In February 2013, I gave a TEDx talk at TEDxWindyCity about the gendering of childhood in the earliest years of life. TEDx events, for those who may not know what the “x” stands for, are independently organized TED-like experiences created in the spirit of TED’s mission, “ideas worth spreading,” only at the local level. So, in an auditorium along the frozen shores of Lake Michigan, I stood on a stage before a sold-out crowd of 650 smart Chicagoans, said things like “gender binary”, and wore a pair of mismatched pink and blue tights.

In February 2013, I gave a TEDx talk at TEDxWindyCity about the gendering of childhood in the earliest years of life. TEDx events, for those who may not know what the “x” stands for, are independently organized TED-like experiences created in the spirit of TED’s mission, “ideas worth spreading,” only at the local level. So, in an auditorium along the frozen shores of Lake Michigan, I stood on a stage before a sold-out crowd of 650 smart Chicagoans, said things like “gender binary”, and wore a pair of mismatched pink and blue tights.

Preparing for and delivering this talk were some rather peak experiences this year.

I’ve since received many questions about the process: “Did you audition, self-nominate, or get tapped?” “How long did it take you to prepare?” “Did you receive training?” “How’d you do it without notes?” “Where’d you get those tights?” (A: I made them.)

There’s a real hunger, I’ve learned, to know more about what goes on behind the scenes. And I’ll tell you. But first, please know that like many public thought leadership forums, women could afford to lean in here a bit more. When speaking to my authors group back in New York City, Kelly Stoetzel, Content Director and curator for the mothership TED said that women turn down invitations to speak at TED with far greater frequency than do men. If the phone rings, lady readers, and it’s TED calling, promise me one thing before continuing to read this post. Promise me you’ll say yes.

But you don’t have to wait for the phone to ring to speak at a TEDx event. Unlike TED, which invites its speakers, TEDx events are fully planned and coordinated on a community-by-community basis, and the organizers often outline their submission process clearly on the event’s site.

TEDx talks can lead to TED invitations. They can lead to media appearances, speaking engagements, and books. Regardless of doors opened and views accrued, preparing for and giving a TEDx talk is a valuable experience in and of itself.

I say giving this talk changed my life because it did. It got me out of a writing rut and pushed me into multimedia. It ushered me into a new city and gave me a local calling card (I relocated from New York last July). And it taught me that I could experience more joy while giving a talk than I ever knew was possible. That’s right, people. Joy.

Much of the joyfulness I attribute to the organizers. (Shannon Downey of Pivotal Productions, you are a one-woman bundle of brilliance.) A team of 20 volunteers (aka the Dream Team) did a seamless job producing the event, and co-sponsors included the Museum of Science and Industry and the Ravinia Festival, which catered a mid-day indoors picnic on astroturf. Ten speakers shared the stage with dancers, poets, and a comedic duo. The audience, too, was key. Everyone there was interesting. The mood was one of mutual inspiration and support. TEDx events are a reflection of their organization, and this one was tops. Not every event will explode with this level of creativity and be this well organized, but the trick is to make the most of it, whatever the production level, because one TEDx can also lead to the next.

Here’s how mine went down:

July 2012: A friend sends me a call for speakers for TEDxWindyCity. The theme is “contrast.” I have girl/boy twins. I write about gender. I decide to propose a talk that brings to life key research about the gendering of childhood in the earliest years of life. With help from a filmmaker friend (who also happens to be a girl/boy twin mama), I prepare the requested 2-minute video submission using a 500-word script, an ultrasound video, and some stills. I write a short proposal explaining how, adhering to the TEDxWindyCity Commandments, I intend to inspire listeners to think beyond convention; innovate by unearthing the studies that turn previous findings upside down; revolutionize the way listeners think about not only the gendering of the tiny, but the gendering of the adults who shape them; move listeners by speaking very personally about my experience as a new mother of boy/girl twins who, after years of studying and writing about gender in theory, suddenly found herself in the belly of the beast and questioning her core beliefs; influence by launching a Pinterest board in which I ask followers to post a photo of a young child breaking or upholding a gender norm; entertain with a brief slideshow; and, above all, inform. I explain that my inquiry is part of a larger project, I explain who I am, I send a few links related to the project and to previous talks and videos, and I attach a few testimonials attesting to my speaking skills.

September 2012: I’m accepted. (I think: Huzzah! Then: Oh lord, what have done?)

October 2012: I stall. Or, put another way, I try to figure out a talk that will also help me think toward the book I’m (slowly) working on. I end up going in circles, trying to do too much at once.

November 2012: I receive an email from the organizers:

As you know your TEDx talk needs to tell a story or argue for an idea. I need you to please submit to me the title of your talk + in 5 sentences or less the thesis statement/main point of your talk. You can find a million examples on TED.com

I’m reminded to think short, and think pithily. I come up with the following: “Learn, from kids, to embrace paradox and get out of your gender binary zone.”

December 2012: I’m freed, now, to write the talk. I come up with a simple three-part structure, and working backwards from that tagline, I pull together a narrative that interweaves my personal story with research from various fields. I get feedback from my writers group and other trusted advisors.

January 2013: I send my draft to the organizers. I have a month left to revise. The organizers hook us up with a webinar called “The Foundation of Great Presentations,” with Doug Carter and Brian Burkhart of Square Planet. From them, I learn the importance of knowing what I want my audience to know, feel, and do.

Afterwards, I receive an email from Doug:

Remember, this is an ALL IN proposition—you’ve only got one shot at this. There are no “do-overs” like we had when we were kids. No late night cramming on February 22nd hoping that it will magically sink in. You HAVE to work at it to be the best you can possibly be.

I’m inspired to go all in.

February 2013: I revise and revise, tightening and cutting wherever I can. My graphic designer husband (convenient, I know) helps me refine the slides, which I’ve by now come to realize need to be just as concise as the words. A few weeks before the event, the organizers host a pre-show gathering so the speakers and Dream Team can all meet and greet. I spend the last week memorizing my talk, getting it down to just notes on one page, and eventually to notes on a single note card. I practice, practice, and practice some more. I video myself doing it once. The day before, I do a full run-through on stage. The event takes place. I go second and get to enjoy the rest of the day. Everyone does a great job. In the lingo of TEDx, we killed.

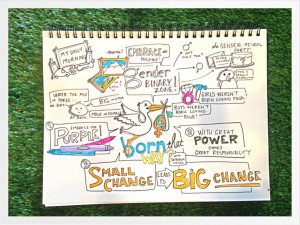

The talk resulted in views and media (like here and here). Ink Factory Studio graphically recorded my talk (see below).

This all, of course, was well and good, but most importantly, for me, preparing for and delivering the talk led to a loosening up. Mixing up the visual and the verbal felt playful and expansive at the same time that it pushed me to be precise. And now, I think I’m hooked.

This all, of course, was well and good, but most importantly, for me, preparing for and delivering the talk led to a loosening up. Mixing up the visual and the verbal felt playful and expansive at the same time that it pushed me to be precise. And now, I think I’m hooked.

To find a TEDx event to apply to near you, click here. http://www.ted.com/tedx

Watch the talk:

Visit the Pinterest Board, Tots in Genderland (and hey, if interested in becoming a pinner, drop me a line!)

Got questions? Please leave them in comments or tweet me (@deborahgirlwpen) and I’ll try my best to answer. Even if they’re just about the tights.

Earlier this month I wrote about

Earlier this month I wrote about  Crossposted at

Crossposted at