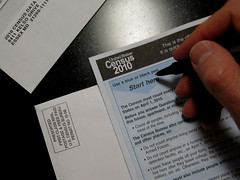

With political representation and federal funding at stake, Midwestern states are showing the highest Census response rates so far. According to the New York Times:

With Thursday dubbed Census Day — the day the questionnaires are meant to capture as a snapshot — South Dakota, Wisconsin, Nebraska, North Dakota and Iowa are ranked the top five states by federal officials, because they have the highest participation rates in the census so far. People can send in the forms until mid-April, but the Midwest’s cooperativeness might rightly worry other regions.

After all, the census guides the federal government on decisions with lasting impact — like how many representatives states will have in Congress and how much federal money they win for their roads.

But the high rates of participation in these rural states may have less to do with vying for power and resources and more to do with social norms and sensibilities.

Census officials said lots of social factors seemed to correlate to a community’s responsiveness (or silence) to the census mailings. Places where people stay put, for instance, often answer. In this town, most people said they had grown up here.

But some North Dakotans, where the state capital, Bismarck, had the nation’s fourth-highest response rate among larger cities as of Wednesday night, suggested a simpler answer. Perhaps it was the way of thinking around here — some combination, they said, of being practical, orderly, undistracted and mostly accepting of the rules, whatever they are. “We have a high degree of trust in our elected officials,” said Curt Stofferahn, a rural sociologist at the University of North Dakota, “and that carries over to times like these.”

The towns and cities the census described this week as having 100 percent participation rates are mostly tiny. How hard, some wondered, is it to get 50 responses from 50 people? And in Wolford, which officially has a 100 percent rate, plenty of people — perhaps more than 20 — are not included in that statistic because they hold post office boxes and have yet to receive forms.

By all appearances, these norms are being passed along to the next generation of rural residents.

At Wolford Public School, where 46 children from around the area attend kindergarten through 12th grade (the ninth grade is empty and only one child is in fourth grade), census leaflets, posters and stickers have been handed out in Wanda Follman’s class of 11 children.

Asked on Wednesday if their families had returned census forms yet, nearly all 11 shot their hands in the air. The children excitedly recited some of the questions from memory.

“I filled it out with my mom’s help,” said Kyle Yoder, the 8-year-old, who wore glasses and a serious face. “It was kind of easy.”

God is really popular in the U.S., reports the

God is really popular in the U.S., reports the