Part 3 of the Overparenting Series

My previous posts offered an introduction to metaphors used in three different national contexts in order to lay a foundation for my claim that both the concept of overparenting and the words used to describe it are culturally constructed. I also introduced the historical and disciplinary origins of the metaphors. The next paragraphs identify important sociological threads that tie together the obsession with American helicopter parents, Danish curling parents, and British lawnmower parents.

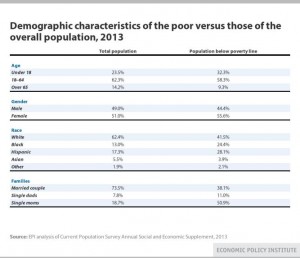

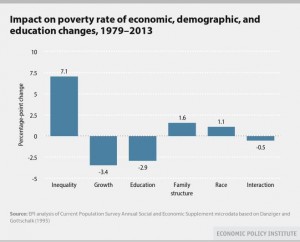

Anxiety, Social Class, and Overprotection. Despite the differences between the metaphors, all of them are about parents who have the means to enact them. In most of the sources referenced here, authors are quick to point out that it is primarily affluent parents who are transforming into helicopters, sweepers, and lawnmowers. The effort put forth for the sake of protecting children and preparing them for the world is recognizable as a form of cultural capital that only the select few have the resources to enact (and the resources to read and talk about), something that sociologist Annette Lareau has discussed in her work on middle class parents’ efforts to intentionally cultivate skills in their children. But even as affluent parents make the efforts to protect their children, the ideals associated with being a “good parent” spread to all parents regardless of class.

In addition to the class-based popularity of overprotective parenting, the metaphors connote anxiety in a sea of saturation of bad, good, and in-between information. As sociologist Margaret Nelson has written in her book Parenting Out of Control: Anxious Parents in Uncertain Times, today’s parents, especially ones with means, are overwhelmed with metaphors, messages, and scary clip art about effective parenting. The metaphors lead to a damned-if-you-do, damned-if-you-don’t world. Parents feel inadequate in their seemingly excessive (class-based) efforts to try to curtail the perceived dangers that lurk around the corner for their children. And feel anxious about whether their impulse to protect is messed up, too.

If we think about the metaphors used, they are meant to convey protection, but they can create unforeseen problems. Indeed, these layers of action that the images suggest is why metaphors are particularly compelling, and why the types of parents they represent can be deemed as both good and bad. The helicopter can rescue, but it can also blow away the prized scarf. The sweeper can smooth a path, but also carve too shallow a spot in the ice that leads the stone to the edge. The lawnmower can clear the blades, but also propel itself into the flowerbed where the spiders live. The metaphors evoke the infinity of “what if” moments that could make anyone have butterflies in the stomach, in terms of both success and failure of the image. Maybe that scarf is ugly. Maybe the stone needs to find the edge before it gets back on track. Maybe spiders are interesting creatures to spend time getting to know. In other words, the collateral damage may be harmless, or it may even simply be not harmful at all to begin with.

Admittedly, creating the best designed fuselage, studying the science of ice brushing, and inventing a stop button on a self-propelled lawnmower are reasonable pursuits to enhance actual helicopter flying, curling, and lawnmowing. But these pursuits done in the name of preventing imaginary things or things inaccurately defined as negative, or done so that parents can have yet more scary imagery in their anxiety arsenal, doesn’t seem to be a good use of time and resources.

MY VIEW: We spend time thinking about the quality of other people’s parenting because other people’s children may affect our child; because thinking about others’ parenting affects how we assess our own parenting; and because it matters beyond our families to locations as large as the nation-state. After all, it’s not hard to find opinion pieces on how a particular country is faring, given the characteristics of the youngest generation. Or on how some parents who are trying to instill the asset of autonomy in their children are reported as UNDERdoing it, thus offering commentary on the role of the state, the neighborhood, and the voyeuristic role of other parents. In other words, the act of assessing the quality of other people’s parenting is contextualized by important sociological factors. What I hope to add is that the words used to describe all of this also need context, too.

Art Gallery of Advice. At the risk of subjecting myself to my own critique about both parenting advice and social class inequality, I offer here another metaphor. But this time, the parent and the child are not metaphors. The parenting advice is. What if each parenting advice column and conversation was an art piece hanging on a wall? What if the world in which parents try to operate is the art gallery? There’s a reason art galleries allow a lot of space between pieces. The space allows the viewer to absorb the art with little distraction and enough time, so that she can uncover the art piece’s story and context, and can decide whether it’s worth looking at longer, ignoring, or obsessing over until she buys a copy for her own home.

Why not take a step back and look into the entire gallery, in order to recognize that we often find ourselves in front of a cluttered wall of parenting advice? Wall clutter that contains different artists competing for the most clever use of metaphorical imagery or best use of genre or media, and different nations competing over who has submitted the best art. Why not take a step back and look at the gallery-goers, recognizing that their artistic preferences are all influenced heavily by their cultural context? Heck, why not recognize that art galleries are classed, and not everyone has time to visit one or care whether it exists?

Imagine a gallery where there was no white space, and the space between crowded pieces was filled with mirrors etched with superimposed scary images. Like viewers in an art gallery who are well-served with calm space between art pieces, parents can benefit from less, not more. Let’s stop making so much clutter, or at least help viewers realize that they can ignore it and just focus on the art that brings them joy and just the right amount of challenge. I encourage people to remember that actual children and parents are not metaphors. What I would like us to realize is that our preoccupation with turning them into metaphors is very real, and could use a careful calm stroll through the gallery of information so that we can best choose what art makes us feel the best about our amazing (and yet, totally mundane) role as parents.

Michelle Janning is Professor of Sociology at Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington, and serves as Co-Chair of the Council on Contemporary Families. She has taught and served as a pedagogical consultant for the Sociology and Child Development and Diversity programs at the Danish Institute for Study Abroad. She also let her son ride public transportation in Copenhagen by himself when he was eight years old. More about her can be found at www.michellejanning.com.