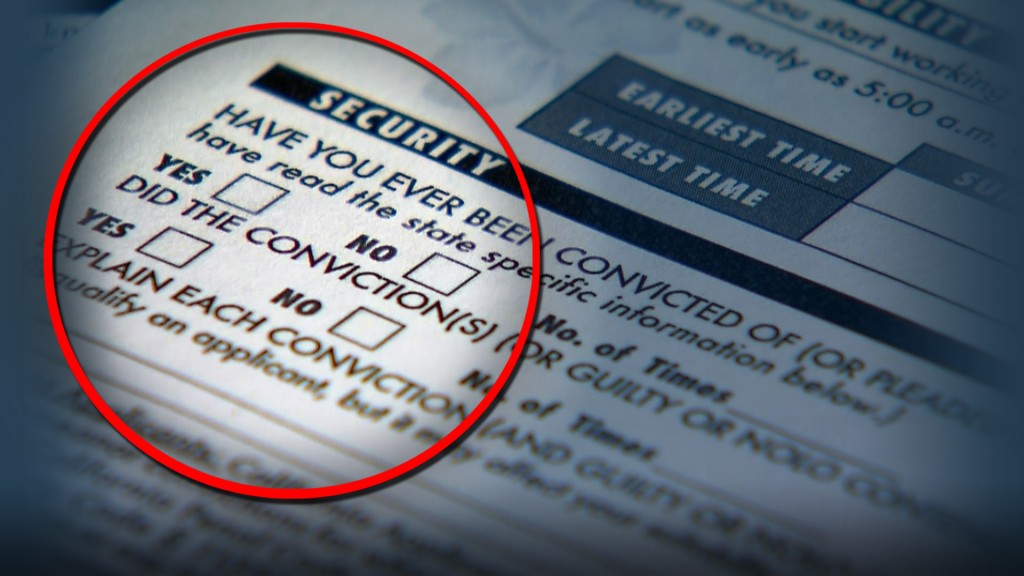

As noted by Harvard sociologist Devah Pager, experimental evidence indicates that the presence of a criminal record reduces one’s application callback likelihood by 50% for whites and 64% for African Americans. To potentially mitigate this employment discrimination, 23 states have adopted “ban the box” policies—the removal of the criminal history question on first-round job applications. However, a pesky question remains in the minds of many employers: do felons make good employees?

National Public Radio’s Planet Money Podcast, hosted by Keith Romer, asked Pager how felons fare if they gain employment. To get at the answer, Pager has been studying felon enlistment in the military (5,000 enlistees between 2002-2009 had felony records). She finds that those with felony records are no more likely to get kicked out before the end of their term than their clean-record counterparts. In fact, those with felony records are not only promoted faster, they are also promoted to higher ranks. Pager contends that “employers are probably missing a lot of talent when they exclude people with criminal records” (notably, with few exceptions, the military is not currently accepting felons). Because it is often so hard for ex-cons to get a job, they seem to work particularly hard to keep that job. Overall, Pager’s evidence appears to show that steps to “ban the box” will bring qualified applicants rather than unwanted mischief to employers.

With the baby boomer generation hitting retirement ages, it’s important to consider how retirement affects this enormous cohort and their families. One unique aspect of today’s retirement is the occasional retirement overlap: both parents and children are retired at the same time. In an interview with The New York Times, Phyllis Moen of the University of Minnesota says,

This is still historically unprecedented, where you have older people and their still-older parents. Families are having to figure out those intergenerational relationships.

This may be a situation unique to the current time period, though. For the trend to continue, the younger generation must retire while their parents are still alive. Since expected and actual retirement ages have been rising for more than a decade, future generations may not be able to afford to retire at all, let alone alongside their parents. Then again, “by the time their children retire, we may have even more medical advances to help us live even longer,” says Professor Moen.

One potential downside of dual-generation retirements is that they can add retirement stress in the form of caregiving for older family members. As Moen states, “The pressures are less intense while the younger generation is still employed,” because “work can offer an escape from the stress of caregiving and the stress of that family relationship.”

From OJ Simpson to Casey Anthony, America has no shortage of highly anticipated and hotly discussed trials. At the moment, Boston is a hive of judicial, legal, and media activity surrounding the trials of two infamous, if unrelated defendants: Boston Marathon bombing suspect Dzhokhar Tsarnaev and New England Patriots tight-end and homicide suspect Aaron Hernandez. An article from ABCNews by Denise Lavoe uses sociology to explain why some trials can gain so much attention and how that affects the ideal of trial by a jury of peers. In each of the Boston cases, jury pools reached well over 1,100 people until a group of potential jurors who hadn’t already reached a conclusion about the case could be found.

Quoted in the article, Northeastern University sociologist Jack Levin explains that each trial attracts interest and media attention in a specific way. People are interested in the Tsarnaev case because of “a widespread feeling that people have that they are vulnerable.” The fear of terrorism drives public interest rather than the fame of the defendant. The Hernandez case is different, as Levin explains, because the trial of a popular sports figure attracts its own kind of attention. Society, he says, places “tremendous value on athletes, and when one of them commits a serious crime like homicide, it shocks the public.” The trial of a disgraced, once-popular player draws public attention partially because the narrative seems to run so counter to prevailing perceptions of sport and athletes, as well as the gloss of fame. Tsarnaev is felt keenly as a physical threat to everyone, while Hernandez represents a more abstract threat to assumptions and values. Both cases will likely remain front-page news well into the future, but different social processes lay beneath their infamy.

Bill Cosby is a household name, once associated with a long and illustrious career, now with an infamous string of sexual assault allegations dating as far back as 1965. After new rape charges arose in late 2014 and became the subject of pop-culture discussion, TVLand dropped The Cosby Show from its rerun schedule and Netflix postponed a Cosby comedy special. A sitcom he had in development was canned. Notably, Cosby had weathered such accusations for decades without losing the support of networks and business partners. This time has been different.

University of Texas-Austin sociology professor Ari Adut lends his thoughts in a New York Times article. When public knowledge about a scandal is limited rather than widespread, entertainment businesses are less likely to take action. Once an allegation leveled against a public figure and becomes common knowledge, though, businesses are compelled to respond: “[w]hen everyone knows that everyone else knows about the claim (and so on), society can judge people and groups that do not act on that knowledge.” So, though rape and assault accusations had followed Cosby for nearly a half-century, the latest set of allegations have been hotly discussed in the media, and groups like Netflix moved to distance themselves from the performer so as to avoid public perceptions of Inaction.

This sociological explanation for how businesses assess public opinion regarding scandals and act accordingly helps us understand many other occurrences in the entertainment industry. For example, after actor Charlie Sheen had a run-in with the NYPD regarding drugs in 2010, CBS soon dropped the star from Two and a Half Men, despite the fact that Sheen had notoriously faced drug issues before. Once Sheen’s 2010 crime became public knowledge, the axe fell swiftly. For the famous, what the public doesn’t know—or mobilize around—needn’t be a worry. When it hits the front pages, though, anything from “dirty laundry” to felony assault is likely to tarnish a even a star’s brand image (and paychecks).

Although some research emphasizes the negative impacts of social media on well-being, a recent Smithsonian article highlights a specific benefit: social media platforms allow individuals to connect across thousands of miles. Further, despite anecdotal evidence, social media usage does not actually result in higher stress for users.

Although some research emphasizes the negative impacts of social media on well-being, a recent Smithsonian article highlights a specific benefit: social media platforms allow individuals to connect across thousands of miles. Further, despite anecdotal evidence, social media usage does not actually result in higher stress for users.

Dhiraj Murthy, sociologist and author of the book Twitter, told the Smithsonian Magazine about how social media lets people keep up with friends and family members, whether it’s communication about big events such as births or weddings, or every day things like food or funny cat videos. By fostering a sense of connectedness, Murthy says, this communication can reduce stress and increase happiness.

Still, Murthy warns, “Increased social awareness can of course be double edged.” Connectedness can mean feelings of stress, sadness, or anger when the interactions relate to death, job loss and other heavy topics. This means it’s the content viewed on social media, not social media itself that affects stress levels.

While the relationship between social media and stress is complex, many such studies focused on heavy users, Murthy says. In general, the common perception of most social media users as gadget-addicted stress cases doesn’t hold up to scrutiny.

Busy schedules coupled with near constant access to technology contribute to people becoming more social via social media. While sharing a cup of coffee takes coordination and time, a quick scroll through an album or a post about a promotion allows users to participate in communal behaviors that benefit mental health. If the trick is focusing on the good content without ignoring the bad, it seems our online interactions are an awful lot like the in-person ones.

Jason Deitch, a UC-Berkeley PhD in sociology, has long been fascinated with the cultural effects of war. A veteran, Deitch has served as an advisor and activist in many capacities, but his newest project, produced in his capacity as an advisor to the California State Library, is gaining national recognition. Along with Chris Brown of the Contra Costa County Library system, the StoryCorps Military Voices Initiative, filmmaker Rebecca Murga, and photographer Johann Wolf, Deitch set out to interview as many of California’s estimated two million veterans as he could.

Jason Deitch, a UC-Berkeley PhD in sociology, has long been fascinated with the cultural effects of war. A veteran, Deitch has served as an advisor and activist in many capacities, but his newest project, produced in his capacity as an advisor to the California State Library, is gaining national recognition. Along with Chris Brown of the Contra Costa County Library system, the StoryCorps Military Voices Initiative, filmmaker Rebecca Murga, and photographer Johann Wolf, Deitch set out to interview as many of California’s estimated two million veterans as he could.

Well, at least the ones with tattoos. As Deitch told PBS’s NewsHour:

These tattoos are an expression from a community that doesn’t openly discuss or express emotion…. We understood these tattoos to be uniquely valuable, as veterans largely return home to a community that doesn’t know their story and how war changed them… That can be an incredibly isolating experience…

He went on to say that it was tough recruiting vets willing to show off their ink and talk about their experiences on the frontlines, but he hoped the resulting exhibit, “War Ink,” would help “bring veterans out of isolation by helping people back home understand them.”

Participants described the process of being photographed and recounting their stories as a way to educate others about a struggle that doesn’t end with their tour of duty.

When Julia Pierson’s name first appeared in national headlines last year, it must have sounded like a perfect solution. President Obama appointed Pierson as the nation’s first female Director of the Secret Service following the aftermath of an embarrassing scandal in which several agents hired prostitutes on a presidential trip to Columbia. Many saw Pierson as uniquely positioned to purge the organization of its hyper-masculine culture and revive its good name.

After an intruder succeeded in running across the lawn and into the East Room of the White House, however, a firestorm of criticism prompted Pierson’s resignation. Writing in the New Republic, Bryce Covert suggests that the very gendered conditions of Pierson’s hire preconfigured her administration’s failure from the start. Such is the unfortunate case, he argues, for a large number of women in leadership roles:

As with Pierson, women are often put in these positions because rough patches make people think they need to shake things up and try something new—like putting a woman in charge. When it’s smooth sailing, on the other hand, men get to maintain control of the steering wheel. Women are also thought to have qualities associated with cleaning up messes.

You’re familiar with that unseen barrier to power called the “glass ceiling”? Covert cites research by psychologists Michelle Ryan and Alex Haslam to show that female leaders often reach top jobs that come with an inordinately high risk of failure. Social scientists call this precarious position the “glass cliff”.

Covert builds his case on a wealth of research exploring the risks that await women at the top of the corporate world:

Multiple studies have found that women are most likely to be given a chance at top roles in the corporate world when things are already bad. One found that before a woman took over as CEO of a Fortune 500 company between 1996 and 2010, its previous performance was significantly negative. Another found that FTSE 100 companies who appointed women to their boards were more likely to have had five months of consistently bad performance compared to those who picked men. Another found that companies were most likely to choose women for their boards after a loss that signaled the company was underperforming. Even in a lab, students and business leaders are more likely to pick a woman to lead a hypothetical organization when performance is on the decline.

Looking for more on the barriers facing women in positions of power? Our own Anne Kaduk shows “There’s Research on That!”

During election season, we are treated to story after story about how candidates have made themselves out of nothing. Wisconsin Governer Scott Walker, locked in a tight reelection battle with Mary Burke, his Democratic opponent, has made a career of turning talk about his lack of a college degree into a story about upward mobility rather than academic insufficiency. Much of Joe Biden’s appeal as both a Senator and a Vice President comes from his salt of the earth appeal as the son of father who faced financial ruin, lived with his grandparents, and, through hard work and dedication, made something of his life. Candidates on both sides of the aisle tap into the discourse of upward mobility to demonstrate that they understand the struggles of the people they hope will elect them.

When candidates talk about how they have pulled themselves up by their bootstraps on the campaign trail, they’re doing more than lauding their own humble pasts to gain voters’ trust. They’re also tapping into a social narrative that’s been used throughout American history to determine what counts as economic success and who it’s available to. At the same time as it aligns candidates with desired swaths of the electorate, especially middle-class whites who turn out in numbers, it also implies a subtle distance between candidates and social problems. All of us can do this, if only we try hard enough, goes the implied reasoning, and if you can’t do it, that’s on you. Who can’t do it? As usual in American society, that would be the out-groups: non-whites, immigrants, LGBT people, and the disabled. Advocates of the bootstraps school of social mobility like to counter this critique by linking economic success to cultural values. They point out that immigrant Jews have largely succeeded economically, while African Americans still struggle, and attribute this to a set of American cultural values that Jews share, but blacks don’t.

In an excellent longform Slate article on this topic, John Swansburg cites sociologist Stephen Steinberg’s 1981 book The Ethnic Myth, a critique of what Steinberg calls the “Horatio Alger Theory of Ethnic Success,” or the belief that all social outgroups start with the same set of disadvantages. Most early 20th century Jewish immigrants, Steinberg argues, came from urbanized, industrial European cities, where they gathered “years of industrial experience and concrete occupational skills that would serve them well in America’s expanding industrial economy.” Most American blacks, on the other hand, learned farming and field work—skills that benefited them little as they moved to the industrial North after Reconstruction.

When Scott Walker, Joe Biden, or any other candidate for office talks about his or her humble past, he or she is making a subtle implication that the problems of disadvantaged groups in America are mostly cultural, rather than economic or structural. I know how to work hard and I know you do too, so elect me and I’ll make sure that our kind of work is rewarded. And those others, whose work is never rewarded? Well, they’re just not working hard enough.

For more on how candidates construct narratives to court voters, read (or listen to!) Jeffrey Alexander’s “Heroes, Presidents, and Politics,” now in podcast form.

Damn kids today. Do we have to do everything for them? I, for one, do not have the time to egg cars and throw basement parties. But if Joel Best and Kathleen Bogle are right, teens are less deviant than ever, no matter how prurient the headlines.

Damn kids today. Do we have to do everything for them? I, for one, do not have the time to egg cars and throw basement parties. But if Joel Best and Kathleen Bogle are right, teens are less deviant than ever, no matter how prurient the headlines.

Bogle explains to Salon,

in previous generations they were worried about going steady, they were worried about lipstick, they were worried about miniskirts, they were worried about rock music. It’s not new for parents to worry about kids or that their pop culture interests or their access to the opposite sex is going to lead to trouble. We’ve been worried about that for a long time…

But rainbow parties! But red bracelets! But twerking!

The authors of the new book Kids Gone Wild: From Rainbow Parties to Sexting, Understanding the Hype Over Teen Sex tell Salon about their conscious choices to feature sensational media stories that fuel parents’ fears, schools’ regulations, and kids’ secret gossipy delight, to the near-disappointment of the article’s author:

When it comes to concerns about kids these days… the authors found scant evidence… The main takeaway of the book, which is more academic report than popular nonfiction read, is that these tales [of rainbow parties and out of control sexting] were not driven by fact but rather by a media willing to exploit parents’ worst fears for ratings and readership.

As the article continues, tracing the origins of salacious teen myths, it’s pointed out that Bogle and Best could have “easily chosen the pregnancy pact story or some of the other stories that have gone around.” Bogle says, almost ruefully, when she tells friends she’s studying adolescent behavior and finding “kids actually have not gone wild,” they nod and pause before saying, “‘But kids today are really a problem…,’ It’s always the idea that kids today are worse than ever before.”

Criminy. Guess I’ve gotta get to Costco to stock up on toilet paper and wine coolers. Apparently the kids just refuse to corrupt themselves.

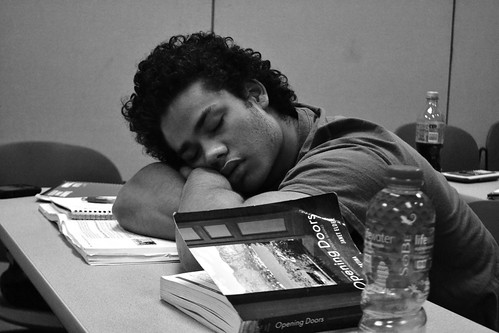

College students are tired of sleeping, according to a BBC interview with Catherine M. Coveney. She’s a British sociologist who recently explored the sleeping practices and subjective sleep experiences of two notoriously sleep-deprived groups: shift workers and college students. After conducting 25 semi-structured interviews with individuals dispossessed of rest, she concludes that our social context impacts how we understand the meaning of sleep and how we manage our sleeping schedules as a result.

The hospital-based doctors, nurses, police officers, call center employees, and other shift workers Coveney interviewed describe actively managing their sleep schedules around work patterns, finding childcare, and spending time with their partner. It is something that is constantly at the back of their mind. To illustrate why they view “broken sleep” as part and parcel of the job, Coveney explains how sleeplessness is built-in to the work structure:

There are some occupations where nothing is sanctioned…. The two nurses that I spoke to, they had to work waking nights. So even on their break, they weren’t allowed to go to sleep during the night. That’s not to say it didn’t occasionally happen, but that it was not a sanctioned practice. That was something that was seen as going against the rules of their profession.

On the surface, the sleep patterns of the college students look identical to the shift workers: “They did describe a kind of similar pattern; they did describe taking naps during the day, having a shorter sleep at night, having a two hour nap the next day.” Yet because they see sleep as an “expendable luxury,” they don’t view their own erratic sleep as “broken.” According to Coveney, for the college students,

…it was more flexible, it was more their choice, so in a sense they were customizing their sleep patterns to fit around their social activities…. I suppose it was seen as disposable in a sense, they could cut back on sleep if they chose to, they could indulge in sleep if they chose to.

Although both groups thought of sleep in functional terms—the necessary amount determined by what was needed to get them through what they had to do the next day—Coveney reports, “None of the students I spoke to said they would prioritize a night in bed because they thought they hadn’t had enough sleep. If there was something else they wanted to do, they‘d do that. And they’d catch up later, they’d sleep longer the next day, they’d take a nap…. Some of them did go as far as to say if they could get rid of their need for sleep, it would give them much more time to do other things.” Even the value of sleep depends on supply and demand.

To learn who else is getting more sleep than you are, check out these TSP classics on the gender sleep gap and on segmented sleep.