Cross-posted at Jezebel.

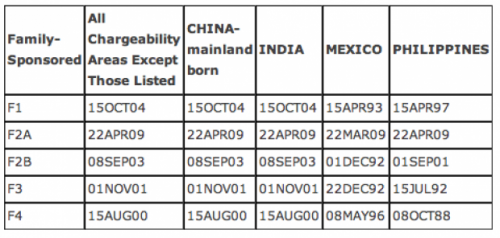

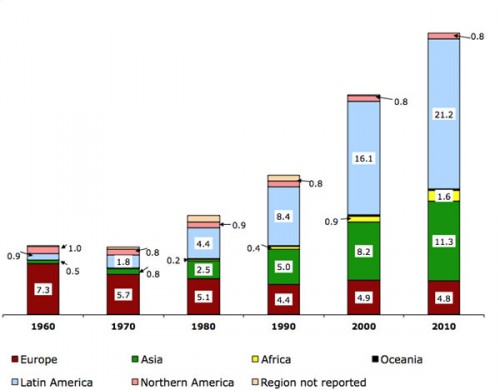

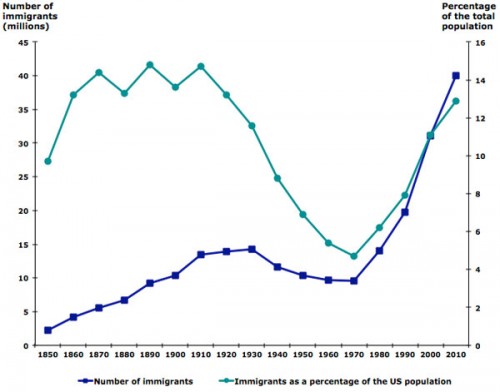

Yesterday I posted about U.S. immigration trends, updated through 2010. Following up on that, Dolores R. found another immigration-related post by KPCC…this time, a look at the wait time to get a family-sponsored immigration visa. With the removal of strict, racialized quotas in 1965, the U.S. turned to a policy based on a set of priorities for deciding who would be granted a visa; among the various categories was a preference for those who had sponsoring relatives already living in the U.S., with different visas and priorities based on family relationship:

- F1 = unmarried adult children of U.S. citizens

- F2A = spouses and children (under age 21) of permanent residents

- F2B = unmarried adult children of permanent residents

- F3 = married adult children of U.S. citizens

- F4 = siblings of adult U.S. citizens

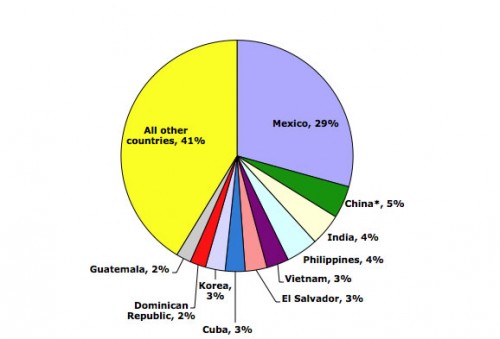

According to the U.S. State Department, the annual minimum family-reunification visa target is 226,000 (note that this excludes spouses, parents, and minor children of U.S. citizens, who are highest priority for immigration and are exempt from immigration caps). The Immigration and Naturalization Act requires that family-sponsorsed (as well as employer-sponsored) visas be granted in the order that eligible potential immigrants applied. Unsurprisingly, many years there are more eligible applicants than there are available visas, leading to a backlog of individuals who qualify to immigrate but are waiting for a visa to become available. In particular, China, Mexico, India, and the Philippines are “oversubscribed,” meaning there is a significant backlog.

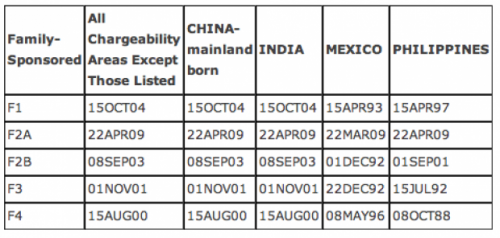

How long? The table below shows the cut-0ff date for visa applicants in each category as of January 2012. That is, the dates given here are the date by which a person had to apply to finally have a visa available this month; the 2nd column shows for all areas excluding the four countries singled out because of their particularly long wait times:

The least oversubscribed visa category is the F2A, where those now receiving visas will have waited a bit under 3 years. But look at some of the other dates listed. For F1, F2B, and F3 visas from Mexico, the people now at the head of the line have been waiting nearly two decades, having applied in 1992 or early 1993. F4 applicants from the Philippines have been waiting almost a quarter century, since 1988.

The least oversubscribed visa category is the F2A, where those now receiving visas will have waited a bit under 3 years. But look at some of the other dates listed. For F1, F2B, and F3 visas from Mexico, the people now at the head of the line have been waiting nearly two decades, having applied in 1992 or early 1993. F4 applicants from the Philippines have been waiting almost a quarter century, since 1988.

This is part of the reason why undocumented immigration continues, and arguments about fairness and waiting their turn in line may not be particularly compelling to individuals who want to reunite with family members in the U.S. Waiting a year, or two, or five, may seem reasonable. If you learn there’s a 20-year wait, the cost/benefit analysis of whether to wait for the visa to come through or to find other means may shift significantly, regardless of how otherwise law-abiding a person might be.