Cross-posted at Racialicious and Family Inequality.

Trying to summarize a few historical trends for the last half century, I thought of framing them in terms of diversity.

Diversity is often an unsatisfying concept, used to describe hierarchical inequality as mere difference. But inequality is a form of diversity — a kind of difference. And further, not all social diversity is inequality. When people belong to categories and the categories are not ranked hierarchically (or you’re not interested in the ranking for whatever reason), the concept of diversity is useful.

There are various ways of constructing a diversity index, but I use the one sometimes called the Blau index, which is easy to calculate and has a nice interpretation: the probability that two randomly selected individuals are from different groups.

Example: Religion

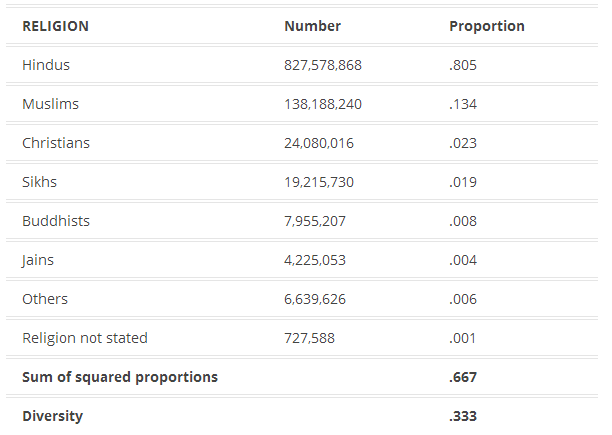

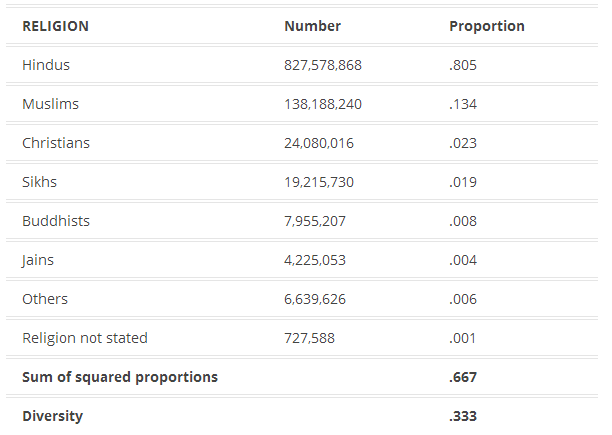

Take religion. According to the 2001 census of India, this was the religious breakdown of the population:

Diversity is calculated by summing the squares of the proportions in each category, and subtracting the sum from 1. So in India in 2001, if you picked two people at random, you had a 1/3 chance of getting people with different religions (as measured by the census).

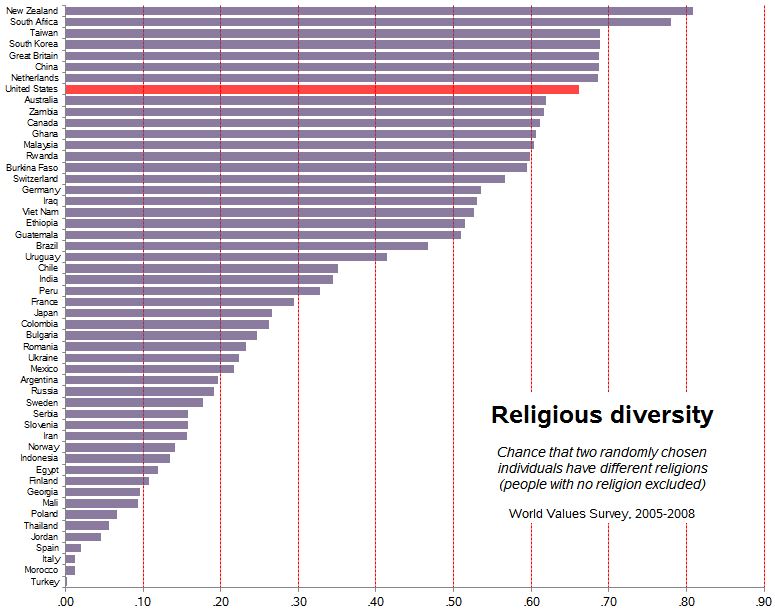

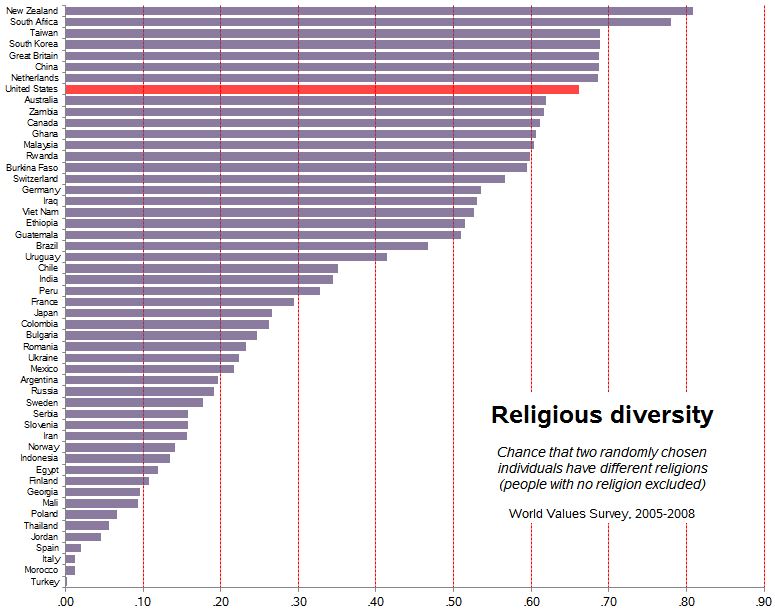

Is .33 a lot of religious diversity? Not really, it turns out. I was surprised to read on the cover of this book by a Harvard professor that the United States is “the world’s most religiously diverse nation.” When I flipped through the book, though, I was disappointed to see it doesn’t actually talk much about other countries, and does not seem to offer the systematic comparison necessary to make such a claim.

With our diversity index, it’s not hard to compare religious diversity across 52 countries using data from World Values Survey, with this result:

The U.S. is quite diverse — .66 — but a number of countries rank higher.

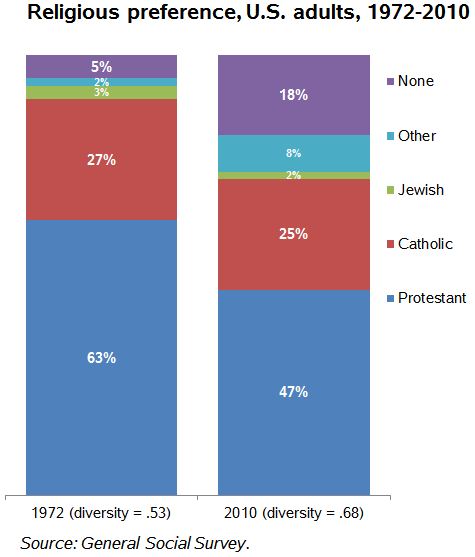

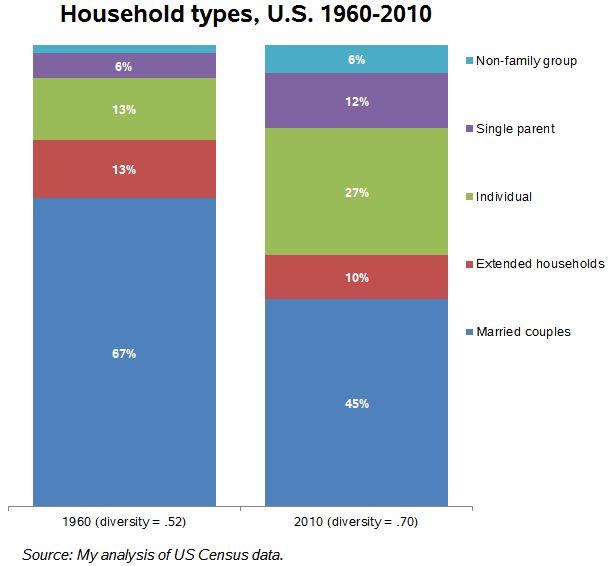

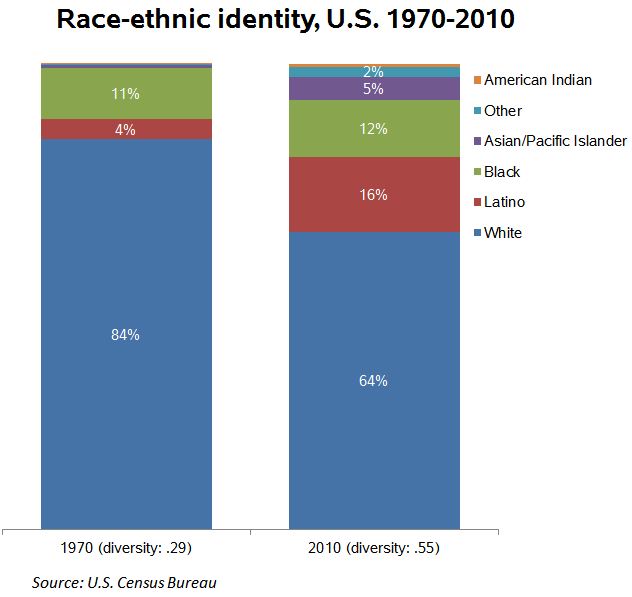

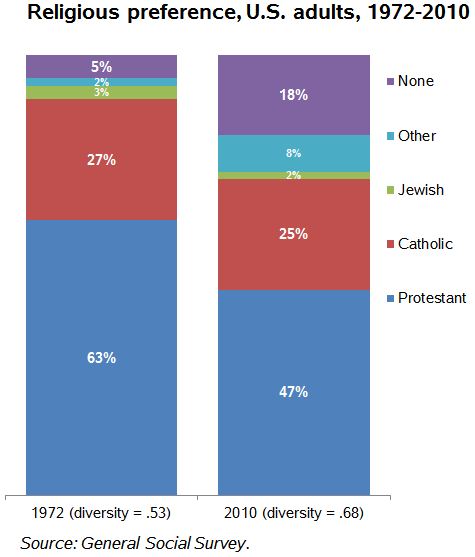

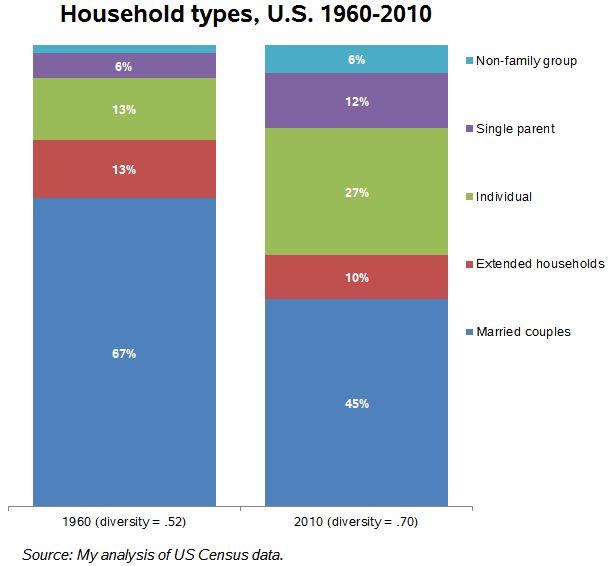

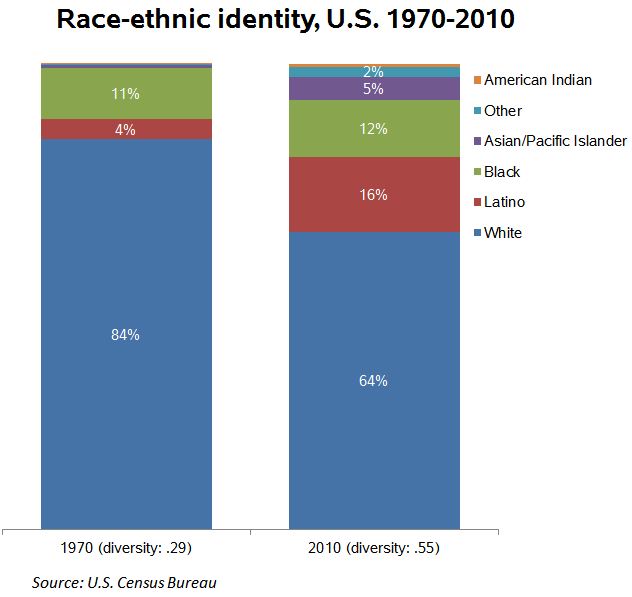

Increasing U.S. Diversity

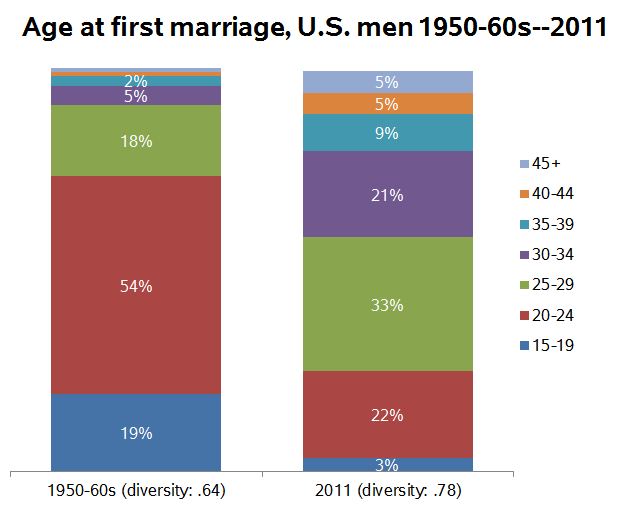

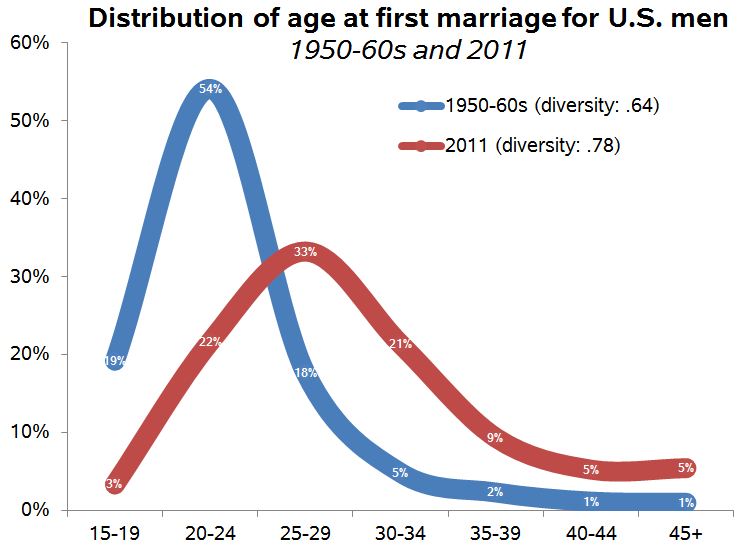

Anyway, back to describing the last half century in the U.S. On four important measures I’ve got easy-to-identify increasing diversity:

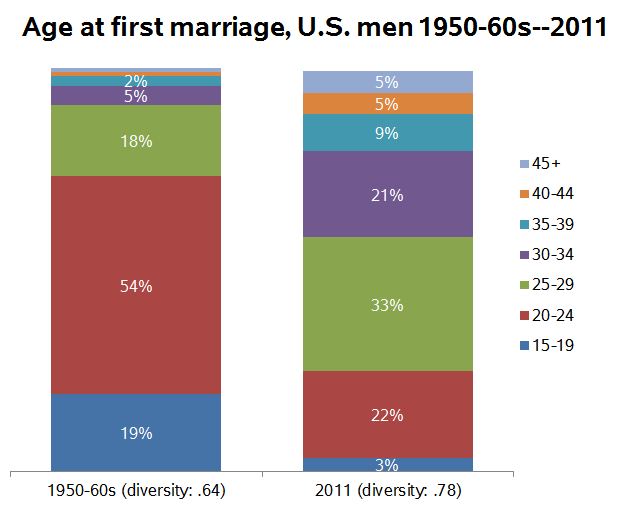

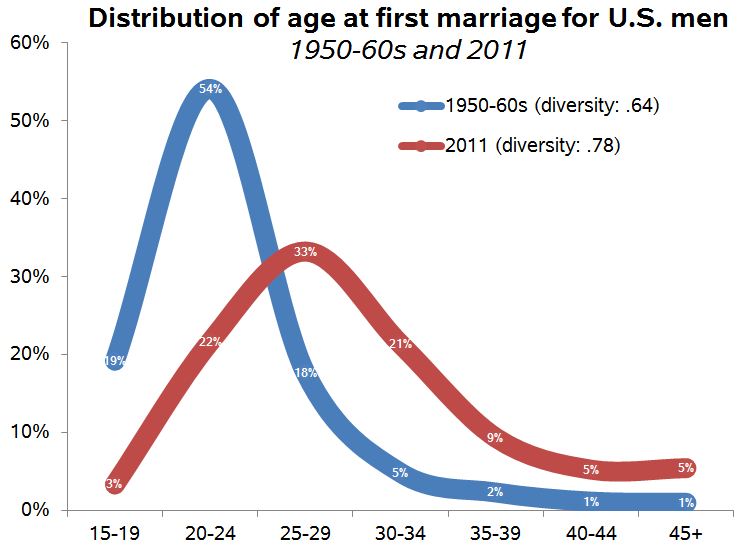

The last one is a little tricky. It’s common to report that the median age at marriage has increased since the 1950s (having fallen before the 1950s). But I realized it’s not just the average increasing, but the dispersion: More people marrying at different ages. So the experience of marriage is not just shifting rightward on the age distribution, but spreading out. Here’s another view of the same data:

I calculated these using the Panel Study of Income Dynamics from 1968 (for those married in the years 1950-1968) and comparing it with the 2011 American Community Survey for those married in the previous year. There might be a better way, of course.

I have complained before that using the 1950s or thereabouts as a benchmark is misleading because it was an unusual period, marked by high conformity, especially with regard to family matters. But it is still the case that since then diversity on a number of important measures has increased. Over the period of several generations, in important ways the people we randomly encounter are more likely to be different from ourselves (and each other).

Philip N. Cohen is a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland, College Park, and writes the blog Family Inequality. You can follow him on Twitter or Facebook.

In this charming minute-and-a-half, Walter Cronkite demos the home office of 2001, as envisioned in 1967. Amazingly, reality seems to have far outpaced their imagination!

In this charming minute-and-a-half, Walter Cronkite demos the home office of 2001, as envisioned in 1967. Amazingly, reality seems to have far outpaced their imagination!