So DuCille doesn’t like it when Black Barbies, for example, look like White Barbies and she doesn’t like it when Black Barbies look like Black Barbies either. What’s the solution? The solution simply may not lie in representation, so much as in actually correcting the injustice in which representation occurs.

(Images found here, here, here, here, here, and here.)

For a related post on race and friendship, see here.