A debate about just how gender progressive Millennials are has been created by a CCF online symposium. In it, Joanna Pepin and David Cotter report that attitudes toward gender equality are not always consistent: There are different trends in attitudes toward gender equality for the public world of work and the private world of the family. They suggest that while Millennials’ attitudes toward women’s rights in the world of work remain feminist, they are less likely to support equality at home than did the last generation. They use nationally representative data from surveys of high school seniors to support their argument.

We use different data and replicate their argument about the complexity of gender attitudes. But we find no evidence that Millennials are moving backward on their commitment to gender equality. Our analysis is based on attitudinal survey questions on gender questions in the General Social Survey pooled from 1977 to 2014. We then draw on just released 2016 data from the same survey to illustrate the results about Millennials today. In the analysis using data from 1977 to 2014, we measure attitudes toward women in the public sphere with a question that asked whether men are better suited emotionally for politics than are women. We measure attitudes towards women’s role in families with three questions: Is it better if the man is the achiever outside the home and the woman takes care of the home and family; whether a working mother can establish just as warm and secure a relationship with her children as a mother who does not work; and whether a preschool child is likely to suffer if his or her mother works.

We use a different method than did Pepin and Cotter. We let social groups emerge empirically from the data, without pre-determining who would show up in each group (statisticians call this latent class analysis). We label the groups based on their answers to these questions about gender equality and then describe what kinds of people hold what attitudes. We traced the kinds of people in each group over decades and can describe them by race, educational status and sex. Our analysis confirms that there are indeed distinct differences between gender attitudes toward equality in the public sphere and equality within families. But we show this is not a new split. It’s one that is decades old, and our results suggest the split emerged by the 1990s.

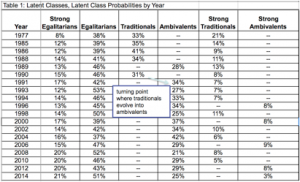

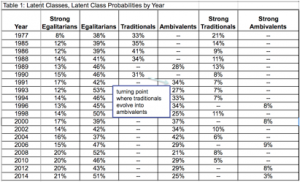

Three major groups were formed by how people’s answers clustered (see Table 1). There were egalitarians who approved of equality in the workplace and the home. There were traditionalists who rejected equality in both the workplace and the family. And then there were the ambivalents who approved of gender equality in the workplace but not in the family. (In our actual analyses each of these groups was furthered divided into those with strong beliefs and those with moderate beliefs and the table below is presented to show that distinction.)

Where have all the Traditionals gone? The big historical story is that there are no more traditionalists. From 1977 to about 1990, about a third of Americans were traditionalists and did not believe women and men should have the same rights and opportunities at work or at home. In that era, there were almost no ambivalents. Everyone was either traditional or egalitarian. But what changed after 1990 was that the traditionalists became ambivalents. That is, by the early 1990s those who used to reject equality totally had accepted women’s right to equality at work but still resisted equality in the family. Americans who have a carte-blanche objection to gender equality in both the workplace and the home have become almost extinct. Score one big win for the feminist revolution. But the victory is partial because those traditionals have not become egalitarians, they have become ambivalents, and this is a reminder that feminist have much work to do before everyone believes in gender equality within the family.

Table 1. Are Millennials Rejecting the Gender Revolution?

(Authors’ Analysis from General Social Survey data, 1977-2014.)

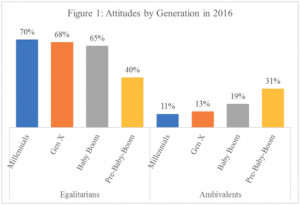

Our next step was to analyze what demographic characteristics were more likely to be associated with being egalitarians vs. ambivalent for each year in the data from 1991 to 2014. We do not include traditionals here because they are almost extinct. To do this, we conducted a multinomial logit latent class regression (the analysis is available upon request). Millennials are as likely to be egalitarians as the generation immediately before them (often called Gen X). We find no retreat from equality but also no statistically significant change toward feminist attitudes among Millennials. Rather, attitudes have leveled off. The biggest generational shifts remain between Baby Boomers and their parent’s generation.

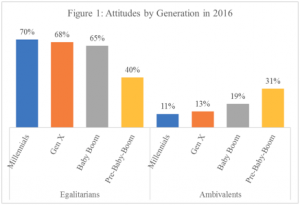

While Americans who believe in gender equality in the workforce but not at home still exist, they are most likely to be pre-Baby-boomer men, without a college education. In the General Social Survey data we find no evidence that Millennials have ambivalence to gender equality, nor that they are more likely to endorse traditional family forms than those in the past. We illustrate this argument with a descriptive summary of the data from the year 2016 (in Figure 1).

Conclusion. The traditionalist who believes women do not belong in the public sphere is now a dinosaur. Almost no one in American society believes women do not deserve equality in the public sphere. But those traditionals did not become egalitarians, rather they held on to traditional beliefs about women’s place in the family.

Conclusion. The traditionalist who believes women do not belong in the public sphere is now a dinosaur. Almost no one in American society believes women do not deserve equality in the public sphere. But those traditionals did not become egalitarians, rather they held on to traditional beliefs about women’s place in the family.

This is not a new story. The big swing toward more egalitarian attitudes toward women in the family can be traced to the era of the Second Wave of feminism. Our evidence shows that while Baby Boomers were the pioneering feminist birth cohort who experienced a generation gap with their own parents, those after them have inherited egalitarian attitudes but have not pushed the envelope, at least not as represented in this national dataset. Still, there is no evidence in these data of a backward slide among Millennials. It is the oldest generation, the parents of Baby Boomers, who remain the most likely to be ambivalent about gender change. These national survey data suggest that Millennials may not be pushing boundaries on gender attitudes but they do continue the slow march trend toward egalitarianism that Baby Boomers began.

Originally posted 4/18/2017

Barbara J. Risman is Professor of Sociology at the University of Illinois at Chicago and President of the Board of the Council on Contemporary Families. Ray Sin is a behavioral science researcher at Morningstar Inc. and a doctoral candidate at the University of Illinois at Chicago. William Scarborough is a doctoral candidate at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

The Council on Contemporary Families Gender and Millennials Online Symposium presents research on how Millennial men and women are changing—and how they are not changing. Countering the recent trend of ignoring inconvenient facts, this symposium makes it clear that attitudes about gender equality are more complex than either supporters or opponents of feminism often admit. Here’s a quick review of the brief reports.

The Council on Contemporary Families Gender and Millennials Online Symposium presents research on how Millennial men and women are changing—and how they are not changing. Countering the recent trend of ignoring inconvenient facts, this symposium makes it clear that attitudes about gender equality are more complex than either supporters or opponents of feminism often admit. Here’s a quick review of the brief reports.