I’ve been thinking on and off since mid-summer about a hole I’ve identified in our collective theorizing of augmented reality. To illustrate it, imagine the following conversation:

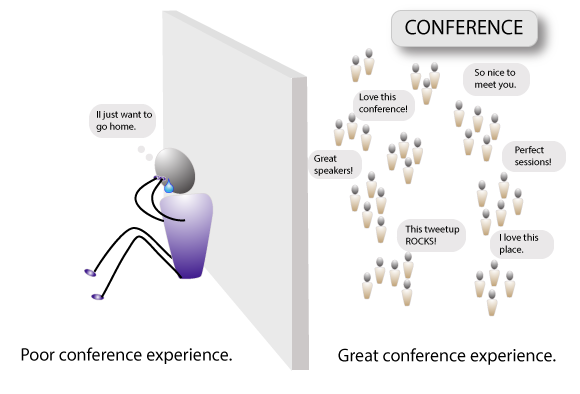

Digital Dualist: ‘Online’ and ‘offline’ are two distinct, separate worlds!

Me: That’s not true. ‘Online’ and ‘offline’ are part of the same augmented reality.

Digital Dualist: Are you saying that ‘online’ and ‘offline’ are the same thing?

Me: No, of course not. Atoms and bits have different properties, but both are still part of the same world.

Digital Dualist: So ‘online’ and ‘offline’ are different, but not different worlds?

Me: Correct.

Digital Dualist: But if they’re not different worlds, then what kind of different thing are they?

Me: …

I don’t know about you, but this is where I get stuck.