It has been a tough year for Chicago. A recent surge in gang conflicts has increased crime—so much so that Chicago saw its 400th murder of 2012 by the beginning of October. In a New York Times op-ed, Sudhir Venkatesh, Columbia sociologist and author of Gang Leader for a Day, describes ways in which the efforts to control guns in Chicago are insufficient. Venkatesh explains:

Homicides are up about 25 percent over last year. Chicago has surpassed New York and Los Angeles as a hub of gun-related violence, most of it involving young people. Since 2001, it has recorded more than 5,000 gun-related deaths, compared with the 2,000 American military deaths in the war in Afghanistan.

Venkatesh sees several ways to improve outcomes for Chicagoans. First, he identifies a police focus on finding “gun-runners,” who buy from licensed dealers and resell to others, when nearly half of gun purchases actually come from a secondary market comprised of gangs, gun brokers, or informal traders such as family or friends. He suggests more amnesty programs like gun buyback programs could help here. Next, Venkatesh fingers a lack of support for mediation programs like Boston’s CeaseFire. These programs help open up conversations between gang members and police officers, and have been shown to lead to sharp declines in gang violence.

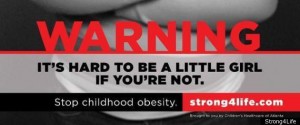

Finally, Venkatesh turns to a back to how guns get from person to person. A surprising amount of firearms, he writes, are passed between friends and family, and he believes a sensible, “clever” media campaign must be launched to discourage gun-lending.

These may seem like small steps, but they could have very important effects. As Venkatesh puts it, “Good gun policy is good social policy.” To underscore the point, he turns to his Freakonomics colleague, Steven J. Levitt, who has estimated “each homicide is associated with out-migration of 70 city residents. The total social costs of gun violence in Chicago have been estimated at about $2.5 billon—$2,500 per household—a year.”