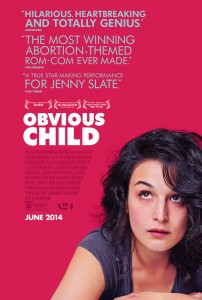

The comedy Obvious Child hit theaters last Friday, and it’s been praised as “the most honest” abortion movie Slate‘s Amanda Hess has ever seen. Honest, in that the film’s protagonist Jenny Slate decides to have an abortion and goes through with it. Her relationship does not implode, she does not suffer crippling guilt, and she survives. Her life goes on. It turns out that this kind of straightforward portrayal is a rarity in American film and television, though millions of women have abortions every year (the Guttmacher Institute pegs the number of worldwide procedures at about 42 million per year). In a recent Contraception article, a pair of sociologists report that pre-Roe v. Wade era plotlines disproportionately featured the death of women characters who even thought about abortion. After abortion’s legalization, portrayals came to suffer from a different distortion: “These movies tell us that it was wrong [before Roe] for laws to dictate what a woman ought to do with her body, but now that she has the choice, she should choose to give birth except under the most extenuating of circumstances,” Hess writes. Obvious Child rejects, well, the obvious.

The comedy Obvious Child hit theaters last Friday, and it’s been praised as “the most honest” abortion movie Slate‘s Amanda Hess has ever seen. Honest, in that the film’s protagonist Jenny Slate decides to have an abortion and goes through with it. Her relationship does not implode, she does not suffer crippling guilt, and she survives. Her life goes on. It turns out that this kind of straightforward portrayal is a rarity in American film and television, though millions of women have abortions every year (the Guttmacher Institute pegs the number of worldwide procedures at about 42 million per year). In a recent Contraception article, a pair of sociologists report that pre-Roe v. Wade era plotlines disproportionately featured the death of women characters who even thought about abortion. After abortion’s legalization, portrayals came to suffer from a different distortion: “These movies tell us that it was wrong [before Roe] for laws to dictate what a woman ought to do with her body, but now that she has the choice, she should choose to give birth except under the most extenuating of circumstances,” Hess writes. Obvious Child rejects, well, the obvious.

Watch the trailer for the film here.