Experimenting here a bit, so GWP readers and writers, bear with me! For a piece I’m writing, I’m collecting all the metaphors scholars and advocates use to talk about the “straightjacket” that gender identity can be. Like, well, “straightjacket.” And “box.” What else are people using these days? Please share, in comments, on my FB page, or tweet me @girlmeetsvoice – GO!

GO!

If women can kiss women and still be straight, what about men?

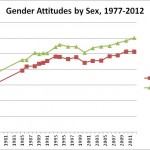

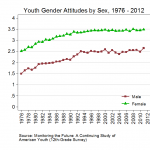

Some scholars have argued that female sexual desires tend to be fluid and receptive, while men’s desires – regardless of whether men are gay or straight – tend to be inflexible and unchanging. Support for this notion permeates popular culture. There are countless examples of straight-identified female actresses and pop stars kissing or caressing other women – from Madonna and Britney to Iggy and J-Lo – with little concern about being perceived as lesbians. When the Christian pop star Katy Perry sang in 2008 that she kissed a girl and liked it, nobody seriously doubted her heterosexuality.

The story is different for men. The sexuality of straight men has long been understood by evolutionary biologists, and, subsequently, the general public, as subject to a visceral, nearly unstoppable impulse to reproduce with female partners. Consequently, when straight men do engage in same sex contact, these encounters are viewed as incompatible with the bio-evolutionary coding. It’s believed to signal an innate homosexual (or at least bisexual) orientation, and even just one known same-sex act can cast considerable doubt upon a man’s claim to heterosexuality. For instance, in 2007, Republican Senators Larry Craig and Bob Allen were both separately arrested on charges related to sex with men in public bathrooms. While both men remained married to their wives and tirelessly avowed their heterosexuality, the press skewered them as closeted hypocrites.

Despite the common belief in the rigidity of male heterosexuality, historians and sociologists have created a substantial body of well-documented evidence showing straight men – not “closeted” gay men – engaging in sexual contact with other men. In many parts of the United States prior to the 1950s, the gay/straight binary distinguished between effeminate men (or “fairies”) and masculine men (“normal” men) – not whether or not a man engaged in homosexual sex. Historian George Chauncey’s study of gay life in New York City from 1890-1940 revealed that through much of the first half of the 20th century, normal (i.e., “straight”) working class men mixed with fairies in the saloons and tenements that were central to the lives of working men.

With sex-segregation the general rule for single men and women in the early 1900s, the private back rooms of saloons were often sites of sexual activity between normal men and fairies, with the latter perceived as a kind of intermediate sex – a reasonable alternative to female prostitutes. Public parks and restrooms were also common sites for sexual interaction between straight men and fairies. In such encounters, the fairy acted as the sole embodiment of queerness, the figures with whom normal (straight) men could have sex – just as they might with female sex workers. Fairies affirmed, rather than threatened, the heteromasculinity of straight men by embodying its opposite.

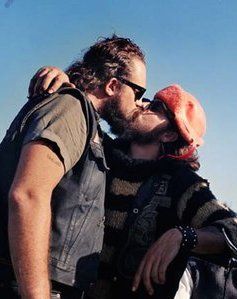

The notion that homosexual activity was not “gay” when undertaken by “real” (i.e. straight) men continued into the 1950s and 60s. During this period, the homosexual contact of straight men began to be undergo a transformation from relatively mundane behavior to the bold behavior of male rebels. The American biker gang The Hells Angels, which formed in 1948, serves as a rich example. There are few figures more “macho” than a heavily tattooed, leather-clad biker, whose heterosexuality was as much on display as his masculinity. Brawling over women, exhibiting women on the back of bikes, and brandishing tattoos and patches of women were all central to the subculture of the gang.

Yet as the journalist Hunter S. Thompson documented in his 1966 book Hell’s Angels: A Strange and Terrible Saga, gang members also had sexual encounters with one another. One of their favorite “stunts” was to deeply French kiss one another – with tongues extended out of their mouths in a type of tongue-licking kiss often reserved for girl-on-girl porn. Members of the Hells Angels explained that the kissing was a defiant stunt that produced among onlookers the desired degree of shock. To them, it was also an expression of “brotherhood.”

Today, sexual encounters between straight-identified men take new but similarly “manly” forms. For instance, when men undergo hazing in college fraternities and in the military, there’s often a degree of sexual contact. It’s often dismissed as a joke, game, or ritual that has no bearing on the heterosexual constitution of the participants. As I document in my forthcoming book, fraternity hazing has included practices such as the “elephant walk,” in which pledges are required to strip naked and stand in a circle, with one thumb in their mouth and the other in the anus of the pledge in front of them.

Similarly, according to anthropological accounts of the Navy’s longstanding “Crossing the Line” initiation ceremony, new sailors crossing the equator for the first time have garbage and rotten food shoved into their anuses by older sailors. They’re also required to retrieve objects from one another’s anuses.

One relatively recent example of the pervasiveness of these kinds of encounters between straight men was revealed in a report by the US-based watchdog organization Project on Government Oversight. In 2009, the group released photos of American security guards at the U.S. Embassy in Kabul engaging in “deviant” after-hours pool parties. The photos show the men drunkenly urinating on each other, licking each other’s nipples, and taking vodka shots and eating potato chips out of each other’s butts.

Individuals often react to these examples in one of two ways. Either they jump to the conclusion that any straight-identified man who engages in sexual contact with another man must actually be gay or bisexual, or they dismiss the behavior as not actually sexual. Rather, they interpret it as an expression of dominance, a desire to humiliate, or some other ostensibly “non sexual” male impulse.

But these responses merely reveal our culture’s preconceived notions about men’s sexuality. Look at it from the other side of the coin: if straight young women, such as sorority pledges, were touching each other’s vaginas during an initiation ritual or taking shots from each other’s butts, commentators would almost certainly imagine these acts as sexual in some way (and not exclusively about women’s need to dominate, for instance). Straight women are also given considerable leeway to have occasional sexual contact with women without the presumption that they are actually lesbians. In other words, same-sex contact among straight men and women is interpreted through the lens of some well-worn gender stereotypes. But these stereotypes don’t hold up when we examine the range of straight men’s sexual encounters with other men.

It’s clear that straight men and women come into intimate contact with one another in a range of different ways. But this is less about hard-wired gender differences and more about broader cultural norms dictating how men and women are allowed to behave with people of the same sex. Instead of clinging to the notion that men’s sexuality is fundamentally inflexible, we should view male heterosexuality for what it is – a fluid set of desires that are constrained less by biology than by prevailing gender norms.

____________________

Jane Ward is an Associate Professor of Gender and Sexuality Studies at The University of California, Riverside, where she teaches courses in feminist, queer, and heterosexuality studies. She has published on a broad range of topics including: feminist pornography; queer parenting; gay pride festivals; gay marriage campaigns; transgender relationships; the social construction of heterosexuality; the failure of diversity programs; and the evolution of HIV/AIDS organizations. This post is based on research for a forthcoming book with NYU Press–Not Gay: Sex between Straight White Men.

Jane Ward is an Associate Professor of Gender and Sexuality Studies at The University of California, Riverside, where she teaches courses in feminist, queer, and heterosexuality studies. She has published on a broad range of topics including: feminist pornography; queer parenting; gay pride festivals; gay marriage campaigns; transgender relationships; the social construction of heterosexuality; the failure of diversity programs; and the evolution of HIV/AIDS organizations. This post is based on research for a forthcoming book with NYU Press–Not Gay: Sex between Straight White Men.