Behold! Ladies and jellyspoons, allow me to present the mysterious object which has haunted my sociological brain for the past five weeks.

Can you spot the two lines in this drugstore receipt that made my brain make a sound like this?

I was so overjoyed to finally be able to buy my favorite toothpaste again, after almost 25 years, that I almost failed to notice that my cash register receipt stated the price of my two tubes of Oligodent (gout verveine) not only in euros, but in French francs–a currency that was supplanted by the euro more than 10 years ago.

The French were probably more aware of that transition than anyone else, because they minted the first euro coin in history, in May 1998! When the euro became the country’s official currency on the 1st of January 1999, the exchange rate was forever fixed at the rate shown on the receipt: 6.55957 francs to the euro. By now, that conversion ought to be old hat, right?

While it’s certainly considerate and pragmatic to provide “dual pricing” information during a period of transition–francs were accepted as legal tender in the French economy, in parallel with the euro, until January 2002–it’s a little surprising to see it still in use after a decade.

If they’re going to do that, I wondered, why not go all the way and show the value of a euro purchase in terms of the écu–the defining currency of France, which served her from the Middle Ages through the Enlightenment, from the reign of Louis IX (who minted the first écu in 1266) through that of Louis XVI (who lost his head in the Revolution of 1789)?

Some readers might be saying to themselves, “That’s an easy one: The French don’t print register receipts showing prices in écus because the last person who saw one has been dead for two hundred years–whereas there are lots of people alive right now who grew up using francs.”

Which raises an interesting and relevant point: decades after the Revolution and the establishment of francs as the national currency, the French–including people who probably never saw an écu in their lifetime–were still using the old currency as a reference point:

This took me back to the mid-1980s, when I spent my senior year of high school living with a French family, in which the parents still talked about prices in terms of “old” francs–a currency that had ceased to exist 25 years before! And today, living in Germany, it’s still very common to hear people talk about contemporary prices in terms of Deutsche marks, even though they went out of circulation over seven years ago, and you never see dual pricing (i.e., prices in both euros and marks) in stores or on receipts. People just do the math in their heads (clever people, those Germans).

It makes some sense for them to keep referring to marks, however, because their national bank (the Deutsche Bundesbank) has agreed to redeem marks for euros indefinitely: that is, should you happen to find a 100 mark note stashed away in a vintage purse, you can take it to any branch of the Deutsche Bundesbank worldwide and get it exchanged for euros, at the irrevocable rate of DM 1.95583 = one euro.

It’s not like that in France, however: the Banque de France stopped exchanging 100 franc notes for euros in February of this year, and will stop exchanging all other denominations of franc notes as of February 2012. (Pity the holders of the 12.4 million 100 franc notes that are still floating around unredeemed! And someone please inform the gentleman with 40 thousand French francs in his fridge.) This means that while the Deutsche mark will always have some exchange value, the French franc will soon be no more than a pretty piece of paper. Which makes the attempts by the French people to keep the franc alive through dual pricing even more puzzling.

Consider again the receipt that started this train of thought: the euro-to-franc currency conversion it shows was printed by a machine, purpose-built and programmed to perform that function. It bespeaks a kind of institutionalization process, which involves more than just remembering and talking about the franc, but literally embedding it in calculative devices. This might be an opportune moment to review W. Richard Scott’s definition of an institution:

Institutions are social structures that have attained a high degree of resilience. [They] are composed of cultural-cognitive, normative, and regulative elements that, together with associated activities and resources, provide stability and meaning to social life. Institutions are transmitted by various types of carriers, including symbolic systems, relational systems, routines, and artifacts (2001: 48).

“Resilience”? Check. “Stability and meaning”? Check. “Symbolic systems” and “artifacts”? Check and check.

That drugstore receipt is the product of the institutionalization of a currency system, which is in turn linked to national identity and a whole set of emotional and cognitive associations around what it means to be French–as distinct from being European. Lest you think that j’exagére un peu, let’s hear it from an Actual French Person™:

According to the original schedule [Franc] notes and coins were to be withdrawn in February 2002, and dual pricing in Francs and Euros would end at the beginning of the following year. The notes and coins duly disappeared more or less on schedule. Dual pricing should have disappeared by now, but the schedule has had to be revised under the pressure of popular opinion. Business who had already switched to pricing only in Euros have had to restart labelling prices in Francs as well. Too many people simply do not like the new currency.

…

In everyday conversation many people around here now operate three different systems depending on the value involved. For prices up to around €100 Euros are used. For higher values Francs are used – New Franc that is, except for values of 10,000 New Francs and more which are still quoted in old Francs. It is easy to sympathise with the old lady who echoed the complaint made when Britain decimalised in the 1970s: “I don’t know why they don’t wait until all us old people are dead before introducing this new money.”

That’s right: French people keep three parallel currency systems running in their head at any given time. As if that weren’t impressive enough, they also apply those price measurements selectively, based on the value of the item in question: the price of trifles can be expressed in euros, but something truly precious can only be priced in old (pre-1960) francs! This seems closely related to that classic status distinction among the rich: those who represent “old” money enjoy more prestige than the nouveaux riches, even if their net worth is identical to the penny.

There’s something complicated happening here, involving not just money and memory, but also status and value, in the broadest sense of the term. This is where sociology and anthropology really part ways with economics. While economists can acknowledge that there is more going on with currency than its material exchange value, they’re generally not interested in finding out what that “more” is (unless they can repackage sociology and anthropology as Freakonomics–which represents a whole disciplinary status war in its own right) because they don’t (yet?) have the means to shoehorn institutions and culture into tidy mathematical models.

Fortunately, sociologists and anthropologists are under no such obligation to force the messy, multi-faceted world of human behavior into the economists’ Procrustean bed. Many of us still do quantitative analyses, but our professional norms place far more value on empirical data than on elegant mathematical models.

If you’re interested in learning more about the differences between economics and economic sociology, this classic article is a good place to start. And for a fascinating visual representation of the geographical path of euros through France via trade with neighboring countries, click here.

* For those who have not already noticed, I feel obliged to point out that this title includes a bilingual pun. Thank you. Don’t forget to tip your waitress.

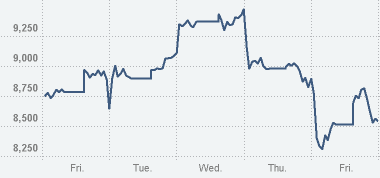

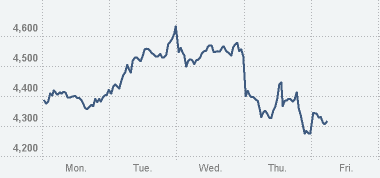

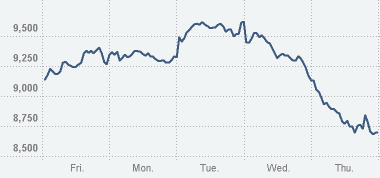

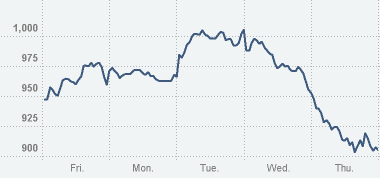

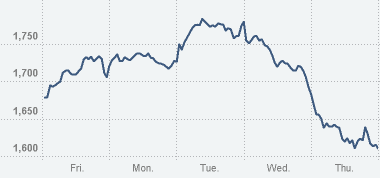

This one’s for all you crazy kids out there who said Sandy Weill’s experiment of creating a banking supermarket could never work, that its sheer size and the scale and multitude of services offered under a single roof were unsustainable, that no one management team or board of directors could possibly oversee its many arms.

This one’s for all you crazy kids out there who said Sandy Weill’s experiment of creating a banking supermarket could never work, that its sheer size and the scale and multitude of services offered under a single roof were unsustainable, that no one management team or board of directors could possibly oversee its many arms.