Cross-posted at Neuroskeptic.

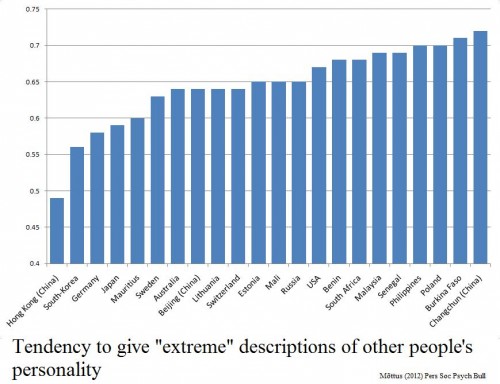

“Personality differences” between people from different countries may just be a reflection of cultural differences in the use of “extreme” language to describe people.

That’s according to a very important paper just out from an international team led by Estonia’s René Mõttus.

There’s a write up of the study here. In a nutshell, they took 3,000 people from 22 places and asked them to rate the personality of 30 fictional people based on brief descriptions (which were the same, but translated into the local language). Ratings were on a 1 to 5 scale.

It turned out that some populations handed out more of the extreme 1 or 5 responses. Hong Kong, South Korea and Germany tended to give middle of the road 2, 3 and 4 ratings, while Poland, Burkina Faso and people from Changchun in China were much more fond of 1s and 5s.

The characters they were rating were the same in all cases, remember.

Crucially, when the participants rated themselves on the same personality traits, they tended to follow the same pattern. Koreans rated themselves to have more moderate personality traits, compared to Burkinabés who described themselves in stronger tones.

Whether this is a cultural difference or a linguistic one is perhaps debatable; it might be a sign that it is not easy to translate English-language personality words into certain languages without changing how ‘strong’ they sound. However, either way, it’s a serious problem for psychologists interested in cross-cultural studies.

I’ve long suspected that something like this might lie behind the very large differences in reported rates of mental illness across countries. Studies have found that about 3 times as many people in the USA report symptoms of mental illness compared to people in Spain, yet the suicide rate is almost the same, which is odd because mental illness is strongly associated with suicide.

One explanation would be that some cultures are more likely to report ‘higher than normal’ levels of distress, anxiety — a bit like how some make more extreme judgements of personality.

So it would be very interesting to check this by comparing the results of this paper to the international mental illness studies. Unfortunately, the countries sampled don’t overlap enough to do this yet (as far as I can see).

Source: Mõttus R, et al (2012). The Effect of Response Style on Self-Reported Conscientiousness Across 20 Countries. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin PMID: 22745332

————————

Neuroskeptic blogs anonymously here. You can also follow him on Twitter.