Flashback Friday.

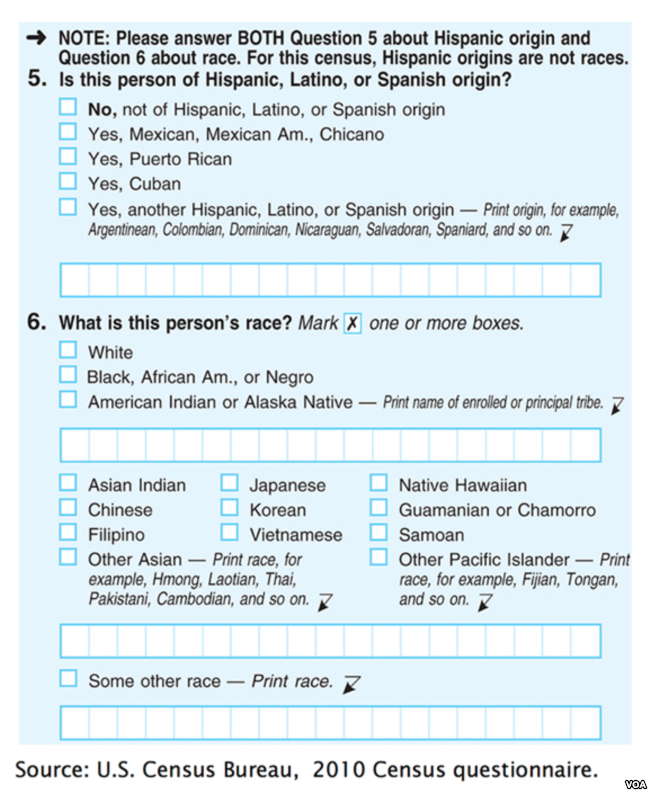

Social and biological scientists agree that race and ethnicity are social constructions, not biological categories. The US government, nonetheless, has an official position on what categories are “real.” You can find them on the Census:

These categories, however real they may seem, are actually the product of a long process. Over time, the official US racial categories have changed in response to politics, economics, conflict, and more. Here’s some highlights.

In the year of the first Census, 1790, the race question looked very different than it does today:

Free white males

Free white females

All other free persons (included Native Americans who paid taxes and free blacks)

And slaves

By 1870 slavery is illegal and the government was newly concerned with keeping track of two new kinds of people: “mulattos” (or people with both black and white ancestors) and Indians:

White

Black

Mulatto

Indian (Native Americans)

Between 1850 and 1870 6.5 million Europeans had immigrated and 60,000 Chinese. Chinese and Japanese were added for the 1880 Census.

By 1890, the U.S. government with obsessed with race-mixing. The race question looked like this:

White

Black (3/4th or more “black blood”)

Mulatto (3/8th to 5/8th “black blood”)

Quadroons (1/4th “black blood”)

Octoroons (1/8th or any trace of “black blood”)

Indian

Chinese

Japanese

This year was the only year to include such fine-tuned mixed-race categories, however, because it turned out it wasn’t easy to figure out how to categorize people.

In the next 50 years, the government added and deleted racial categories. There were 10 in 1930 (including “Mexican” and “Hindu”) and 11 in 1940 (introducing “Hawaiian” and “Part Hawaiian”). In 1970, they added the “origin of descent” question that we still see today. So people are first asked whether they are “Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish” and then asked to choose a race.

You might immediately think, “But what do these words even mean?” And you’d be right to ask. “Spanish” refers to Spain; “Latino” refers to Latin America; and “Hispanic” is a totally made up word that was originally designed to mean “people who speak Spanish.”

Part of the reason we have the “Hispanic” ethnicity question is because Mexican Americans fought for it. They thought it would be advantageous to be categorized as “white” and, so, they fought for an ethnicity category instead of a racial one.

Funny story: The US once included “South American” as a category in the “origin of descent” question. That year, over a million residents southern U.S. states, like Alabama and Mississippi checked that box.

2000 was the first year that respondents were allowed to choose more than one race. They considered a couple other changes for that year, but decided against them. Native Hawaiians had been agitating to be considered Native Americans in order to get access to the rights and resources that the US government has promised Native Americans on the mainland. The government considered it for 2000, but decided “no.” And whether or not Arab American should be considered a unique race or an ethnicity was also discussed for that year. They decided to continue to instruct such individuals to choose “white.”

The changing categories in the Census show us that racial and ethnic categories are political categories. They are chosen by government officials who are responding not to biological realities, but to immigration, war, prejudice, and social movements.

This post originally appeared in 2010.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.