By C.J. Pascoe and Tristan Bridges

Last week Bachelor star Juan Pablo Galavis broke my queer little heart (CJ’s heart to be exact. JP has yet to win Tristan over). I—and judging from the interwebs, many others—had fallen for Juan Pablo Galavis. Attractive, sensitive, a dedicated single father, not to mention a talented dancer, Juan Pablo had charmed his way into many of our hearts, gay and straight alike. While he may not have been right for last season’s bachelorette Desiree Hartsock, he certainly seduced the rest of us. That is, until his comments last week.

For those of you who missed it, Galavis had a thing or two to say about whether or not a season featuring a “gay bachelor” would or should ever happen.* As The Huffington Post reported, after claiming to have a gay friend, Galavis said, “No… I respect [gay people] but, honestly, I don’t think it’s a good example for kids… Two parents sleeping in the same bed and the kid going into bed… It is confusing in a sense” and that gay people are “more ‘pervert’ in a sense. And to me the show would be too strong… too hard to watch.” He later attempted to clarify these remarks apologizing to those he “may have offended” stating that he has “nothing but respect for gay people and their families.”

Gay blogs quickly denounced his comments, as did those at ABC. Even Bachelor host Chris Harrison said that he was “disappointed” and that Galavis’ views “obviously don’t reflect my feelings or my thoughts on the subject.” ABC released a statement saying, “Juan Pablo’s comments were careless, thoughtless and insensitive, and in no way reflect the views of the network, the show’s producers or studio.” Apart from some GLBT commentators calling for a stronger statement or some “make-up” activist work, the event seems to have passed relatively quietly.

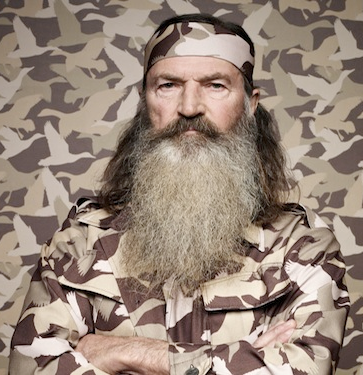

These reactions seem quite tame when compared to responses to Duck Dynasty star Phil Robertson’s recent comments on same sex behavior in an interview with GQ magazine. Robertson said, among other things:

These reactions seem quite tame when compared to responses to Duck Dynasty star Phil Robertson’s recent comments on same sex behavior in an interview with GQ magazine. Robertson said, among other things:

“Start with homosexual behavior and just morph out from there. Bestiality, sleeping around with this woman and that woman and that woman and those men,” he says. Then he paraphrases Corinthians: “Don’t be deceived. Neither the adulterers, the idolaters, the male prostitutes, the homosexual offenders, the greedy, the drunkards, the slanderers, the swindlers—they won’t inherit the kingdom of God. Don’t deceive yourself. It’s not right. (here)

The outcry was tremendous – condemnation from multiple corners. Robertson was even suspended from his own show (though it was reversed under pressure from conservative groups accusing the network—A&E—of attacking free speech and Christian values).

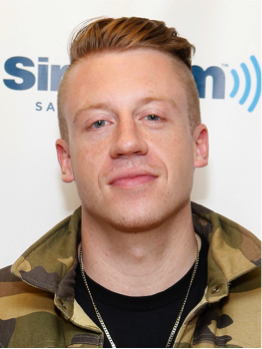

Now, setting aside the question about the logistics of suspending the bachelor from the show of which he is THE star, the differing responses seem to have a lot to do with intersections of class, region, religion and masculine styles. Certainly, Robertson’s sexual prejudice was more vehement, violent, graphic, and distasteful. Galavis—in fewer words and with a bit more caution—made some similar claims. But, Galavis failed to garner the backlash Robertson received (with a notable exception or two).

In an incredible piece about the reaction to Robertson, Mimi Schippers argues that the response reflected class bias and privilege:

“While I wholeheartedly and vociferously disagree with Robertson, I am also uncomfortable with how he is made to embody… the rural, poor, white redneck from the south that is racist, sexist, and homophobic. This isn’t just who he is; we’re getting a narrative told by the producers of Duck Dynasty and editors at GQ—extremely privileged people in key positions of power making decisions about what images are proliferated in the mainstream media… We are getting a carefully crafted representation of the rural, white, Southern, manly man, regardless of whether or not the man, Phil Robertson, is a bigot (which, it seems, he is).”

Schippers suggests that the controversy over Robertson performs a cultural sleight of hand whereby our disdain for him distracts us from “the structures of inequality that systematically serve the interests of wealthy, white, straight, and urban men who ultimately are the main benefactors of racism, sexism, and homophobia” (here). It inhibits institutional understandings of sexism, racism, classism and homophobia and scapegoats the least advantaged as responsible for perpetuating forms of inequality whose real beneficiaries are higher up the food chain.

This stands in contrast to an analysis of the Galavis controversy. He’s not a laughable, southern, rural, bigot; he’s a charming, sexy, doting father who we are supposed to adore, not laugh at. Indeed, even in his justification for why gay men shouldn’t be the stars of The Bachelor, he draws (in his revised statement) not on some sort of reactionary disgust for gay men, but on the welfare of children. He’s a dad, after all, and what he cares about is whether or not kids are being raised well. The questions he raises are ones raised by scholars and justices in recent court decisions about gay marriage: “Are the gays good parents/role models/caretakers for the kids?” In that sense, Galavis is positioned as a responsibly masculine man, one who puts his family’s welfare before his own.

Indeed, Galavis might represent what Melanie Heath calls “soft-boiled masculinity.” Gender and sexual inequality in this form of masculinity are not about enforcing patriarchy through some violent Old Testament edict (a la Robertson), but through particular understandings of family and wholesomeness. Similarly, Arlene Stein argues that there are new emergent forms of homophobia that might best be understood as reactions to feminist critiques of traditional masculinity. As Stein writes, “new forms of homophobia have emerged that are compatible with conservatives’ quest to be seen as compassionate protectors of the family” (here). While the style in which sexual prejudice is expressed and systems of inequality are perpetuated is dramatically different from Robertson’s brand of homophobia, perhaps the substance is not.

As such, Galavis’ homophobia is, perhaps, less easily recognized and more quickly forgiven because it is paired with being such an attentive father who cares so deeply about the wellbeing of his daughter. Yet, this is consistent with what Stein refers to as “neopatriarchal politics”—espousing sexual inequality under the guise of what’s good for kids.

Finally, as Galavis makes clear, his comments can show how individual friendship or support for civil rights for gays and lesbians can exist alongside stereotypes that work to re-marginalize these groups. It illuminates emergent homophobias and forms of sexual prejudice that may operate more subtly than previous forms, but continue to bolster some of the same structures of power and inequality.

________________________________________

*As Funny or Die’s The First Gay Bachelor video so entertainingly points out, a gay bachelor (or a lesbian bachelorette) would panic particular assumptions about gender and sexual desire upon which the entire show is based… But that’s a topic for another post.