Cross-posted at Family Inequality.

I haven’t yet seen any definitive evidence that the recession has had an effect on divorce rates. But if I’m going to pick on other people for this, I should offer a few ideas.

In a previous post I cited a lot of reasons to expect divorce would increase as a result of family stress and instability. Others claim these hard times are bringing couples together in the face of adversity. And either – or both – of these influences is woven into the long term trends in divorce. Here are three graphs looking at the question.

Long-term trends

The overall divorce trend doesn’t seem to be moved much one way or the other by recessions (shown in blue), at least for the last 60 years:

That national data is only available through 2009, so a little early to see a major effect. Still, no disruption of the trend at the national level, just a continuous decline in the divorce rate. (Here’s a great recent Census report on divorce trends.)

State patterns

The official divorce rates are available from 38 states, but they’re only considered reliable through 2008 so far. By putting together two years of changes — 2006-2007 and 2007-2008 — this figure has 76 dots (two for each state), showing whether changes in divorce are related to changes in unemployment rates. This gives a rough idea of the relationship between how hard states were hit by the recession and any changes in divorce:

I made the dots larger according to the population sizes, and weighted the red trend line so that the larger states have more effect (this positive relationship is statistically significant at the 99% confidence level). This is just a start, but it leans in the direction of unemployment increasing divorces. At least it doesn’t look like the recession is driving divorce down.

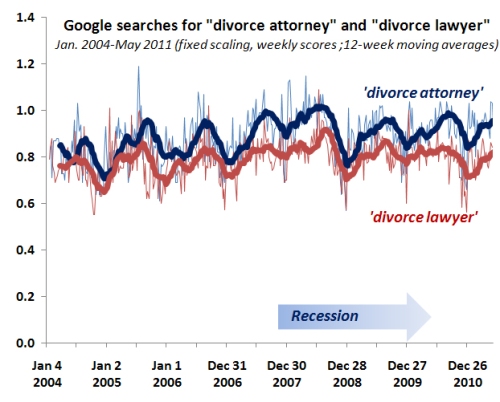

Finally, what about divorce on the American brain? For a glimpse inside, we turn to Google trends. If it works for the flu, it might work for divorce, too. Here are the trends for “divorce attorney” and “divorce lawyer”:

The trend for both searches looks basically flat except for seasonal variation, and some turbulence in 2008. But nothing to suggest a major trend one way or the other. (You can play with these yourself, starting with mine, here.)

My conclusion so far: no national evidence of a recession effect on divorce yet, but some suggestive hints worth keeping an eye on — leaning in the direction of recession causing more divorces — in opposition to a long-term downward trend. Maybe if and when the housing market loosens up more unhappy spouses will take the plunge and move out. The divorce rate may continue to fall, as it has been since the early 1980s, but that doesn’t mean this recession has a “silver lining” for families.