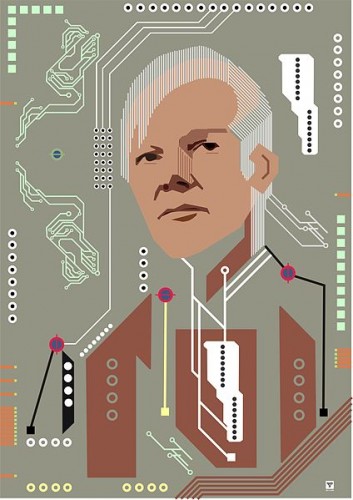

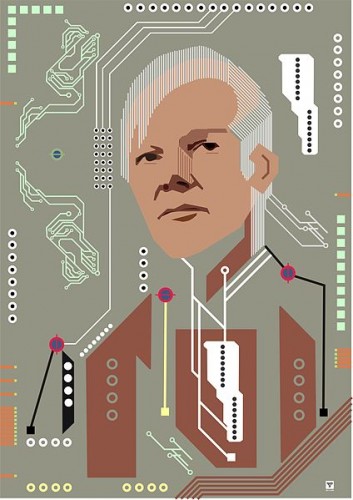

Julian Assange, the notorious founder and director of WikiLeaks, is many things to many people: hero, terrorist, figurehead, megalomaniac. What is it about Assange that makes him both so resonant and so divisive in our culture? What, exactly, does Assange stand for? In this post, I explore two possible frameworks for understanding Assange and, more broadly, the WikiLeaks agenda. These frameworks are: cyber-libertarianism and cyber-anarchism.

First, of course, we have to define these two terms. Cyber-libertarianism is a well-established political ideology that has its roots equally in the Internet’s early hacker culture and in American libertarianism. From hacker culture, it inherited a general antagonism to any form of regulation, censorship, or other barrier that might stand in the way of “free” (i.e., unhindered) access of the World Wide Web. From American libertarianism it inherited a general belief that voluntary associations are more effective in promoting freedom than government (the US Libertarian Party‘s motto is “maximum freedom, minimum government”). American libertarianism is distinct from other incarnations of libertarianism in that tends to celebrate the market and private business over co-opts or other modes of collective organization. In this sense, American libertarianism is deeply pro-capitalist. Thus, when we hear the slogan “information wants to be” that is widely associated with cyber-libertarianism, we should not read it as meaning gratis (i.e., zero price); rather, we should read it as meaning libre (without obstacles or restrictions). This is important because the latter interpretation is compatible with free market economics, unlike the former.

Cyber-anarchism is a far less widely used term. In practice, commentators often fail to distinguish between cyber-anarchism and cyber-libertarianism. However, there are subtle distinctions between the two. Anarchism aims at the abolition of hierarchy. Like libertarians, anarchists have a strong skepticism of government, particularly government’s exclusive claim to use force against other actors. Yet, while libertarians tend to focus on the market as a mechanism for rewarding individual achievement, anarchists tend to see it as means for perpetuating inequality. Thus, cyber-anarchists tend to be as much against private consolidation of Internet infrastructure as they are against government interference. While cyber-libertarians have, historically, viewed the Internet as an unregulated space where good ideas and the most clever entrepreneurs are free to rise to the top, cyber-anarchists see the Internet as a means of working around and, ultimately, tearing down old hierarchies. Thus, what differentiates cyber-anarchist from cyber-libertarians, then, is that cyber-libertarians embrace fluid, meritocratic hierarchies (which are believed to be best served by markets), while anarchists are distrustful of all hierarchies. This would explain while libertarians tend to organize into conventional political parties, while the notion of an anarchist party seems almost oxymoronic. Another way to understand this difference is in how each group defines freedom: Freedom for libertarians is freedom to individually prosper, while freedom for anarchists is freedom from systemic inequalities. more...

Image of the week is Julian Assange at Occupy London dressed as a Jedi.

Image of the week is Julian Assange at Occupy London dressed as a Jedi.