Recently I saw an episode of TLC’s “My Strange Addiction,” (lets not go into how exploitative this show is) and was first introduced to a man named Davecat. Davecat is a man with a synthetic partner, a growing trend where people marry anatomically correct, fully functional, mostly silicon, lifesize (sex) dolls. I call them sex dolls because they are clearly created in the image of a sexualized female ideal (small hips, large breasts, busty lips, flawless skin, long legs).

Now this is just the latest trend in a long list of what many would call “strange” new types of marriage unions. For instance, a few years back I remember a young man in Japan marrying a Nintendo DS character, and there is Zolton, the man who married a robot he built for himself, and the young man in Korea who married an anime character on a bodypillow.

Synthetic partners appear to be a growing trend, or else these relationships have simply become more visible as of late. There are several companies now specializing in these types of synthetic, lifesize dolls. There is Sinthetics brand, which appears to specialize in the pornstar variety (ie: unnatural proportions and exotic features), and there is RealDolls, made famous by the BBC Documentary “Guys and Dolls”, and the countless, extremely-creepy, celebrity sex dolls you can buy at most adult stores.

Now these trends play into what some have called “robot fetishism,” or “technosexuality.” According to the Wiki, this fetish is based on a sexual attraction to humanoid robots, or to humans dressed up like robots. We can see these sorts of anthropomorphic portrayals of humanoid robots in Svedka advertisements, in several popular anime series, and in music videos.

But what does it mean when the majority of media representations of robot fetishism are from a male perspective? Are the majority of cases actually male or is this simply a case of phallogocentrism? And why are women’s bodies so often portrayed in sexualized robot form? What does this tell us about our culture, gender, and sexuality? Finally, how has human sexuality changed as a result of these sorts of technological advancements?

Although some claim that humans react to real dolls because of our instinctual desires for abnormal, idealized, “freakish” proportions, much like an Australian jewel beetles reacts sexually to beer bottles. I personally think robot fetishism may stem from a desire for control and passivity in one’s partners. Though this is clearly not the case for ALL individuals with synthetic partners (I am sure many people are just lonely and tired of searching for a partner), it appears to clearly be the case for men like Gordon Griggs.

But there does seem to be a preponderance of males with female synthetic partners and a minority of females with male synthetic partners (Though they do sell male RealDolls, after all). What does this tell us about gender, power, and culture? I would argue that this overwhelming male bias stems from male privilege, or the belief that men are entitled to females as sexual partners. Tiring of rejection and refusal from human lovers, many men turn to synthetic ones.

Watching some of the interviews with RealDoll owners contained in the BBC documentary lends me to come to this conclusion. The men contained in the film, from socially-awkward loners to jilted lovers, all seemed to have psychological issues stemming from alienation and the inability to achieve societal expectations in coupling. Several of the men had girlfriends when they were younger, but had since become recluses unable to talk to women. Other men were simply controlling and abusive, and turned to synthetic partners because they “can’t say ‘no’” like living women can.

In conclusion, I find myself lamenting the liberatory possibilities of Haraway’s “Cyborg Manifesto”. Rather than seeing the coupling of human and machine as something which frees us from various forms of oppression (gender, race, age, infirmity, etc.), I see the phallogocentrism of robot fetishism in the mass media as myopic, exploitative, and reinforcing of existing gender oppressions. Namely, these trends reinforce the objectification of women, male sexual entitlement, and controlling behaviors in men.

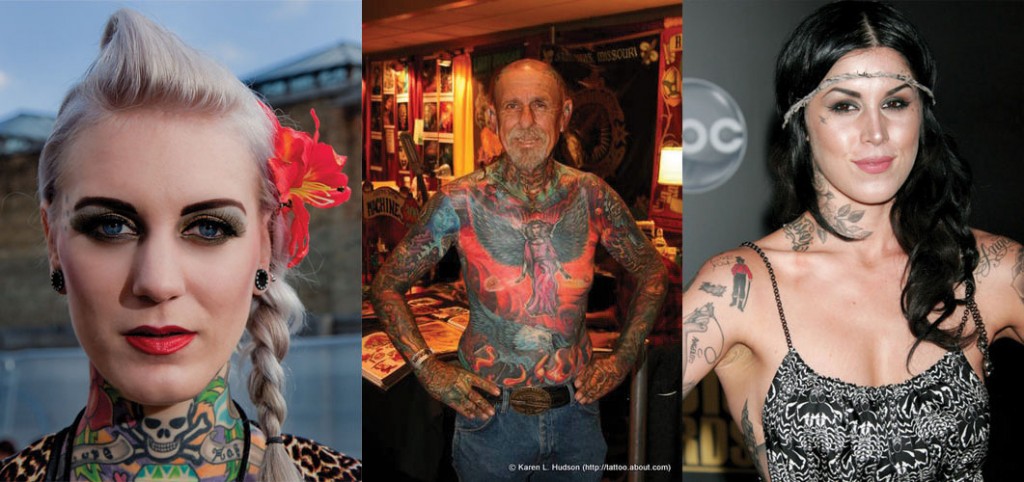

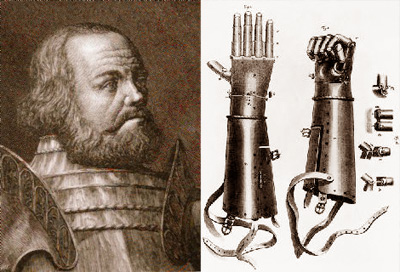

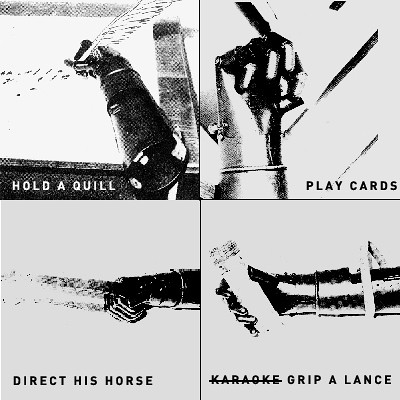

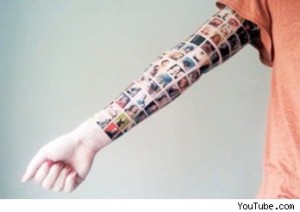

But like I have stated before, these instances of body modification are nothing new; affluent white westerners are not the first to modify their bodies in extreme ways. What is new is the use of sophisticated technology to extend and enlist the corporeal in creative ways. This Nintendo DS AR card tattoo is but one example. Perhaps in the future we will see other individuals merging body modification with other unique passions like gaming.

But like I have stated before, these instances of body modification are nothing new; affluent white westerners are not the first to modify their bodies in extreme ways. What is new is the use of sophisticated technology to extend and enlist the corporeal in creative ways. This Nintendo DS AR card tattoo is but one example. Perhaps in the future we will see other individuals merging body modification with other unique passions like gaming.