Google Earth software [creates] a more realistic world that blurs the line between virtual life and reality and helps make the program look more like a variation of the Star Trek Holodeck.

Via.

Google Earth software [creates] a more realistic world that blurs the line between virtual life and reality and helps make the program look more like a variation of the Star Trek Holodeck.

Via.

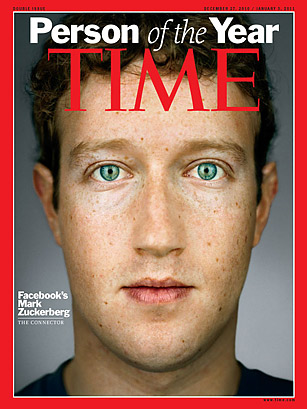

The premise of this blog is that technology is fundamental to our selves, lives and all of reality. And this point is best exemplified by Facebook. The site’s founder and CEO is TIME magazine’s 2010 Person of the Year. Is this the correct choice? Perhaps Julian Assange? Donna Haraway, anyone?

“African-American and Latino adults in the US who use the internet are twice as likely as whites to use the website Twitter.” [Note: it might be best to strike the words “the website” from that sentence since many access the service using other sites and mobile applications.]

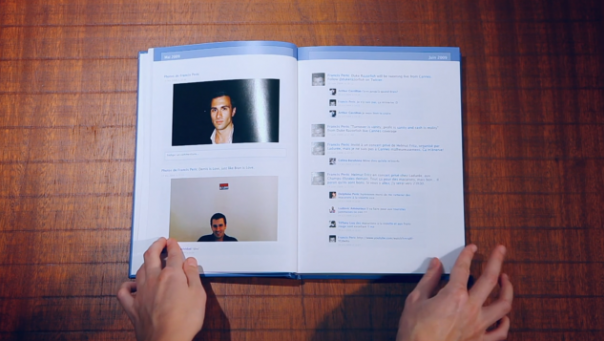

Many worry about the immortality of our behavior on social network sites like Facebook. Regrettable behaviors can become Facebook Skeletons in your digital closet. However, I have argued before that what is equally true is that our online presence is extremely ephemeral. Status updates speed by, perhaps delighting us in the moment, but are quickly forgotton. The innundation of photographs of yourself and others is so heavy that particular moments often become lost in the flow. Our digital content may live forever, but it does so in relative obscurity. Just try searching for that witty status update your friend made on Facebook last month. It is this ephemerality of our online social lives that makes this art/design project by Siavosh Zabeti so interesting. When our Facebook lives are placed in a book, our socialization grasps at the tactile permanence of the physical.

When Facebook becomes a book from Siavosh Zabeti on Vimeo.

If books like this became popular, would we create our Facebook presence any differently given this new, more physical medium?

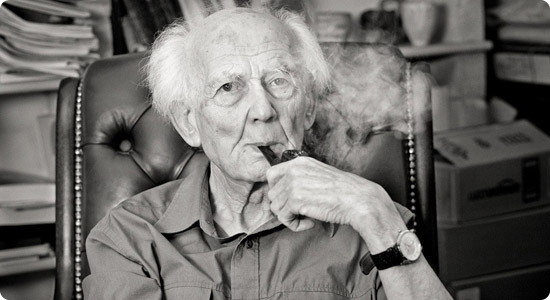

Zygmunt Bauman has famously conceptualized modern society as increasingly “liquid.” Information, objects, people and even places can more easily flow around time and space. Old “solid” structures are melting away in favor of faster and more nimble fluids. I’ve previously described how capitalism in the West has become more liquid by moving out of “solid” brick-and-mortar factories making “heavy” manufacturing goods and into a lighter, perhaps even “weightless,” form of capitalism surrounding informational products. The point of this post is that as information becomes increasingly liquid, it leaks.

Zygmunt Bauman has famously conceptualized modern society as increasingly “liquid.” Information, objects, people and even places can more easily flow around time and space. Old “solid” structures are melting away in favor of faster and more nimble fluids. I’ve previously described how capitalism in the West has become more liquid by moving out of “solid” brick-and-mortar factories making “heavy” manufacturing goods and into a lighter, perhaps even “weightless,” form of capitalism surrounding informational products. The point of this post is that as information becomes increasingly liquid, it leaks.

WikiLeaks is a prime example of this. Note that the logo is literally a liquid world. While the leaking of classified documents is not new (think: the Pentagon Papers), the magnitude of what is being released is unprecedented. The leaked war-logs from Afghanistan and Iraq proved to be shocking. The most current leaks surround US diplomacy. We learned that the Saudi’s favored bombing Iran, China seems to be turning on North Korea, the Pentagon targeted refugee camps for bombing and so on. And none of this would have happened without the great liquefiers: digitality and Internet.

These technologies create information that is more liquid and leak-able and have also allowed WikiLeaks to become highly liquid itself. It is not just one website, but also flows throughout the web on its many “mirror” sites. The data is disseminated over peer-to-peer (P2P) networks making it truly “the new Napster.” And just as shutting down Napster did not end music-sharing, shutting down WikiLeaks will not end the sharing of classified information.

But what are the consequences of this new politics of liquidity?

The early days of the public Internet saw the emergence of a “hacker” culture that eventually turned more explicitly political from the 1980’s through the 90’s into what has come to be known as “cyberlibertarianism.” What defines this movement is the belief that information should be free, a stance clearly shared by WikiLeaks renegade editor-in-chief, Julian Assange (who is on the cover of the next Time magazine).

Assange’s goal is to end government secrecy. And he acknowledges that the government response to WikiLeaks will be to become more secret. And that, perhaps counter-intuitively, is exactly the point. As Assange states (via),

in a world where leaking is easy, secretive or unjust systems are nonlinearly hit relative to open, just systems

This argument made by Assange is similar to an argument made by George Ritzer. Using Bauman’s terms, Ritzer argues that old, heavy structures need to become more porous else they will be washed away in the wave of liquidity. Assange’s strategy is exactly to make the U.S. government more secretive and therefore less porous. Thus, the government will be less effective at communicating both internally and diplomatically with others – what Assange calls the “secrecy tax.”

This argument made by Assange is similar to an argument made by George Ritzer. Using Bauman’s terms, Ritzer argues that old, heavy structures need to become more porous else they will be washed away in the wave of liquidity. Assange’s strategy is exactly to make the U.S. government more secretive and therefore less porous. Thus, the government will be less effective at communicating both internally and diplomatically with others – what Assange calls the “secrecy tax.”

The history of the Internet will be, in part, its role in creating an increasingly liquid world, and WikiLeaks will come to be as important (or more) than Napster in this regard. Aside from if one is for or against WikiLeaks, we should ask: Is Bauman correct? Will the U.S. government come to be harmed by becoming increasingly solid, heavy and out-of-date in the face of the modern torrent of liquidity?

Apple “fan” and former employee Michael Tompert created a series of photographs depicting destroyed Apple products. Why do many find these images so striking?

Besides being beautiful deconstructions in themselves, these obliterated Apple products force us to come face to face with our love of sleekly designed magic-like devices. We might feel a tinge of horror seeing something we love so brutally and carelessly destroyed to the point of uselessness. Perhaps we have grown empathetically and intimately attached to these devices, bonding with them by day in our pockets and by night at our bedsides.

Alternatively, and moving from love to hate, perhaps they serve as a sort of catharsis by symbolizing our anger at the spectacle of consumer culture in general, and more specifically, Apple’s own quasi-religious Disney-like image. [a previous post on Apple-as-spectacle in response to the unveiling of the iPad]

Or maybe the images take on a subversive quality in that they bring attention to the complex and chaotic inner-workings of these devices – precisely what Apple has worked so hard to conceal in order to give the devices their “magic” quality.

Maybe the images force us to recognize the contradiction inherent in the disposability of things we spend so much money on?

Other ideas?

This Economist blog compares Wikileaks to Facebook as part of a broader trend towards transparency throughout society.

This Economist blog compares Wikileaks to Facebook as part of a broader trend towards transparency throughout society.

There are echoes here of Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg’s famously aggressive position that society is evolving towards more transparency and less privacy (a belief which is certainly convenient for a social-networking site that wants to be able to sell users’ data). Maybe it’s something about tech geeks, or maybe it’s just related to the self-interest of people and organisations whose particular strength lies in an ability to get a hold of other people’s information. But it definitely seems like we’re learning a lesson here: while information may want to be free, human beings are usually better off when it’s on a leash.

Additionally, this New York Times story summarizes the Wikileaks issue.

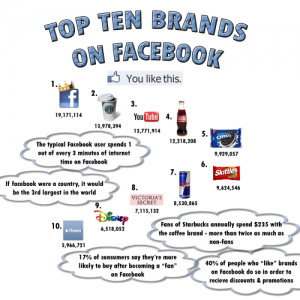

Advertising on social media is more than those segregated paid-for-spaces that display ads paid for by companies (e.g., on the far-right of your Facebook screen). This sort of paid-advertising has been shown to be so highly ineffective that some have predicted it will be the downfall of the social web. However, these predictions do not understand that the fundamental point of the social web (2.0) is that users are prosumers; they are simultaneously both consumers and producers of content. And advertising is no different. Advertisements that we simply consume worked in a consumer medium, like television. However, social media is a prosumer medium, and today we are the ones doing the advertising work of integrating corporate logos and branding into our profiles and news feeds.

Advertising on social media is more than those segregated paid-for-spaces that display ads paid for by companies (e.g., on the far-right of your Facebook screen). This sort of paid-advertising has been shown to be so highly ineffective that some have predicted it will be the downfall of the social web. However, these predictions do not understand that the fundamental point of the social web (2.0) is that users are prosumers; they are simultaneously both consumers and producers of content. And advertising is no different. Advertisements that we simply consume worked in a consumer medium, like television. However, social media is a prosumer medium, and today we are the ones doing the advertising work of integrating corporate logos and branding into our profiles and news feeds.

Facebook’s ubiquitous “like” button reflects our modern task of self-presentation (and distinction) based on our taste in just about anything and everything, documented and compared to the various “likes” of any other visitor to your profile (and remember: what someone “likes” may not be what they actually like but what they want others to see that they like). In modern consumer culture, this collection of displayed “likes” will include corporate brands that one identifies with. This might mean clicking “like” on the Starbucks or Victoria’s Secret pages, which then becomes a part of your profile.

Advertising also becomes woven into the news stream -that digital flow of sociality that has become the nexus of public sociality on the site. Marketers have always viewed friend-recommendations as the holy grail of advertising: If someone you know and trust recommends or is simply associated with a product then you are much more likely to have a favorable opinion of and perhaps consume that product. Facebook helps brands to achieve just this using tactics more clever than just the “like” button. For instance, many of us have seen advertisements that give you, say, 10% off of something if you create a Facebook status update or a tweet about the product or service. Many of us have noticed these status updates in our Facebook friend stream or Twitter feed. These are more than just commercials, but are statements by people we know and perhaps even respect.

This is prosumer advertising: we are both the producers and consumers of advertising messages (similar to wearing a hat with the “Nike” logo on it). Social media is built on prosumer labor (what would Facebook be without our efforts?) and paid for by advertising, so it makes complete sense that this advertising will be of the prosumer sort. Will we continue to see more new ways in which we turn ourselves and our socialization into various advertisements?

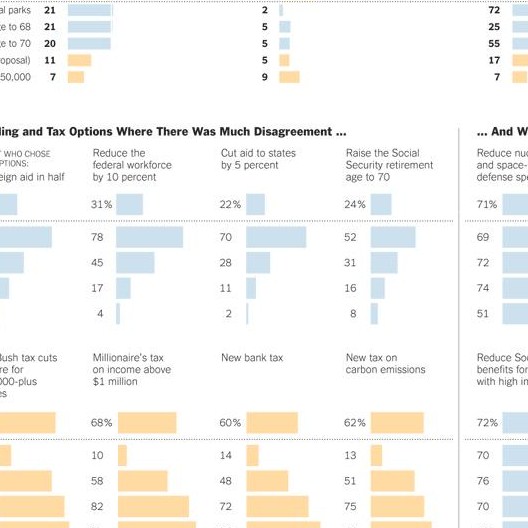

The New York Times asked their readers how to balance the federal budget. Click the image below to see how the 7000 replies via Twitter panned out [article | methodology].

If Web 2.0 tools are all about “democratization“, how might democracies utilize the crowd using Web 2.0 tools? We’ve spoken about how user-generated content makes us all “prosumers” of the web, that is, we are both producers and consumers of content. Isn’t democracy inherently a prosumer form of politics where we are (hypothetically) both the producers and consumers of political decisions?

In the future, we will all probably have some Facebook skeletons. They might be regrettable pictures in various states of inebriation and/or undress, unfortunate status updates, etc. I’ve argued that the media has overblown these risks because, as the digital dirt on our collective hands becomes more commonplace, the stigma it carries will erode. However, the 2010 midterm elections in the United States suggest a point that I previously neglected: the stigmatization of digital dirt may be eroding, but eroding for whom?

In the future, we will all probably have some Facebook skeletons. They might be regrettable pictures in various states of inebriation and/or undress, unfortunate status updates, etc. I’ve argued that the media has overblown these risks because, as the digital dirt on our collective hands becomes more commonplace, the stigma it carries will erode. However, the 2010 midterm elections in the United States suggest a point that I previously neglected: the stigmatization of digital dirt may be eroding, but eroding for whom?

It seems clear that the acceptance of a little digital dirt is occurring much faster for men than for women. And, what the 2010 elections made clear is that there is a double standard for women to keep a perfect online presence, while men are more easily forgiven.

Political campaigns have always struggled against the skeletons in a candidate’s closet. And this will increasingly involve photos uploaded to sites like Facebook and Twitter. Younger individuals who have been using these services for years are starting to run for increasingly important political offices, and those older have started using social media in large numbers. Thus, the impact of one’s Facebook presence on important political campaigns is not a worry for the future, but is upon us now.

The New York Times outlines some cases from the 2010 midterm elections and asks if voters will tolerate leaders in various states of undress and inebriation? The answer is probably yes, but for men first.

For instance, Sean Duffy won a seat in congress after appearing on The Real World – the MTV reality show that foreshadowed the Facebook norm of documenting your everyday life as if you were a celebrity. Duffy’s indiscretions were fully documented and brought up during the campaign. It proved to be a non-issue. He won.

Conversely, when revealing photos of a female candidate surface, it becomes national news. Krystal Ball, who was also running for congress, became one of the most Googled persons in the world when pictures of her at 22 years old dressed in a skimpy Halloween costume hit the Internet. The obsession with her body and her indiscretions came to define her and her campaign. She lost.

Society has to accept that women of my generation have sexual lives that are going to leak into the public sphere. Sooner or later, this is a reality that has to be faced, or many young women in my generation will not be able to run for office.

What we do not want is for women growing up today to be reluctant to run for office because every picture of them wearing a short skirt at a Halloween party will become the most Googled image in the world.

So, yes, we may be increasingly forgiven for past indiscretions when we all have some of them documented for the word to see. But will this forgiveness be equal for all?