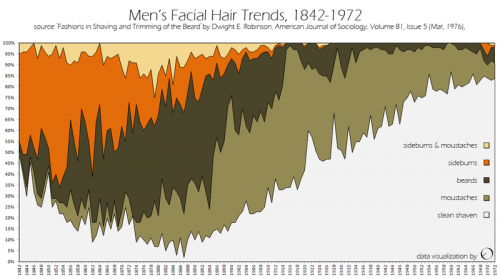

Recently we ran a graph showing the evolution of facial hair trends starting in 1842. It showed that about 90% of men wore facial hair in the late 1800s, but it was a trend that would slowly die. By 1972, when the research was published, almost as many were clean shaven.

So, why did facial hair fall out of fashion?

Sociologist Rebekah Herrick gives us a hypothesis. With Jeanette Mendez and Ben Pryor, she investigated the stereotypes associated with men’s facial hair and the consequences for U.S. politicians. Facial hair is rare among modern politicians. “Currently,” they noted, “fewer than five percent of the members of the U.S. Congress have beards or mustaches” and no president has sported facial hair since William Howard Taft left office in 1913, before women had the right to vote.

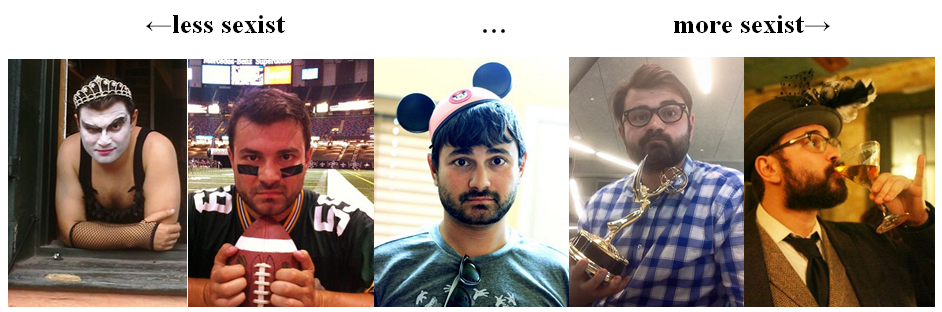

Using an experimental method, Herrick and her colleagues showed people photographs of similarly appearing politicians with and without facial hair, asking them how they felt about the men and their likely positions. They found that potential voters perceived men with facial hair to be more masculine and this was a double edged sword. Higher ratings of masculinity were correlated with perceptions of competence, but also concerns that the politicians were less friendly to women and their concerns.

In other words, the more facial hair, the more people worry that a politician might be sexist:

In reality, facial hair has no relationship to a male politician’s voting record. They checked. The research suggests, though, that men in politics — maybe even all men — would be smart to pay attention to the stereotypes if they want to influence how others see them.

Thanks to my friend, Dmitriy T.C., for use of his face!

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.