A couple of months back, I wrote about an informal meeting of the Cyborgology Crew in which we began to hash out some of the vocabulary issues that currently muddle up theorizing about technology and society. In that post, I interrogated the words “online” and “offline.” This online/offline discussion took up the better part of our day. A second issue also arose, however, and this was one that we never fully resolved. With bellies full of pizza and leg-shaking levels of caffeine, we duked it out over the term “physical co-presence.” Today, I want to put forth our (mostly?) agreed upon critique of the term physical co-presence, and offer an alternative which, on the day of the meeting, I probably articulated poorly. Like the interrogation of online and offline, this is far from a definitive statement. Rather, it is a starting point and a widespread invitation for critique, suggestions, and participation in the construction of a useful theoretical vocabulary.

A Critique of Physical Co-Presence

Physical co-presence refers to two or more bodies sharing the same physical space at the same time. People typically use this term in juxtaposition to all other mediated forms of interaction. For example, let’s say two people are collaborating on a project[i]. They may exchange drafts via email, talk through ideas via Skype, link relevant articles to on another via Twitter, and/or get together in a coffee shop to hammer out details. Only the coffee shop qualifies as physical co-presence, whereas Skype, Twitter, and email are otherwise mediated.

To give credit where credit is due, physical co-presence is more accurate than its synonym, Face to Face (FtF), which ignores the capabilities of video chat. Physical co-presence, however, suffers its own muddling effects. The language of “physical” is particularly problematic. It implies that digitally and electronically mediated communication exhibit a relative dearth of physicality as compared to conditions in which interactants’ bodies share the same space at the same time. This is far from the case.

All forms of mediated interaction—both synchronic and asynchronic— can be intensely physical. Let us go back to the mundane example of project partners. Imagine that they get into a heated argument via telephone about the direction of the project. They may both feel knots in their stomachs, their cheeks may get hot, their shoulders tense, their nails may dig painfully into their palms. I’m certain if you use your imaginations, you creative readers can think of several other kinds of very physical encounters that take place through digital and/or electronic mediation. Juxtaposing physical co-presence to other forms of interaction, then, creates a false distinction centered around physicality.

And yet, there is a reason that the Cyborgology Team made the effort to share physical space as we hashed out these questions of vocabulary. We communicate via email and text message quite regularly, and certainly could have arranged a group video chat which would have been less expensive and more convenient for all involved. We all agreed, however, that it was important, in this case, to share the same physical space. Similarly, people travel to visit loved ones, pay to attend concerts, and wince at the challenge of “long distance” relationships. Theoretically, this indicates that there *is* something distinct about bodies in the same space, but physical co-presence fails to capture the properties of this distinction with adequate subtlety.

Sensory Co-Presence:

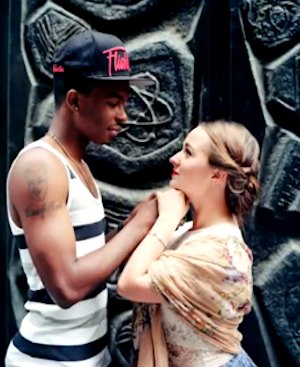

I argue that sensory co-presence more accurately captures the distinct properties of shared physical and temporal space. By sensory co-presence I mean bodies in the same space, at the same time. These bodies breath the same air, feel the same sun, see the same moon, are touched by the same breeze. Sensory co-presence makes no assumptions about the level of physicality. Rather, it, like all platforms of interaction, maintains a particular set of affordances. The distinguishing affordance of sensory co-presences is that all actors involved are subject to the same sensory stimuli. Again, I reiterate, sensory co-present interaction is not the pinnacle of shared physical experience, with other mediated forms—computers, mobile devices, telephones, or tin cans—offering the next best thing. Rather, each medium contains affordances all its own, with varying effects upon physicality under an array of conditions.

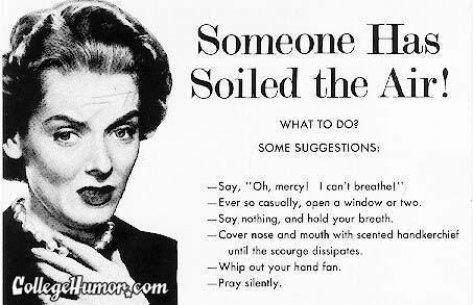

Indeed, physicality is always continual and non-linear. All interaction is mediated. The platform of mediation affords different levels, and different kinds, of shared physical and sensory experience. For example, a telephone conversation is more auditory than it is visual, tactical, or olfactory. However, these other senses are not entirely excluded. The look of the phone and visual stimulus of an alert to an incoming call, including a name, phone number, icon, and/or personal image; The smell of one’s own breath against worn plastic; The heat of the phone against a red ear, or weight of the phone in the palm of a tired hand, all contribute to the experience of a telephonically mediated conversation. However, in emphasizing sound, this particular medium minimizes—though again, does not eliminate— sight, smell, and touch. In doing so, sensory sound experiences are sharper, such that shrill noises may elicit pain while rhythmic erotic panting elicits waves of bodily pleasure. Moreover, the absence of sensory co-presence can force interactants to more acutely attune to physical experiences, intensifying their bodily effects. Returning to the project partners, imagine that during an encounter, mediated by, let’s say, Skype, one partner notices a putrid smell wafting through hir office window. Were the interactants sensorily co-present, they would both experience the scent (though perhaps to different degrees depending on their respective nasal-passage biologies), which may become a key nexus of the interaction, or alternatively, fade unnoticed among the infinite array of sensory stimuli in their midst. Because they are engaged via Skype, however, partner B only learns about the smell via the accounts of partner A. If partner A gives a particularly detailed account, the physical response—for both involved—can be quite acute. In short, smelling shit and describing shit in detail can elicit an intense physical response. Sensory co-presence makes no assumptions about which condition will induce a greater or lesser level of physical disgust. Rather, it delineates each as different conditions, with particular affordances, distinct from one another.

[i] In this post, I used the mundane example of project partners because these types of interaction are not typically known for their intense physicality. This therefore acts as a conservative example. If I convey my argument using it, the argument has a solid base, and can easily (and perhaps more effectively) expand to traditionally physical types of interaction (e.g. sexual activity).

Follow Jenny on Twitter @Jenny_L_Davis

Headline image via: http://www.todayifoundout.com/index.php/2010/07/humans-have-a-lot-more-than-five-senses/