Welcome to the fourth and final installment to my series on the history of the Quantified Self. If you’re just joining us, be sure to review parts one, two, and three, wherein I introduced and explored a project that seeks to build a genealogical relationship between an already analogous pair: eugenics and the contemporary Quantified Self movement. The last two posts appear to have, at best, complicated, and at worst, failed the hypothesis: critical breaks along both of the genealogies elucidated within each post seem more like chasms which make eugenics and QS difficult to connect in a meaningful way. At the root of this break seems to be the fundamental tenets underlying each movement. Eugenics, with its emphasis on hereditarily passed physical and psychological traits, precludes the possibility that outside, environmental influences may lead to changes in an individual’s bodily or mental makeup. The Quantified Self, on the other hand, is predicated on the belief that, by tracking the variables associated with one’s activities or environment, one might be able to make adjustments to achieve physical or psychological health. On the surface, then, there is an incommensurability between the two fields. However, by understanding how the technologies of the two movements work in the context of the predominant form of Foucauldian governmentality and biopower of their respective times, we may be able to resolve this chasm. more...

history of qs

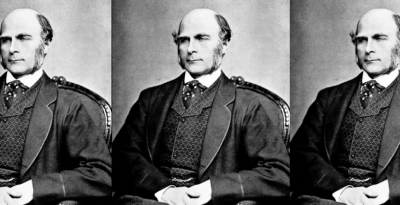

Welcome to part three of my multi-part series on the history of the Quantified Self as a genealogical ancestor of eugenics. In last week’s post, I elucidated Francis Galton’s influence on experimental psychology, arguing that it was, largely, a technological one. In an oft-cited paper from 2013, researcher Melanie Swan argues that “the idea of aggregated data from multiple…self-trackers[, who] share and work collaboratively with their data” will help make that data more valuable—be it to the individual tracking, physician working with them, corporation selling the device worn, or other stakeholder (86). No doubt, then, the value of the predictive power of correlation and regression to these trackers. Harvey Goldstein, in a paper tracing Galton’s contributions to psychometrics, notes that Galton was not the only late-nineteenth century scientist to believe that genius was passed hereditarily. He was, however, one of the few to take up the task of designing a study to show genealogical causality regarding character, thanks once again to his correlation coefficient and resultant laws of regression. more...

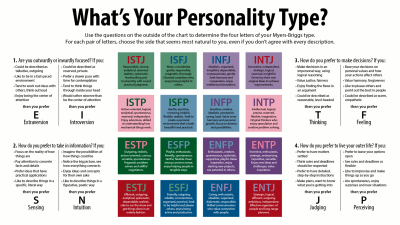

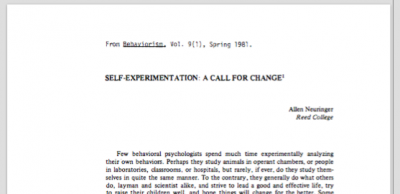

Last week, I began an attempt at tracing a genealogical relationship between eugenics and the Quantified Self. I reviewed the history of eugenics and the ways in which statistics, anthropometrics, and psychometrics influenced the pseudoscience. This week, I’d like to begin to trace backwards from QS and towards eugenics. Let me begin, as I did last week, with something quite obvious: the Quantified Self has a great deal to do with one’s self. Stating this, however, helps place QS in a historical context that will prove fruitful in the overall task at hand. more...

In the past few months, I’ve posted about two works of long-form scholarship on the Quantified Self: Debora Lupton’s The Quantified Self and Gina Neff and Dawn Nufus’s Self-Tracking. Neff recently edited a volume of essays on QS (Quantified: Biosensing Technologies in Everyday Life, MIT 2016), but I’d like to take a not-so-brief break from reviewing books to address an issue that has been on my mind recently. Most texts that I read about the Quantified Self (be they traditional scholarship or more informal) refer to a meeting in 2007 at the house of Kevin Kelly for the official start to the QS movement. And while, yes, the name “Quantified Self” was coined by Kelly and his colleague Gary Wolf (the former founded Wired, the latter was an editor for the magazine), the practice of self-tracking obviously goes back much further than 10 years. Still, most historical references to the practice often point to Sanctorius of Padua, who, per an oft-cited study by consultant Melanie Swan, “studied energy expenditure in living systems by tracking his weight versus food intake and elimination for 30 years in the 16th century.” Neff and Nufus cite Benjamin Franklin’s practice of keeping a daily record of his time use. These anecdotal histories, however, don’t give us much in terms of understanding what a history of the Quantified Self is actually a history of. more...

Welcome to part three of my multi-part series on the history of the Quantified Self as a genealogical ancestor of eugenics. In last week’s post, I elucidated Francis Galton’s influence on experimental psychology, arguing that it was, largely, a technological one. In an oft-cited paper from 2013, researcher Melanie Swan argues that “the idea of aggregated data from multiple…self-trackers[, who] share and work collaboratively with their data” will help make that data more valuable—be it to the individual tracking, physician working with them, corporation selling the device worn, or other stakeholder (86). No doubt, then, the value of the predictive power of correlation and regression to these trackers. Harvey Goldstein, in a paper tracing Galton’s contributions to psychometrics, notes that Galton was not the only late-nineteenth century scientist to believe that genius was passed hereditarily. He was, however, one of the few to take up the task of designing a study to show genealogical causality regarding character, thanks once again to his correlation coefficient and resultant laws of regression. more...

Last week, I began an attempt at tracing a genealogical relationship between eugenics and the Quantified Self. I reviewed the history of eugenics and the ways in which statistics, anthropometrics, and psychometrics influenced the pseudoscience. This week, I’d like to begin to trace backwards from QS and towards eugenics. Let me begin, as I did last week, with something quite obvious: the Quantified Self has a great deal to do with one’s self. Stating this, however, helps place QS in a historical context that will prove fruitful in the overall task at hand. more...

In the past few months, I’ve posted about two works of long-form scholarship on the Quantified Self: Debora Lupton’s The Quantified Self and Gina Neff and Dawn Nufus’s Self-Tracking. Neff recently edited a volume of essays on QS (Quantified: Biosensing Technologies in Everyday Life, MIT 2016), but I’d like to take a not-so-brief break from reviewing books to address an issue that has been on my mind recently. Most texts that I read about the Quantified Self (be they traditional scholarship or more informal) refer to a meeting in 2007 at the house of Kevin Kelly for the official start to the QS movement. And while, yes, the name “Quantified Self” was coined by Kelly and his colleague Gary Wolf (the former founded Wired, the latter was an editor for the magazine), the practice of self-tracking obviously goes back much further than 10 years. Still, most historical references to the practice often point to Sanctorius of Padua, who, per an oft-cited study by consultant Melanie Swan, “studied energy expenditure in living systems by tracking his weight versus food intake and elimination for 30 years in the 16th century.” Neff and Nufus cite Benjamin Franklin’s practice of keeping a daily record of his time use. These anecdotal histories, however, don’t give us much in terms of understanding what a history of the Quantified Self is actually a history of. more...