For a novelist, the route to publication is frequently strange and even more frequently frustrating. For me, one of those frustrations has been really frustrating because I get the distinct sense that I shouldn’t even feel that way.

For a novelist, the route to publication is frequently strange and even more frequently frustrating. For me, one of those frustrations has been really frustrating because I get the distinct sense that I shouldn’t even feel that way.

Stop me if you’ve heard one of these before: “[something online/digital] is super-awesome because it’s ‘open’—anyone can participate! Our cool [product/app/service] allows people to [action] all by themselves, without going through [older gatekeeper/channel/service provider]! Our [product/app/service] is totally going to [democratize/revolutionize/‘be a game changer for’] the world of [action]-ing, because now anyone can [action]!” The tl;dr here is that “openness” undermines existing power structures and institutions, and that this opened or leveled playing field allows individuals both to take new autonomous, self-directed actions and to collaborate with each other in new ways.

This isn’t the whole story, however, nor do most “open” initiatives really play out that way. Zeynep Tufekci (@techsoc) does a great job of explaining how “flat” or “horizontal” networks evolve into hierarchical structures “not in spite of, but because of, their initial open nature.” Tufekci makes her argument in the context of examining the “leaderless” revolutions of the Arab Spring; Wessel van Rensburg (@wildebees) draws on Tufekci & others to situate this kind of optimism about “openness” in the broader context of early Silicon Valley and technoutopianism. I’m now going to provide a case study of openness’s utopian promise gone awry with a much more banal example: Craigslist, and four of my own experiences apartment hunting in the Boston area between 1999 and 2013. more...

This Christmas, we got my father-in-law an iPad. He’s basically never used a computer before now.

I knew that watching him start to get acquainted with it would highlight some interesting stuff. What I didn’t expect was exactly what stuff that would be. He’s been struggling to get the hang of it, of course – though he’s doing much better than he thinks he is – but one of the things that my husband and I have struggled with as we (mostly he) play periodic tech support is in getting my father-in-law to understand that he should learn by trying, that the device itself really is pretty much impossible for him to break, short of dropping it. That he shouldn’t be afraid of experimenting.

Or: Lots of Words But Then An Awesome GIF, So Hang In There

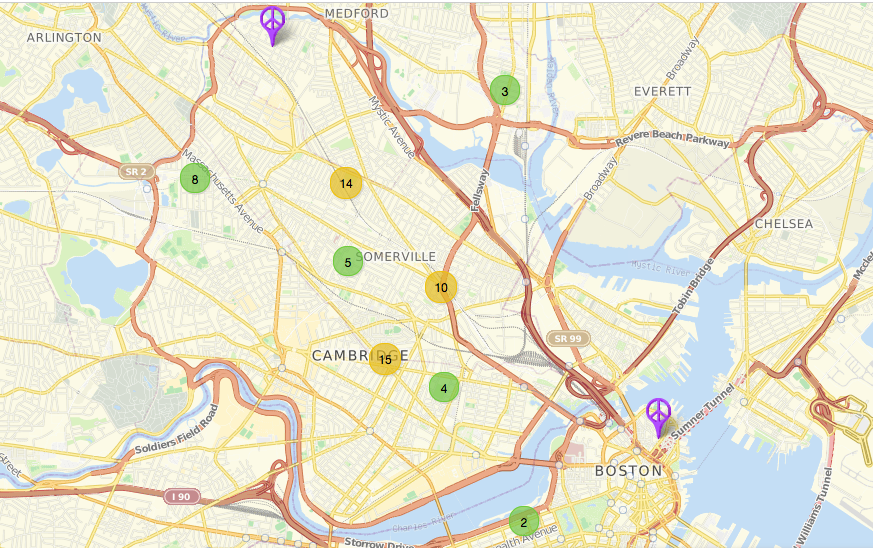

Operating an automobile in an urban area is often quite frustrating. When you want to be driving, you’re often parked in traffic; when you want to be parked, you’re often driving around for a spot. Of course, there are apps for that: real-time traffic mapping apps from Google and others, and now we are also seeing so-called “smart parking” apps that display open parking spots by way of small sensors built in or near the parking space itself, fed into a network and then to a smartphone screen. A recent New York Times story on “smart parking” states that, more...

Science and Technology studies scholars have long understood that the physical structures and architectures of everyday life both reflect and construct human values, propensities, lines of action, and behavioral and social constraints. This was famously described by Langdon Winner with regards to the segregationist role of Robert Moses’ low bridges on the New York highway system. Recently on this blog, David Banks (@DA_Banks) wrote a beautiful essay on the technology, and technological artifacts of Troy New York. Indeed, the architectures of spaces in which we move shape how we move and reflect normative expectations about how we ought to move. more...

When something that is not originally digital is converted to digital form, that thing has been “digitized”—but what do you call it when something that is digital is converted to analogue or material form? There was a discussion to this effect in my Twitter feed a few months ago, but I don’t recall that we ever came to consensus about a) whether there is a term for this, and if not, b) what that term should be.

When something that is not originally digital is converted to digital form, that thing has been “digitized”—but what do you call it when something that is digital is converted to analogue or material form? There was a discussion to this effect in my Twitter feed a few months ago, but I don’t recall that we ever came to consensus about a) whether there is a term for this, and if not, b) what that term should be.

Whatever that term is or may be, it’s a term that I keep needing, so I’m hoping to identify it by reopening the discussion here. Without further ado, here are some of the recent digital/analogue crossovers that have inspired my question:

(This is the full version of a two-part essay that I posted in October of this year. Here are links to Part I and Part II)

“Well, you saw what I posted on Facebook, right?”

I don’t know about you, but when I get this question from a friend, my answer is usually “no.” No, I don’t see everything my friends post on Facebook—not even the 25 or so people I make a regular effort to keep up with on Facebook, and not even the subset of friends I count as family. I don’t see everything most of my friends tweet, either; in fact, “update Twitter lists” has been hovering in the middle of my to-do list for the better part of a year. And even after I update those lists, I probably still won’t be able to keep up with everything every friend says on Twitter, either.

I feel guilty when I get the “You saw what I posted, right?” question. I feel like a bad friend, like I’m slacking off in my care work, like I’m failing to value my important human relationships. Danah boyd (@zephoria) was talking about something similar in October of this year at “Boom and Bust“—about how social networking sites create pressure to put time and effort into tending weak ties, and how it can be impossible to keep up with them all. Personally, I also find it difficult to keep up with my strong ties. I’m a great “pick up where we left off” friend, as are most of the people closest to me (makes sense, right?). I’m decidedly sub-awesome, however, at being in constant contact with more than a few people at a time. more...

In light of the recent tragedy in Newtown, Connecticut, the debate over access to firearms has again been thrust to the fore of our national consciousness. With the resurgence of this debate, the classic “guns don’t kill people” line of argument will inevitably feature prominently in radio conversations, TV interviews, Facebook posts, and tweets. The “guns don’t kill people” trope is part of a larger pattern in how our society frames the relationship between technology and (lack of) collective responsibility.

In light of the recent tragedy in Newtown, Connecticut, the debate over access to firearms has again been thrust to the fore of our national consciousness. With the resurgence of this debate, the classic “guns don’t kill people” line of argument will inevitably feature prominently in radio conversations, TV interviews, Facebook posts, and tweets. The “guns don’t kill people” trope is part of a larger pattern in how our society frames the relationship between technology and (lack of) collective responsibility.

“Guns don’t kill people” is a spin on the broader “technology is neutral” trope–still widely-embraced by Silicon Valley–whose function is to absolve the creators of technology from any responsibility for the consequences of what they have designed. The “technology is neutral” trope has long be subject to criticism. From Frankenstein’s monster turning on its creator to Robert Oppenheimer’s own reflections on creating the bomb, Western civilization has wrestled with the question of where responsibility resides in atrocities facilitated by technology, and we, on occasion, are reminded that the choice of what to research and create (or to not research and not create) is an expression of both individual and cultural values. As the great sociologist Max Weber once said, only through “naive self-deception” does a technician ignore “the evaluative ideas with which he unconsciously approaches his subject matter… that he has selected from an absolute infinity a tiny portion with the study of which he concerns himself.” Technology is never neutral because its birth–its very existence–is the product of both political forces and values-oriented decision making.

The following post was originally a seminar “reading response” paper that I had a little too much fun with. Reproduced here for your (possible) amusement:

Oh, technoutopianism. I came of age steeped in you; I was the fish, and you were the water that surrounded me and kept me wet. We were once such intimate familiars—and yet, you still managed to smack me right upside the head when I moved to the Bay Area.

It’s not that we weren’t great together, for a time. more...