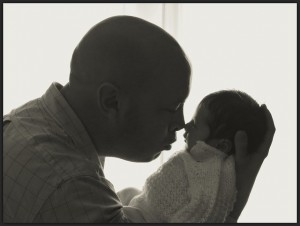

U.S. fathers are eager to be more involved in the care of their infants and young children—per much research and

many people’s personal accounts. The New York Times recently reported on men who have pursued legal action against their employers as a challenge to discriminatory policies and practices that prevent or limit the time they have available to utilize parental leave. Additionally, a recent survey of American fathers found an overwhelming majority, 89 percent, rated paid parental leave provided by an employer as an important workplace benefit. But consider this: there is also significant evidence that men are not likely to use parental leave, even when it is paid.

Because the leave mandated by the 1993 Family and Medical Leave Act is unpaid (and simply unavailable to many Americans), many fathers can’t use it due to financial constraints. If paternity leave was paid, and resulted in no lost income, would men be more likely to take it? In our current economic climate, the answer is not so clear. My recent research on men in academia reveals that many fathers are uninterested, hesitant, or fearful that if they step away from their workplaces for most or all of the 15 weeks their employer offers in parental leave, their careers will suffer.

Some people think that academic institutions are paragons of research, discovery, and innovation that would, of course, be on the leading edge of progressive policies that would allow employees to balance the needs of work and family. This, however, is not the case. Few colleges and universities offer paid leave for mothers that doesn’t require the use of sick or vacation time to cover lost wages, and many schools actually violate federal law with their parental leave policies. Fewer still extend parental leave benefits to fathers. Furthermore, the tenure process puts pressure on young faculty, those who might be looking simultaneously at the tenure clock and their biological clocks. And the vulnerability of some staff positions or the demands on administrators means they are also not likely to take any extended leaves for the birth or adoption of a child.

Originally impressed by the decade long policy of gender neutral parental leave at the institution I recently studied, I ultimately found that policy and practices were seldom in alignment. Through interviews with men, both faculty and staff, employed in higher education within an institution with a generous parental leave policy, I learned that the opinions of colleagues and the needs of co-workers often took precedence over the wishes of a spouse and the needs of a new baby. In general, the men I interviewed still defined a significant part of their family role as that of provider, regardless of their partner’s employment status. Even though a policy of parental leave existed, and even though many of the women with whom they worked had utilized the leave, many fathers worried about the future consequences for their careers if they took any significant time out for parenting. Would co-workers resent them for taking the time off and possibly burdening colleagues with additional responsibilities? Would supervisors question their commitment to their careers or the institution? Would they lose future opportunities or rewards in their workplace if they took parental leave?

Without a doubt, we need more realistic and generous policies that allow workers, men and women, to meet the needs of their families and their workplaces. But people also need to use the policies that are available. The fact that this workplace offered a policy, but few men felt they could use it without suffering consequences, demonstrates the power of the workplace culture and the resistance many employees feel to rocking the boat, especially following a period of economic tumult. Moreover, when it is largely women who utilize parental leave, we reinforce gendered patterns of care work and continue to disadvantage women in the workplace.

These and other issues related to the individual and institutional factors that influence combining paid work and care work in academia are examined more closely in a collection I recently co-edited with Catherine Richards Solomon, Family Friendly Policies and Practices in Academe.

Erin K. Anderson is Assistant Professor of Sociology at Washington College. Her research focuses on the experiences of gender at individual, interactional, and institutional levels. Her most recent work appears in Family Friendly Policies and Practices in Academe.