Apparently universities are issuing guidelines to help professors consider adding “trigger warnings” to syllabi for “racism, classism, sexism, heterosexism, cissexism, ableism, and other issues of privilege and oppression,” and to remove triggering material when it doesn’t “directly contribute to learning goals.” One example given is Chinua Achebe’s “Things Fall Apart” for its colonialism trigger. This from New Republic this week.

I have no desire to enter the fray of online discussions on trigger warnings and sensitivity. I have used trigger warnings. Most recently, I made a personal decision to not retweet Dylan Farrow’s piece in the New York Times detailing Woody Allen’s sexual abuse. I was uncomfortable shoving a very powerful description at people without some kind of warning. I couldn’t read past the first three sentences. I couldn’t imagine how it read for others. So, I referenced the article with a trigger warning and kept it moving.

But, I’m not sure that’s at all the kind of deliberation universities are doing with their trigger warning policies. Call me cynical, but the “student-customer” movement is the soft power arm of the neo-liberal corporatization of higher education. The message is that no one should ever be uncomfortable because students do not pay to feel things like confusion or anger. That sounds very rational until we consider how the student-customer model doesn’t silence power so much as it stifles any discourse about how power acts on people.

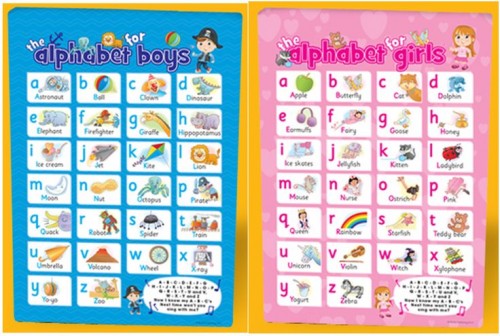

I’ve talked before about how the student-customer model becomes a tool to rationalize away the critical canon of race, sex, gender, sexuality, colonialism, and capitalism.

The trigger warned syllabus feels like it is in this tradition. And I will tell you why.

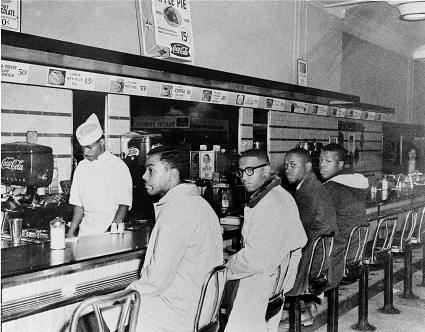

In the last three weeks alone: a college student has had structural violence of normative harassment foisted on her for daring to have sex (for money), black college students at Harvard have taken to social media to catalog the casual racism of their colleagues, and black male students at UCLA made a video documenting their erasure.

It would seem that the most significant “issue” for a trigger warning is actual racism, sexism, ableism, and systems of oppression. Cause I’ve got to tell you, I’ve had my crystal stair dead end at the floor of racism and sexism and I’ve read “Things Fall Apart.” The trigger warning scale of each in no way compares.

Yet, no one is arguing for trigger warnings in the routine spaces where symbolic and structural violence are acted on students at the margins. No one, to my knowledge, is affixing trigger warnings to department meetings that WASP-y normative expectations may require you to code switch yourself into oblivion to participate as a full member of the group. Instead, trigger warnings are being encouraged for sites of resistance, not mechanisms of oppression.

At for-profit colleges, strict curriculum control and enrollment contracts effectively restrict all critical literature and pedagogy. We elites balk at such barbarism. What’s a trigger warning but the prestige university version? A normative exclusion as opposed to a regulatory one?

Trigger warnings make sense on platforms where troubling information can be foisted upon you without prior knowledge, as in the case of retweets. Those platforms are in the business of messaging and amplification.

That is an odd business for higher education to be in… unless the business of higher education is now officially business.

In which case, we may as well give up on the tenuous appeal we have to public good and citizenry-building because we don’t have a kickstand to lean on.

If universities are not in the business of being uncomfortable places for silent acts of power and privilege then the trigger warning we need is: higher education is dead but credential production lives on; enter at your own risk.

Tressie McMillan Cottom is a PhD candidate in the Sociology Department at Emory University in Atlanta, GA. Her doctoral research is a comparative study of the expansion of for-profit colleges. You can follow her on twitter and at her blog, where this post originally appeared.

Thanks Jen T., Lisa S., @nayohmei, and @doubleemmartin!

Thanks Jen T., Lisa S., @nayohmei, and @doubleemmartin!