At the beginning of the year, rumors were going around that the popular but relatively small citation software company Mendeley Ltd. was going to be purchased by the publishing giant Elsevier. TechCrunch ran a story and there were a few others but not much else came out of it. When I heard these “advanced talks” were taking place, I wrote an essay in which I said,

“When our accounts of reality are owned by profit-seeking organizations and those organizations control the very tools that help us exchange those accounts, we are in danger of losing something fundamental to the institution of science. Ideas should not end up behind prohibitively expensive pay walls, especially when so little of that money goes towards new scientific discovery.”

Today, Mendeley announced on their blog that their purchase by Elsevier was official. They also reassured existing users, “Mendeley is only going to get better for you.”

I’m very skeptical. Back in January, I raised the question, “what is Elsevier going to do with Mendeley that warrants uninstalling it from you computer?” and hinted that the kind of criminal charges faced by the late Aaron Schwartz could become commonplace, if not easier to prove and litigate. I also noted that Elsevier has been so malicious and aggressive in their search to control and subsequently monetize knowledge that it has inspired over thirteen thousand academics to sign a pledge saying they will not support Elsevier’s journals. They have supported SOPA, PIPA, and used to support the Research Works Act as well. Oh, and they support CISPA too. None of that has changed, and there’s still plenty to be done if Elsevier wants to gain the respect their new property once had.

A good deal of the announcement is actually devoted to calming fears about Elsevier:

“Your data will still be owned by you, we will continue to support standard and open data formats for import and export to ensure that data portability, and – as explained recently – we will invest heavily in our Open API, which will further evolve as a treasure trove of openly licensed research data.

“We were being challenged by some parts of the organization over whether we intended to undermine journal publishers (which was never the case), while other parts of the organization were building successful working relationships with us and even helped to promote Mendeley.

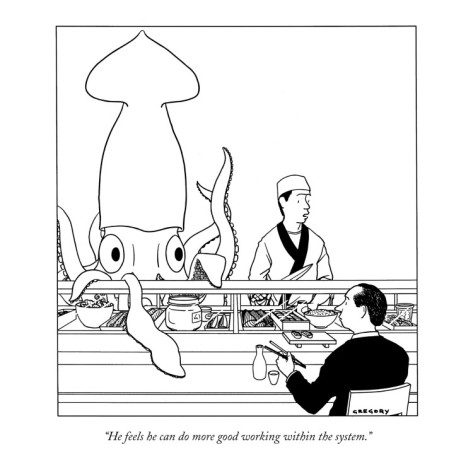

“Elsevier is a large, complex organization – to say the least! While not all of its moves or business models have been universally embraced, it is also a hugely relevant, dynamic force in global publishing and research. More importantly, we have found that the individual team members – the employees, editors, innovators, and tool developers we’ve worked with – all share our genuine desire to advance science. This is why we’re thrilled to join Elsevier and help shape its future.”

Dr. William Gunn, head of Academic Outreach for Mendeley and an accomplished biologist (according to his Mendeley profile!) was good enough to comment on my original post from January and ask, “So now that the deal is official, and both sides have said that the data will remain open and no one will get sued on account of their reading history, maybe we can revisit some of this?” He then links to Mendeley’s Q&A about the acquisition. In it, there are more reassurances that Mendeley will continue their Open API and that “there will be more and better data to work with, under the Creative Commons CC-BY license, as before.”

I have to say that I’m impressed by Elsevier’s sharp turn in this direction, and one could read this as the kind of radical change in business practices that those pledge signatories demanded. I still, however, don’t see the explicit promise that Elsevier will not sue based on reading history or what you have saved on their servers. That’s a big deal, and something I don’t want to infer from a promise of “private and secure access to your data.” If that were the only thing keeping me from using Mendeley, I would ask for something on the level of a public, written pledge from an Elsevier executive. Given that Elsevier is a “complex organization” I doubt they can make such a pledge.

Along with claims to continued open standards, the second-most repeated guarantee is that the prices will not be raised. In some respects they went down, since Mendeley is doubling storage capacities. This is a nice gesture but I have to admit it feels like the asshole rich guy just showed up to the party and bought the bar a round of drinks so that everyone will be nice to him. I’ll say thank you, but that doesn’t change who you are: a tremendous asshole.

To be clear, I’m not calling any particular person an asshole. I’m calling the company an asshole (corporate personhood has its downsides) because it hasn’t even come close to making up for the practices they have grown notorious for. I’m not a business analyst and I don’t claim to be, but I get the sense that the purchase of Mendeley is a long-term strategy meant to reposition Elsevier in a rapidly changing industry. TechCrunch (a business publication) seems to agree:

“In theory you could even now produce a ‘Klout for academics’ based on Mendeley’s data.”

Like I said. Asshole.

Ranking impact factors and selling access to important metric data looks like the future for academic publishers. Pay walls, while still holding strong, are beginning to show foundation problems. They’re the kinds of horizontal micro-fractures that aren’t necessarily signaling a near collapse, but they can’t be ignored either. A company like Elsevier loses very little from making systems on open standards because the secret sauce is really in the databases that provide the sellable analytics. From the same TechCrunch article:

“Mendeley’s tools now touch about 1.9 million researchers, pooling 65 million documents and claims to cover 97.2% to 99.5% of all research articles published. By contrast commercial databases by Thomson Reuters and Elsevier contain 49 million and 47 million unique documents, respectively.”

This is the stuff Elsevier wants and cannot duplicate. It can only acquire it through the purchase of a small company that has a very active and very social user base. Mendeley is the kind of software that sits nicely next to your Evernote account and your Dropbox. You might use all three, along with your Github and Google accounts to collaborate in Hojoki. The Mendeley acquisition is Elsevier’s first big step away from dead tree publishing and into the world of end-user web services. Its a brilliant future strategy, but it doesn’t erase the past.

What makes it possible for me to shun Elsevier’s Mendeley and still use almost all of those other services on a daily basis? Why in the world would I be totally fine with Google or Evernote buying Mendeley? Because neither of those companies have made their millions by hiding my work, or by gouging my university’s library. I am not about to applaud their decision to keep an open API when they still charge libraries hundreds of thousands of dollars just for the sake of artificial scarcity.

If Mendeley wants to hitch their horse to the Monsanto of academic publishing they can be my guest. The service will probably be amazing. But remember that the money they gave you –all the new resources you have at your disposal– were purchased with tuition money and charitable donations that should have gone to higher education. Instead, it went to Elsevier (and Thompson Reuter, and Springer and…) so that they could find new and inventive ways of hiding research so that they could continue to charge exorbitant prices. All the openwashing in the world doesn’t distract from the gigantic piles of ill-gotten money that, I suspect, the creators of Mendeley once resented.

David A Banks is trying to make #uninstallmendeley happen on twitter: @da_banks

Comments 7

Mr. Gunn — April 11, 2013

Sorry to see you go, David, and I hope that we can prove ourselves again over time.

Richard Jenkins — April 21, 2013

Excellent analysis David, thank you.

I'm a new addition to our University, and learning the joys of navigating library-funded journal searches - and I'm appalled. It's bloody awful; information is obscured, articles are stored as images within PDFs, tiny windows prescribe how many lines you can read on-line, and it goes on. It is blatantly obvious that publishing is synonymous with control in their minds, and that access is provided under extreme duress. I have no problem with my course fees paying academic salaries, even administrators wages if I grit my teeth, but I'm feeling a bit sick with the idea, as you point out, that I'm paying for this too.

Your article touched an old memory for me: a while ago, I was a technologist at the forefront of consumer computing and had gathered certain relevant skills and knowledge. These I shared freely in online forums, giving and taking in a healthy ecosystem. One day the site and it's years of accumulated knowledge and lore disappeared behind a paywall. All we had freely given and received, all our contributions, were locked away from us and we had to pay to get our own voices back. That experience, among others, has made me sceptical and less inclined to share.

I'm an advocate for FOSS and when I read that Thompson Reuter had gone after Zotero and lost, I knew which way I had to go. No regrets so far, and I will be talking to our librarians as they were equivocal when I first asked their advice. They need to take our side, I think.

ps. I heard a Mendeley founder on the Material World podcast of April 12 from the BBC, and Google led me to you.

The Place of Blogs in Academic Writing » Cyborgology — April 23, 2013

[...] peer-reviewed journals are slow, jargon ridden, and often financially pay-walled (amiright David Banks, PJ Rey!?). Blogs are fast, self-published, and usually free. That is, the content of a [...]

Elsevier has bought Mendeley! | MeNUER — July 17, 2013

[...] There is more info in this blog post [...]

Elsevier has bought Mendeley! | Conservation Science Blog — July 17, 2013

[...] There is more info in this blog post [...]

Cristina — July 26, 2013

Thanks, thanks and many many, many thanks.

I had just installed Mendeley (after many doubts because it was necessary to register!! -I'm used to free software, nothing required to install anything)... having a look... some things odd smelling ... went to the web for more information... then I found this page (and some others with similar topic and oppinions)

Fiuúuuu!... I just deleted my Mendeley account, uninstalled Mendeley Desktop and retourned to my first good idea of installing Zotero.

*Many thanks* again... (and please excuse my Spanglish :-)

(Intellectual) Property is Theft! » Cyborgology — September 11, 2013

[...] gnomes (work study students eating burritos) had retrieved my article. I download it, put it in my Zotero library and open it in iAnnotate PDF. Then I get this sad little error [...]