In December, thousands watched tall, thin models parade bedazzled bras, panties, and angel wings down the runway at the Victoria’s Secret fashion show. In the U.S., however, these “standard size” models aren’t representative of either the female population (an average size 10-14) or of the entirety of the modeling population.

In December, thousands watched tall, thin models parade bedazzled bras, panties, and angel wings down the runway at the Victoria’s Secret fashion show. In the U.S., however, these “standard size” models aren’t representative of either the female population (an average size 10-14) or of the entirety of the modeling population.

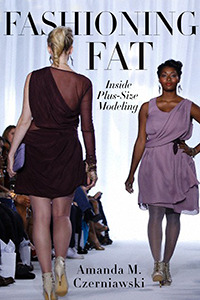

Sociologist Amanda Czerniawski, who worked as a plus-size model in researching her book Fat: Inside Plus-Size Modeling, was featured in a Pacific Standard article about the opportunities and limitations for plus-size models in the fashion industry. She explained that featuring plus-size models can be considered an “act of resistance” against the fashion industry’s standard ideals. Still, while plus-size models contribute to a more inclusive idea of beauty, Czerniawski said the status quo is hard to change:

Though plus-sized models want to change notions of beauty and glamour, she argues, the industry restricts their efforts and their effectiveness. Plus-sized models are not really all that free; though they do not have to be a size zero, their bodies are still regulated and policed.

The article goes on to explain how some plus-size models find themselves labeled too small, too big, or not the right type for a given job. Further, though plus-size models continue to gain visibility in the fashion industry, they still have fewer opportunities than “straight” (that is, willowy) models.

In the end, all modeling is about capitalism:

Many of the indignities that Czerniawski details—lack of benefits, arbitrary management decisions, exploitative contracts—are typical of many (most?) labor relationships under capitalism.

This means including a wider range of sizes among models is unlikely to change the regulation of their bodies; it’ll just mean more women in a glamorous and restrictive sector of sales.