Evidence from Long-term Time-use Trends

In a period of “long-term stuttering social change,” the authors argue that men are making progress toward reducing structures of gender inequality.

As women entered the paid labor force in the 1970s and 1980s, time use studies found that wives began spending less time in housework, while husbands began increasing their time (Robinson 1979). But these changes certainly did not lead to parity, and in the late 1990s and early 2000s, progress in gender equality at home and in the public sphere appeared to slow – or even stall.

We argue, however, that like most momentous historical trends, we shouldn’t expect progress towards gender equality to happen in an uninterrupted way. Just as we still see cold snaps within a process of longer-term climatic warming, the progress of gender equality should be seen as a long-term, uneven process, rather than as a single, all-at-once revolution.When we take a broader and longer view of key trends in the gender division of labor, it is clear that despite periodic setbacks or slow-downs, there has been continuing convergence in the roles and attitudes of men and women. For this paper we studied such trends in 14 developed countries over a 50 year period, using a multinational archive of time-use diary data.

Long term changes in housework and care.

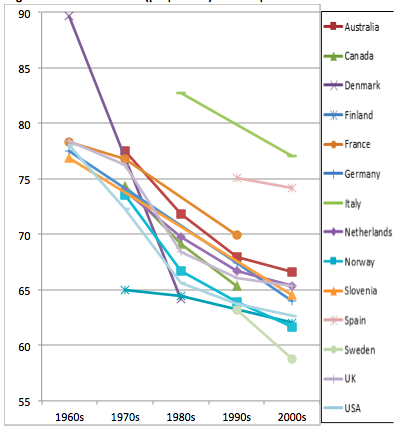

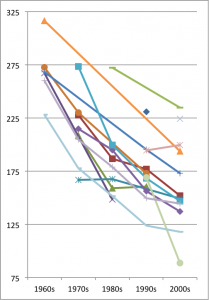

Researchers often look at the division of core housework as a measure of gender power in households. Across the 14 countries surveyed the time women spent in cleaning, cooking and laundry showed a striking downward trend over this extended period, with a less impressive, but nonetheless largely consistent, increase for men (shown in Figures 1a and 1b respectively). These graphs show that women’s hours of core housework stood at well over four hours a day (260 minutes and more) in most of those countries for which we have records from the 1960s – the USA being the exception at just under four hours (228 minutes). A rapid decline is then evident over subsequent decades to a level of below 2 ½ hours a day (150 minutes) in most countries by the first decade of the 21st Century. The exceptions for the later period are the southern and central European countries of Italy, Spain, Austria, Slovenia and Germany, where women’s core housework hours remained at levels of at least 175 minutes a day or more.

Men’s hours of core housework were more variable over time, but in all countries for which we have records men did less than an hour of core housework in the 1960s (with the strange exception of Slovenia, at 65 minutes!). In contrast, by the 2000s, in almost all countries men did between an hour (the USA) and an hour-and-a-half (Norway) of core housework per day. Again, though, men in the southern European countries (Italy and Spain) did less.

These graphs also show 1) that there is still a substantial difference in the time that women and men spend on core housework (note that the vertical scales of the two graphs barely overlap), and 2) that from the 1990s onwards there has been some leveling off or decline in men’s contributions in certain countries. In particular, a decline is observable both in those countries where men already contribute a lot of time (Norway, Finland) and, more worryingly from a gender equality perspective, in some Anglophone countries where men’s contributions are not nearly so high (the USA, Australia). However, if we take the longer view, looking at the overall picture, there is little compelling evidence for a “stall” in the cross-national long-term trend towards greater equality in housework.When we add other kinds of housework and care to the picture, we get a more complex picture still. Women have substantially decreased their time in housework. Men have increased their time in housework in comparison to the most of the past, but since the 1990s that increase has slowed or in some cases declined. However, men and women alike have increased their time in two other kinds of unpaid family activities.

One trend is a growth in the time spent in shopping, reflecting both an increase in the volume of consumption, as a result of the rising tide of affluence throughout the second half of the 20th century, and the replacement of local retail establishments by large self-service supermarkets, requiring extra travel time in private cars. For example, in the USA since the 1960s the average time men spend in shopping and domestic travel per day has risen from fewer than 50 to more 60 minutes. For women the increase was from 60 to 80 minutes per day.

The other is a growth in the time parents spend in childcare. This growth has been particularly striking for fathers: For example, the time that US fathers spent caring for children over the period from the 1960s to the first decade of the 21st century almost doubled for high-school-educated fathers and more than tripled for college-educated fathers (Sullivan, 2010).

When we combine all three activities (shopping, housework, and childcare) in our study, we see a clear-cut increase over the past half-century — in every single country included in the survey – in men’s daily time spent in unpaid family work and care. Women continue to shoulder a disproportionate load of the unpaid work, in part because they spend fewer hours in paid work than men. But even taking this into account, there has nevertheless been an obvious, cross-national increase in men’s contributions. This increase, together with the overall decrease in women’s core housework shown in Figure 1a, helps account for the steady and systematic decline in women’s relative share of the overall burden of unpaid work across time and across countries — shown in Figure 2. This graph shows that women’s share of unpaid work and care fell from levels between 75 to 80 percent in the 1960s to levels between 59 and (Sweden) and 67 percent (Australia) by the 2000s. (The exceptions are Italy and Spain, where women’s share of the overall unpaid work and care is still relatively higher, although it has declined over time to around the 75 percent level).

In terms of broad distinctions in trends between countries in women’s share of the unpaid work and care burden, the North American countries (the USA and Canada) have performed slightly better than both the UK and continental European states such as the Netherlands, Germany and Slovenia, and much better than the southern European countries (Spain and Italy). Scandinavian countries (Denmark, Sweden, Norway and Finland) have shown the most consistent trends in the direction of gender equity. In the first decade of the 21st century men from the Scandinavian countries were contributing between 38 percent (Finland, Norway) and more than 40 percent (Sweden) of all unpaid domestic work and care, compared to between 35 percent in the UK and Netherlands and 37 percent in the USA. In Spain, men still did less than 30 percent — and in Italy, just 25 percent.

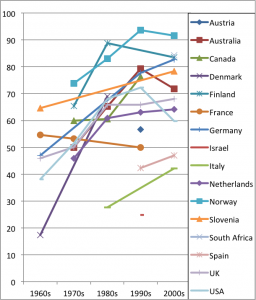

Of course, on average men spend more time in paid work than women. When we turn our attention from the gender division of domestic labor to the overall gender division of labor – the total amount of all paid work, housework, and family care that men and women do – the result is quite striking. Women’s share of all work clusters closely around the 50 percent mark, representing equal work-loads (Figure 3). Throughout the period shown on the graph, women in Finland, France, Slovenia, and, most notably, Italy did slightly less than half of total paid and unpaid work, while in the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, and Australia, they did marginally more work than men.

Conclusions and policy implications.

In any long-term process of social change we might expect to see some levelling, even reversals, in the general trend. But the combination of a historical trend in the direction of both public and domestic gender equality and the general increase in attitudinal support for greater equality seriously challenges the idea that progress towards gender equality has stalled. It suggests, rather, that we are still in the midst of a long term process of stuttering social change. In contrast to the idea of revolution, we argue for a different metaphor; a slow dripping of change, perhaps with consequences that are barely noticeable from year to year, but that in the end is persistent enough to lead to the dissolution of existing structures.

These changes are important. But we should not expect too much from them in a short period of time, and neither should we be complacent about the future. This is because despite widespread attitudinal support for ‘fairness’ in the gender division of labor, the quantitatively-equal-but-qualitatively-different composition of work time creates considerable unevenness in terms of men’s and women’s economic security and mobility.The combination of post-childbirth biology, essentialist gender ideologies, masculinist workplace attitudes, and policy measures designed to enable women, rather than men, to combine employment with caring means that it is still generally the woman in a heterosexual couple who takes time out of the workforce, or goes part-time following the birth of child, whether or not that is her own preference. In the long run this pattern seriously disadvantages women’s opportunities for career advancement, earnings, advancement, and ultimately, pensions. If a man spends more time in paid work than his female partner, he also accumulates more human capital—i.e. more earning power in the long term. And if she stays at home to care for the children, while he works longer hours at his job, the earnings-capability gap widens. This helps to explain why, everywhere we look, we find roughly equal overall work times coupled with gender wage gaps.

Two possible institutional solutions that would promote greater gender equality in both paid and unpaid labor have been suggested. One is to substantially subsidize childcare provision, as in the Nordic model. The other, even more challenging, is to implement statutory reduction of working hours for both partners, in combination with polices supporting genuine work-family flexibility, which would permit couples to stagger their paid work in order to care for their children. This would enable a shorter duration of paid childcare, making it more affordable. It would also allow fathers to spend more time with their children – a desire that is already manifest in the increasing time fathers are spending on childcare and in the fact that their levels of work-family conflict are now higher than women’s, according to the Families and Work Institute, likely reflecting their frustration at not being able to spend more time with their families. A combination of both of these policies helps explain why the Nordic countries continue to perform better than the Anglophone in terms of gender equality, and why, according to the 2013 report of the World Economic Forum, they remain the best countries in which to be a woman.

References

Fisher, Kimberly, and Jonathan Gershuny (2013). Multinational Time Use Study User’s Guide and Documentation Release 6. Oxford, UK: Centre for Time Use Research, University of Oxford.

Kan, Man Yee, Jonathan Gershuny and Oriel Sullivan (2011). “Gender Convergence in Domestic Work: Discerning the Effects of Interactional and Institutional Barriers from Large-Scale Data.” Sociology 45/2: 234-251

Robinson, John (1979) “Toward a Post-Industrious Society.” Public Opinion August: 41-46.

Sullivan, Oriel (2006). Changing Gender Relations, Changing Families: Tracing the Pace of Change. New York: Rowman and Littlefield (Gender Lens Series), pp. 141

Sullivan, Oriel (2010). “Changing Differences by Educational Attainment in Fathers’ Domestic Labour and Child Care.” Sociology 44/4: 716–733

World Economic Forum (2013). The Global Gender Gap Report.

Comments