Although many older Americans have had long marriages, the proportions of Americans over age 50 who have been divorced and remarried have increased substantively over the past 25 years. In fact, individuals in the early ‘baby boomer’ cohort (born between 1946 and 1955) have divorced and remarried more often than any other age cohorts. It is not surprising, therefore, that many multi-generational American families include stepgrandparent-stepgrandchild relationships. This is relevant to multi-generational relationships and perhaps to the future care of these stepgrandparents.

In our studies, we have identified four distinct pathways to becoming a stepgrandparent, and we have conducted a series of investigations designed to uncover how these different pathways affect the formation of stepgrandparent-stepgrandchild relationships. In a recent study we interviewed 48 young adult stepgrandchildren, comparing their perceptions of 44 long-term stepgrandparents who joined the stepfamily before these stepgrandchildren were born, with their perceptions of 28 later-life stepgrandparents who joined their stepfamilies when the stepgrandchildren were late adolescents or young adults). A number of these adult stepgrandchildren had more than one stepgrandparent, and we asked about all of them.

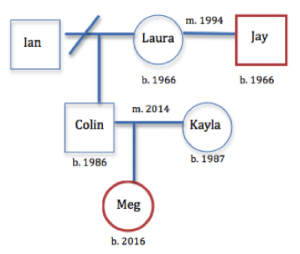

The differences between each pathway have been theorized to result in relationship differences. Long-term stepgrandparents’ are in relationships with stepgrandchildren because they became stepparents when their stepchildren were young – years before those stepchildren reproduced and made them a stepgrandparent. In this figure, Jay is a stepgrandfather to Meg. Jay married Laura in 1994, and Colin became his 8-year-old stepson. As an adult, Colin married Kayla in 2014, and Kayla gave birth to Meg two years later. Jay is a long-term stepgrandfather. As Meg grows up, she will always have had Ian, Laura, and Jay as grandparents on her father’s side of the family (for simplicity, we ignore Kayla’s family tree in this illustration). Jay was a member of Meg’s family long before she was born.

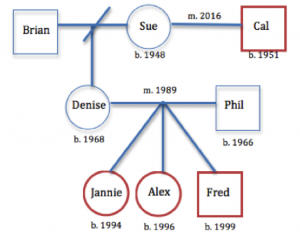

Comparatively, later-life stepgrandparents acquire adult stepchildren and stepgrandchildren following their remarriage to a grandparent; the new stepchildren are often middle-aged parents, and stepgrandchildren are often adolescents or older. The figure is an example of a later-life stepfamily. Cal married Sue in 2016. Sue has a daughter, Denise, who was 48 when her mom remarried. Denise had three children, ranging in age from 17 to 32 when Sue remarried. Those children are now Cal’s stepgrandchildren. Therefore, Cal is a later-life stepgrandfather to Jannie, Alex, and Fred.

The structural factors matter in how multi-generational stepfamilies interact and may affect the quality of stepfamily relationships. We discovered from our interviews that long-term stepgrandparents (like Jay) much more closely resemble biological grandparents in their relationships with stepgrandchildren than do later-life stepgrandparents, and they generally are called by family names (e.g., Grandpa, Nana). In large part this is because of conditions associated with the timing of remarriages and the subsequent personal histories that stepgrandchildren have with biological and stepgrandparents. Although the middle-generation influences how the stepgrandparents and stepgrandchildren bond in both long-term and later-life stepfamilies, parents in long-term stepfamilies control the amount of interactions between the older and younger generations more. Both later life stepgrandchildren and the middle generation adults, because they experience the remarriage of grandparents at the same time, concurrently are grieving the past (i.e., after the death of a grandparent) and trying to make sense of the family transitions. Perhaps not surprisingly, In long-term stepfamilies, relationships and kin connections usually have been defined long ago when the middle generation parents were quite young. The stepgrandchildren did not enter the family until long after remarriage transitions. These long-term stepgrandparent-stepgrandchild relationships and their multigenerational families generally functioned like grandparent-grandchild relationships in first-marriage multigenerational families; later-life families and relationships did not.

The stepgrandchildren did not remember a time when their stepgrandparent had not been a part of the family. Similar to findings from previous research, our results suggest that contextual factors, namely the timing of life events and transitions, duration of key family relationships, and opportunities for intergenerational interaction (e.g., co-residence, affinity-building), matter tremendously for if, how, and to what extent, intergenerational steprelationships are developed, maintained, and associated with caregiving and support exchanges, particularly in later-life.

Results from our study suggest that later-life stepgrandparents may be especially at risk for diminished social support, particularly from adult stepchildren and stepgrandchildren. These relationships often did not have enough time to develop before the older stepgrandparent needed care or other help. The later-life stepgrandparent had not had time to do things that bond people together – hanging out, giving gifts and sharing resources, having fun together. As a result, younger generations did not feel a sense of obligation or a need to reciprocate past gifts of the later-life stepgrandparent. The stepgrandchildren and their parents often referred to the later-life stepgrandparent as “grandma’s new husband” or “grandpa’s new wife.” Although stepgrandchildren’s thoughts and feelings about long-term and later-life stepgrandparents are worth exploring and shed light on complex family processes, we are unable to draw conclusions about the experiences of middle-generation parents or stepgrandparents. Because individuals experience family transitions differently, and these transitions, in turn, inform kinship ideologies and family interactions, more research is needed to glean the perspectives of family members from multiple family roles. Analyses of qualitative data garnered from multiple perspectives (e.g., biological grandparents, biological parents, stepgrandparents) would offer additional insights about family transitions and relationship trajectories. Data from more diverse multigenerational stepfamilies would also add to our knowledge base, as most of our respondents self-identified as White and ‘middle-class.’ Moreover, some stepgrandchildren were reporting on relationships with deceased stepgrandparents. Although the degree to which the death of stepgrandparents influenced stepgrandchildren’s narratives about their family relationships remains an empirical question, it is possible that interviews about dead relatives may differ in important ways from interviews about living relatives. Finally, family relationships and dynamics, including roles/rules, symbols, and language, are likely to vary across cultures, yet we are unable to speak to the influence of culture on intergenerational steprelationships given the cultural homogeneity of our sample.

This study has moved beyond describing stepgrandparenthood pathways to exploring underlying processes in intergenerational relationship building. Relationship quality among stepgrandparents and stepgrandchildren may vary widely, regardless of pathway. We have illuminated here the dynamics by which these distinct types of intergenerational stepfamilies diverge. Researchers and practitioners who work with older stepfamilies can utilize this knowledge to better think about, work with, and support stepgrandparents in later life. For researchers, knowing about pathways to stepfamily status (i.e., “How did they get here?”) provides hypotheses or assumptions to explore. In future studies of stepgrandparents, we encourage researchers to consider and attend to structural pathways, as the variability of stepgrandparent “types” is often an overlooked, yet important, distinction. For practitioners, understanding if, how, and to what extent stepgrandchildren’s relationships with stepgrandparents impact both upward and downward exchanges of social support, particularly as stepgrandparents age, can be useful in working with families to create care plans for older adults in later-life. Issues of who will care for frail stepgrandparents can only be addressed effectively by an understanding of the diversity of multigenerational stepkin relationships. Moreover, understanding pathway implications to stepgrandparenthood can enhance science and practice with older step-couples. Our findings illuminate expectations about new partner involvement in family life following transitions such as death, divorce, and remarriage.