This excellent documentary documents the powerful interests behind Disney and criticizes the extent to which young American children’s childhoods are influenced by the company. The comments on the messages behind Beauty and the Beast are particularly troubling.

children/youth

A Cracked article compiled their candidates for the Nine Most Racist Disney Characters. Select stolen clips and liberal quoting below:

American Indians in Peter Pan:

Why do Native Americans ask you “how?” According to the song, it’s because the Native American always thirsts for knowledge. OK, that’s not so bad, we guess. What gives the Native Americans their distinctive coloring? The song says a long time ago, a Native American blushed red when he kissed a girl, and, as science dictates, it’s been part of their race’s genetic make up since. You see, there had to be some kind of event to change their skin from the normal, human color of “white.”

The bad guys in Alladin:

“Where they cut off your ear if they don’t like your face” is the offending line, which was changed on the DVD to the much less provocative “Where it’s flat and immense and the heat is intense.”

In a city full of Arabic men and women, where the hell does a midwestern-accented, white piece of cornbread like Aladdin come from? Here he is next to the more, um, ethnic looking villain, Jafar.

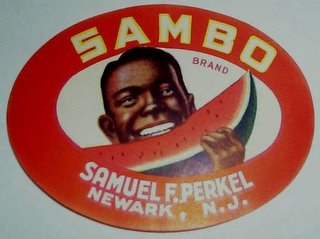

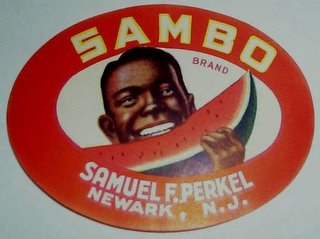

NEW: Miguel (of El Forastero) sent in a post from El Blog Ausente that compares an image of Goofy, a character generally portrayed as sort of dumb and lazy, to a traditional Sambo-type image:

The post suggests that Goofy is a racial archetype, built on stereotypical African American caricatures. I can’t remember ever seeing anything that suggested this, but that doesn’t mean much, and I certainly don’t put it past Disney to do so. Does anyone know of any other examples of Goofy supposedly being based on African American stereotypes? On the other hand, is it possible to depict a character eating watermelon in an exuberant manner without drawing on those racist images? When I look at the image of Goofy above, I have to say…that’s pretty much what it looks like when my (mostly White) family cuts a watermelon open out on the picnic table in the summer and everybody gets a piece and they all have ridiculous looks on their faces as they dribble juice all down themselves eating big chunks (I say “they” because I’m a weirdo who doesn’t really care for watermelon, so I rarely eat any, and even then only if I can put salt on it). I’m fairly certain that I couldn’t put up a photo of my family eating watermelon like that without it seeming, to many people, to draw on the Sambo-type imagery. It brings up some interesting thoughts about cultural and historical contexts, and how and in what circumstances you can (or can’t) escape them, regardless of your intent.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

(Image found here.)

(Image found here.)

Ballgame at Feminist Critics writes:

The assertion, “children do better with parents together” could mean a number of different things, so let’s go through the possible ways the statement could be interpreted:

The notion that “Children ALWAYS do better with parents together” is almost certainly false. If one of the parents is abusive, it seems pretty non-controversial to assume that the kids would be better off with the non-abusive parent alone.

The notion that “Children SOMETIMES do better with parents together” is almost certainly true, but so banal and useless an observation that it’s not worth the expense of a billboard or worth discussing at any length.

That leaves “Children GENERALLY do better with parents together.” This, itself, has two entirely different meanings which are easily confused. Take 100 couples with children. Of those couples, 75 are (at the moment) happily married, while 25 have marital difficulties — some severe — and are on the brink of divorce. Let’s say 20 of the 25 couples actually go through with the divorce.

The notion that “Children GENERALLY do better with parents together” could be taken to mean that, out of the 100 families described above, children from the 80 non-divorcing families end up being mentally and emotionally healthier (as a group) than the children from the 20 divorcing families. That is very easy to believe. Indeed, there are any number of studies that show this, and these are the studies that are typically trotted out to misleadingly imply that divorce hurts children. In fact it’s just another rather banal observation that children from happy families do better than children from emotionally fraught ones, and hardly worth the price of a billboard. It’s almost like saying, “People with money are less likely to have difficulties making ends meet.”

But the other meaning of “Children GENERALLY do better with parents together” is quite different: namely, that the children in the 20 divorcing families would have been better off if those parents hadn’t gotten divorced. THAT notion is purely speculative as far as I know.

Via Alas.

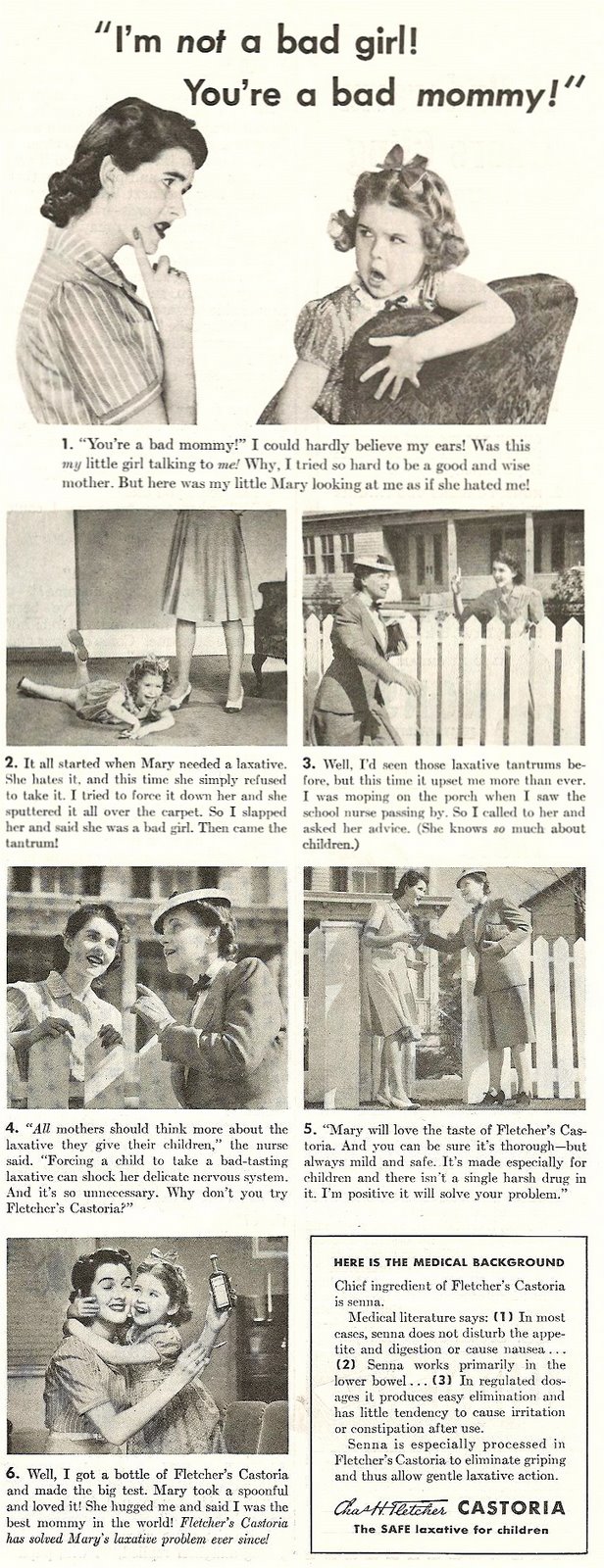

Ben O. sent us this 1941 ad for Fletcher’s Castoria (found at I’m Learning to Share), in which mothers are warned (by a bratty kid) that they better give their children Fletcher’s laxatives or their children will hate them:

Text from section 2:

It all started when Mary needed a laxative. She hates it, and this time she simply refused to take it. I tried to force it down her and she splattered it all over the carpet. So I slapped her and said she was a bad girl. Then came the tantrum!

I’d say slapping her daughter is more of an indication of what type of mother she is than which laxatives she chooses, but whatever. Apparently the company liked to use corporal punishment in its ads; here are some more examples (both found at Corpun). In this first one, we learn that even parents who don’t believe in spanking may be driven to it if they use the wrong laxative (in section 2, she gives him an “unmerciful spanking”):

Text from sections 1 and 2:

I don’t believe in spanking children. But darn it all, sometimes a youngster can sure drive a grownup wild. Like mine did me–yesterday. It all started innocently when Billy wouldn’t take his laxative. At first I tried coaxing. But that didn’t work. Then when I started to force it on him, he sent the spoon flying out of my hand. So I lost my temper and gave him an unmerciful spanking.

From section 1:

Whenever Tommy gets a spanking, our whole family is upset. Big Tom hates to do it and mopes for hours afterward. And Tommy’s little nervous system gets so upset he can’t eat. So last Friday I decided to put an end to spankings…

Fletcher’s Castoria: the way to digestive and family harmony. Without it, you might end up slapping the kids around (though I have to say, that girl at the top would probably test to the utmost my opposition to violence).

Just a question: I’m not a parent, but I don’t hear my friends talking about giving their kids laxatives all the time, and I don’t remember being forced to take them as a kid (though I do remember us forcing a horse to drink a lot of castor oil once). Was this just a health fad at the time that people thought kids needed that has fallen out of favor? Did kids in the ’40s have some unique digestive problems we’ve, um, eliminated since then? Or do my friends’ kids go around constipated all the time because they don’t know to make them take senna laxatives?

Thanks again, Ben!

NEW! Sarah N. sent us another example of an add that implies laxatives lead to happier moms and better family lives:

Part of the text:

“My mum loves me now. I can tell because her hands are gentler…her voice is sweeter…and her kisses are softer. I know know what I did. But all of a sudden she just started loving me!”

Linda, dear, you didn’t do anything. It was Mum’s chemist. He gave her Bile Beans…

Aaron B. sent in this 1947 video clip (found here), titled “Are You Popular?”:

Notice the caution to women: if you go “parking with all the boys,” you might think you’re popular, but you’ll ultimately find yourself ostracized and friendless. To be really popular, you need to be well-dressed, have the respect of girls at school, and carefully guard your reputation.

Thanks, Aaron!

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.

In a comment a while back, Elena pointed out that Diego Velázquez’s painting “Infante Felipe Próspero” (from 1659) provides a good example of how pink was acceptable for males to wear…as were, in some cases, dresses, which the young prince is wearing:

Elena says,

…until the late 1700s little boys would wear dresses or petticoats for as long as they could until they could dress as miniature adults…This was mainly for ease of bodily functions.

Of course, today most parents would be appalled at the idea of dressing toddler boys in dresses–dresses with frills and ribbons, at that.

The painting “Pope Innocent X,” also by Velázquez (1650) shows the Pope in light pink clothing:

Both images found at the National Gallery’s Velázquez page.

You might also check out Kent State University Museum’s Centuries of Childhood exhibit for examples of how children’s clothing has changed over time.

Thanks for the tip, Elena!

Speaking as a 30-year-old who still cherishes a threadbare, 29-year-old specimen, I can personally testify that teddy bears are objects highly charged with affect in modern U.S. bourgeois white society. Along with blankets, stuffed animals are frequently given to young children to play with. Many times, children grow attached to their animals and blankets, naming them, talking to them, sleeping with them and taking them everywhere.

In 1951, Donald Winnicott called such stuffed animals and security blankets “transitional objects.” I’m probably grossly simplifying this, but he posited that transitional objects occupy an important position in children’s emotional lives as mechanisms by which they soothe themselves as they differentiate their identities from those of their parents. Parenting advice emphasizes that transitional objects are part of a “normal and healthy phase of development” and even a “good thing” that parents may want to voluntarily introduce to anxious children.

In short, modern middle-class bourgeois white society associates teddy bears with a deep emotional connection between people. Teddy bears symbolize comfort and a nurturing parent-child bond. To many, they are images of love.

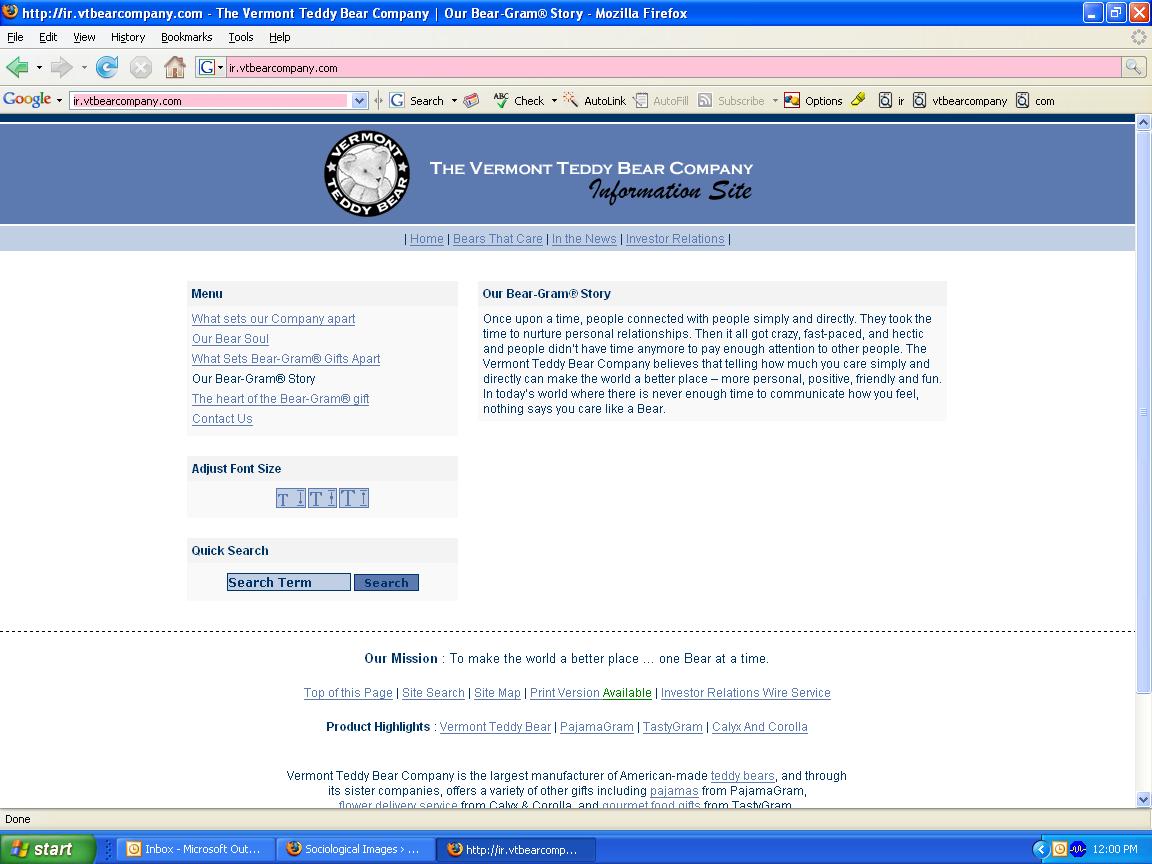

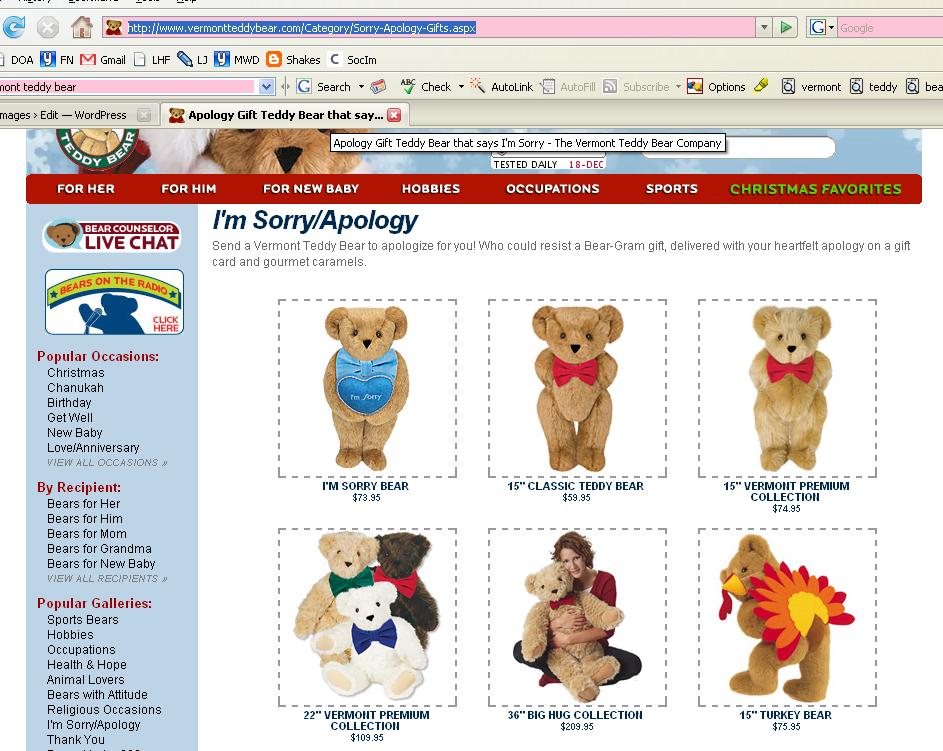

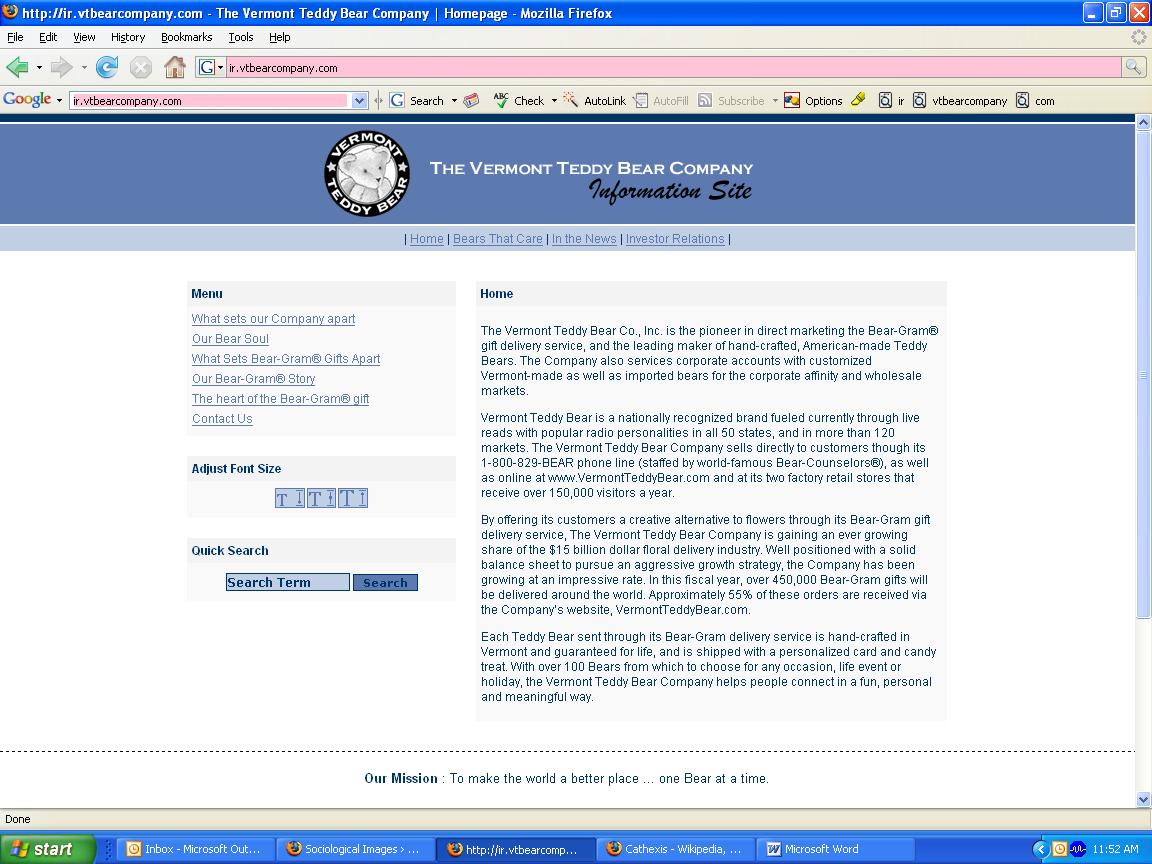

Over on its Web site for investors, Vermont Teddy Bear literally capitalizes on the “bears=love” connotations by couching its business in terms that suggest relationships and closeness. In this screenshot from the investor relations home page, for example, you can see that the over-the-phone sales staff are called “Bear Counselors,” suggesting that they give advice and mentoring about relationships.

On the page entitled “Our Bear-Gram Story,” Vermont Teddy Bear positions its product as equivalent to the emotional work of creating and sustaining authentic relationships. The “story” says:

Once upon a time, people connected with people simply and directly. They took the time to nurture personal relationships. Then it all got crazy, fast-paced, and hectic and people didn’t have time anymore to pay enough attention to other people.

Of course, the thought that it was so good back in Ye Olde Non-Hectick Tymes is problematic, but so is the thought that teddy bears will suffice instead of “pay[ing] attention to other people.” Why expend all that effort relating to someone when you can just toss him or her a teddy bear instead?

On the company’s site for customers, the same association between the toys and love appears, as evidenced by this banner proclaiming the teddy bears as “heartfelt,” an adjective usually used to describe significant declarations of sentiment:

For occasions that require difficult, emotionally draining “relationship work,” there’s even a whole category of “I’m Sorry/Apology” bears available to send.

The I’m Sorry Bear comes with the following descriptive copy:

Whether you’ve broken their heart or their favorite coffee mug this Bear has got it covered. Holding a light blue pillow embroidered with the an “I’m Sorry” message and wearing a matching light blue bowtie, this Bear is a sure way to earn their forgiveness.

Ah, what price forgiveness?

Well, it’s $73.95. [Shipping and handling excluded. Insurance and rush orders extra. Please ask for international rates. Customs taxes may apply outside U.S. Order early to insure delivery by Christmas!]

I suppose that Vermont Teddy Bear’s deployment of a stuffed animal to do your emotional work for you is in the same category as ad campaigns for diamonds and credit cards that promise viewers intimacy through purchase of the products. However, Vermont Teddy Bear’s use of the “objects will fulfill you” trope is slipperier in part because a substantial number of potential consumers have experience with teddy bears as transitional objects that did [or still do] make them feel happy and calm.

In an amusing postscript, I grew up in Vermont, where we were kind of expected to support Vermont Teddy Bear Company. But when someone gave my younger brother a Vermont Teddy Bear as a gift, he never touched it. Finding the bear stiff and kind of lumpy, he preferred to drag around smaller and more squishable stuffed animals. No one else in the family was impressed with its cuddlability, not even me, and I was the one who collected stuffed animals to line the edges of my bed every night. The bear is now sitting on my mom’s desk as a display item, having not created an emotional connection at all.

A Cracked article compiled their candidates for the Nine Most Racist Disney Characters. Select stolen clips and liberal quoting below:

American Indians in Peter Pan:

Why do Native Americans ask you “how?” According to the song, it’s because the Native American always thirsts for knowledge. OK, that’s not so bad, we guess. What gives the Native Americans their distinctive coloring? The song says a long time ago, a Native American blushed red when he kissed a girl, and, as science dictates, it’s been part of their race’s genetic make up since. You see, there had to be some kind of event to change their skin from the normal, human color of “white.”

The bad guys in Alladin:

“Where they cut off your ear if they don’t like your face” is the offending line, which was changed on the DVD to the much less provocative “Where it’s flat and immense and the heat is intense.”

In a city full of Arabic men and women, where the hell does a midwestern-accented, white piece of cornbread like Aladdin come from? Here he is next to the more, um, ethnic looking villain, Jafar.

NEW: Miguel (of El Forastero) sent in a post from El Blog Ausente that compares an image of Goofy, a character generally portrayed as sort of dumb and lazy, to a traditional Sambo-type image:

The post suggests that Goofy is a racial archetype, built on stereotypical African American caricatures. I can’t remember ever seeing anything that suggested this, but that doesn’t mean much, and I certainly don’t put it past Disney to do so. Does anyone know of any other examples of Goofy supposedly being based on African American stereotypes? On the other hand, is it possible to depict a character eating watermelon in an exuberant manner without drawing on those racist images? When I look at the image of Goofy above, I have to say…that’s pretty much what it looks like when my (mostly White) family cuts a watermelon open out on the picnic table in the summer and everybody gets a piece and they all have ridiculous looks on their faces as they dribble juice all down themselves eating big chunks (I say “they” because I’m a weirdo who doesn’t really care for watermelon, so I rarely eat any, and even then only if I can put salt on it). I’m fairly certain that I couldn’t put up a photo of my family eating watermelon like that without it seeming, to many people, to draw on the Sambo-type imagery. It brings up some interesting thoughts about cultural and historical contexts, and how and in what circumstances you can (or can’t) escape them, regardless of your intent.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

(Image found here.)

(Image found here.)

Ballgame at Feminist Critics writes:

The assertion, “children do better with parents together” could mean a number of different things, so let’s go through the possible ways the statement could be interpreted:

The notion that “Children ALWAYS do better with parents together” is almost certainly false. If one of the parents is abusive, it seems pretty non-controversial to assume that the kids would be better off with the non-abusive parent alone.

The notion that “Children SOMETIMES do better with parents together” is almost certainly true, but so banal and useless an observation that it’s not worth the expense of a billboard or worth discussing at any length.

That leaves “Children GENERALLY do better with parents together.” This, itself, has two entirely different meanings which are easily confused. Take 100 couples with children. Of those couples, 75 are (at the moment) happily married, while 25 have marital difficulties — some severe — and are on the brink of divorce. Let’s say 20 of the 25 couples actually go through with the divorce.

The notion that “Children GENERALLY do better with parents together” could be taken to mean that, out of the 100 families described above, children from the 80 non-divorcing families end up being mentally and emotionally healthier (as a group) than the children from the 20 divorcing families. That is very easy to believe. Indeed, there are any number of studies that show this, and these are the studies that are typically trotted out to misleadingly imply that divorce hurts children. In fact it’s just another rather banal observation that children from happy families do better than children from emotionally fraught ones, and hardly worth the price of a billboard. It’s almost like saying, “People with money are less likely to have difficulties making ends meet.”

But the other meaning of “Children GENERALLY do better with parents together” is quite different: namely, that the children in the 20 divorcing families would have been better off if those parents hadn’t gotten divorced. THAT notion is purely speculative as far as I know.

Via Alas.

Ben O. sent us this 1941 ad for Fletcher’s Castoria (found at I’m Learning to Share), in which mothers are warned (by a bratty kid) that they better give their children Fletcher’s laxatives or their children will hate them:

Text from section 2:

It all started when Mary needed a laxative. She hates it, and this time she simply refused to take it. I tried to force it down her and she splattered it all over the carpet. So I slapped her and said she was a bad girl. Then came the tantrum!

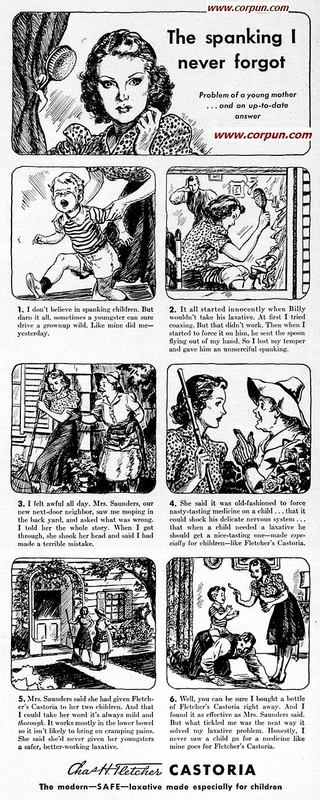

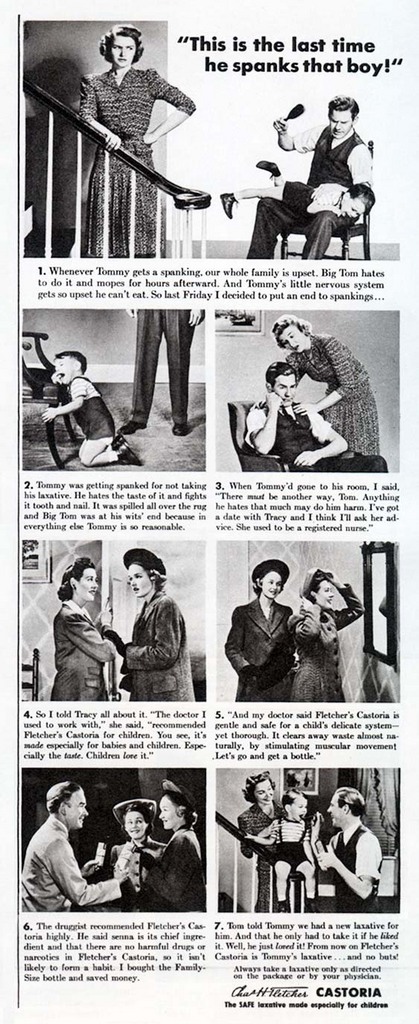

I’d say slapping her daughter is more of an indication of what type of mother she is than which laxatives she chooses, but whatever. Apparently the company liked to use corporal punishment in its ads; here are some more examples (both found at Corpun). In this first one, we learn that even parents who don’t believe in spanking may be driven to it if they use the wrong laxative (in section 2, she gives him an “unmerciful spanking”):

Text from sections 1 and 2:

I don’t believe in spanking children. But darn it all, sometimes a youngster can sure drive a grownup wild. Like mine did me–yesterday. It all started innocently when Billy wouldn’t take his laxative. At first I tried coaxing. But that didn’t work. Then when I started to force it on him, he sent the spoon flying out of my hand. So I lost my temper and gave him an unmerciful spanking.

From section 1:

Whenever Tommy gets a spanking, our whole family is upset. Big Tom hates to do it and mopes for hours afterward. And Tommy’s little nervous system gets so upset he can’t eat. So last Friday I decided to put an end to spankings…

Fletcher’s Castoria: the way to digestive and family harmony. Without it, you might end up slapping the kids around (though I have to say, that girl at the top would probably test to the utmost my opposition to violence).

Just a question: I’m not a parent, but I don’t hear my friends talking about giving their kids laxatives all the time, and I don’t remember being forced to take them as a kid (though I do remember us forcing a horse to drink a lot of castor oil once). Was this just a health fad at the time that people thought kids needed that has fallen out of favor? Did kids in the ’40s have some unique digestive problems we’ve, um, eliminated since then? Or do my friends’ kids go around constipated all the time because they don’t know to make them take senna laxatives?

Thanks again, Ben!

NEW! Sarah N. sent us another example of an add that implies laxatives lead to happier moms and better family lives:

Part of the text:

“My mum loves me now. I can tell because her hands are gentler…her voice is sweeter…and her kisses are softer. I know know what I did. But all of a sudden she just started loving me!”

Linda, dear, you didn’t do anything. It was Mum’s chemist. He gave her Bile Beans…

Aaron B. sent in this 1947 video clip (found here), titled “Are You Popular?”:

Notice the caution to women: if you go “parking with all the boys,” you might think you’re popular, but you’ll ultimately find yourself ostracized and friendless. To be really popular, you need to be well-dressed, have the respect of girls at school, and carefully guard your reputation.

Thanks, Aaron!

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.

In a comment a while back, Elena pointed out that Diego Velázquez’s painting “Infante Felipe Próspero” (from 1659) provides a good example of how pink was acceptable for males to wear…as were, in some cases, dresses, which the young prince is wearing:

Elena says,

…until the late 1700s little boys would wear dresses or petticoats for as long as they could until they could dress as miniature adults…This was mainly for ease of bodily functions.

Of course, today most parents would be appalled at the idea of dressing toddler boys in dresses–dresses with frills and ribbons, at that.

The painting “Pope Innocent X,” also by Velázquez (1650) shows the Pope in light pink clothing:

Both images found at the National Gallery’s Velázquez page.

You might also check out Kent State University Museum’s Centuries of Childhood exhibit for examples of how children’s clothing has changed over time.

Thanks for the tip, Elena!

Speaking as a 30-year-old who still cherishes a threadbare, 29-year-old specimen, I can personally testify that teddy bears are objects highly charged with affect in modern U.S. bourgeois white society. Along with blankets, stuffed animals are frequently given to young children to play with. Many times, children grow attached to their animals and blankets, naming them, talking to them, sleeping with them and taking them everywhere.

In 1951, Donald Winnicott called such stuffed animals and security blankets “transitional objects.” I’m probably grossly simplifying this, but he posited that transitional objects occupy an important position in children’s emotional lives as mechanisms by which they soothe themselves as they differentiate their identities from those of their parents. Parenting advice emphasizes that transitional objects are part of a “normal and healthy phase of development” and even a “good thing” that parents may want to voluntarily introduce to anxious children.

In short, modern middle-class bourgeois white society associates teddy bears with a deep emotional connection between people. Teddy bears symbolize comfort and a nurturing parent-child bond. To many, they are images of love.

Over on its Web site for investors, Vermont Teddy Bear literally capitalizes on the “bears=love” connotations by couching its business in terms that suggest relationships and closeness. In this screenshot from the investor relations home page, for example, you can see that the over-the-phone sales staff are called “Bear Counselors,” suggesting that they give advice and mentoring about relationships.

On the page entitled “Our Bear-Gram Story,” Vermont Teddy Bear positions its product as equivalent to the emotional work of creating and sustaining authentic relationships. The “story” says:

Once upon a time, people connected with people simply and directly. They took the time to nurture personal relationships. Then it all got crazy, fast-paced, and hectic and people didn’t have time anymore to pay enough attention to other people.

Of course, the thought that it was so good back in Ye Olde Non-Hectick Tymes is problematic, but so is the thought that teddy bears will suffice instead of “pay[ing] attention to other people.” Why expend all that effort relating to someone when you can just toss him or her a teddy bear instead?

On the company’s site for customers, the same association between the toys and love appears, as evidenced by this banner proclaiming the teddy bears as “heartfelt,” an adjective usually used to describe significant declarations of sentiment:

For occasions that require difficult, emotionally draining “relationship work,” there’s even a whole category of “I’m Sorry/Apology” bears available to send.

The I’m Sorry Bear comes with the following descriptive copy:

Whether you’ve broken their heart or their favorite coffee mug this Bear has got it covered. Holding a light blue pillow embroidered with the an “I’m Sorry” message and wearing a matching light blue bowtie, this Bear is a sure way to earn their forgiveness.

Ah, what price forgiveness?

Well, it’s $73.95. [Shipping and handling excluded. Insurance and rush orders extra. Please ask for international rates. Customs taxes may apply outside U.S. Order early to insure delivery by Christmas!]

I suppose that Vermont Teddy Bear’s deployment of a stuffed animal to do your emotional work for you is in the same category as ad campaigns for diamonds and credit cards that promise viewers intimacy through purchase of the products. However, Vermont Teddy Bear’s use of the “objects will fulfill you” trope is slipperier in part because a substantial number of potential consumers have experience with teddy bears as transitional objects that did [or still do] make them feel happy and calm.

In an amusing postscript, I grew up in Vermont, where we were kind of expected to support Vermont Teddy Bear Company. But when someone gave my younger brother a Vermont Teddy Bear as a gift, he never touched it. Finding the bear stiff and kind of lumpy, he preferred to drag around smaller and more squishable stuffed animals. No one else in the family was impressed with its cuddlability, not even me, and I was the one who collected stuffed animals to line the edges of my bed every night. The bear is now sitting on my mom’s desk as a display item, having not created an emotional connection at all.