Reprinted from Chicago Tribune.

Feminists my age and older — I’m in my late 50s — have been shocked to find how few young women are as excited as most of us by the prospect of having a female president. We grew up in a world where there were no powerful female role models — in politics, business or even in the movies — and where we were sternly warned against entertaining any aspirations of our own. We were expected to find our sense of achievement and meaning in the accomplishments of our future husbands and sons. Betty Friedan famously described how “the feminine mystique” forced women and girls of that era to conform to stifling stereotypes that caused long-term damage to their self-esteem and happiness. What a thrill it is, for many of us, regardless of our personal politics, to see a woman so close to smashing the stereotypes that held us back for so long. And why, we wonder, can’t young women see what it would mean for women everywhere to have such a role model?

But maybe at this moment in history we are looking to the wrong sex to find people who feel the anguish that gender stereotypes can cause. At this moment, could boys need gender equality even more than girls?

It’s no accident that the older women berating millennials’ supposed lack of feminism are in their 60s, 70s, and 80s. These women grew up in an era when gender stereotyping was so pervasive it organized the course of every woman’s life, whatever her class, race, education or politics. Being a woman colored every aspect of life, and every choice to be anything more than a wife required us to defy powerful social norms. During the consciousness-raising meetings of the 1970s and 1980s, almost every young woman had a story about the pain she had felt when told that she wasn’t “being a lady” or worse still, was “acting like a man.”

That’s changed for young women. In my interviews with millennials for a forthcoming book, I found that it was the young men, not the young women, who told painful stories about their experiences with gender stereotyping. Feminism has so changed the world that young women no longer feel constrained in their girlhood even during their transition to adulthood. Research suggests gender consciousness will develop later of course, as women face the motherhood penalty at work and the growing pay gap with men as they age. But right now, everyone tells them “you go, girl.”

But if gender is invisible to most girls transitioning to adulthood, it is all too real to the boys who still get bullied for not “being a man” or for “acting like a girl.” I heard stories that turn my stomach about young men being teased for wanting to take a ballet class, or ridiculed in their adolescence because they’d rather hang in the kitchen with their sisters than play football with the guys in the family. Girls are increasingly allowed the freedom to be anything they want to be, but boys are still pressured to “man up.” As Stephanie Coontz, a historian and director of research for the Council on Contemporary Families, suggests, “Gender stereotyping of women is still real, but it tends to kick in after a woman leaves school and starts trying to combine her personal life and work life. It’s OK now for a girl to be a tomboy or an athlete or a great student. But the gender-typing of boys kicks in very young, and the penalties for gender-nonconformity are harsh.”

At this point in millennials’ lives, in this feminist-influenced you-go-girl world, young women understand gender to be a personal attribute, not a socially imposed identity. Why would they support a woman for president because she shared their sex category? The millennial women in my sample mostly claim never to have experienced sexism, and even if they may in the future, that’s not going to affect their votes now.

Perhaps a candidate who wants to open up opportunities that are limited because of sex should start talking to male millennials who increasingly express discontent with the pressures to be the primary breadwinner and not to take time off at work when they have a new baby at home or need to be available to help their mother die in her own home, with dignity. Young women feel they have the option to have a full-time career but also to cut back if they feel the need (at least if they are married to partners with incomes) but men do not. Men are beginning to resent the freedom women have for “choices” when they have none.

Perhaps Hillary Clinton should explain to young men how much better off they would be if they had a female president who appreciates their desire for a more balanced life than the masculine mystique allows. They may now be more ready to listen than are the young women who still labor under the illusion that they can have it all without men’s lives changing.

Barbara J. Risman, a professor of sociology at the University of Illinois at Chicago, is on sabbatical at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University. She is also a senior scholar at the Council on Contemporary Families.

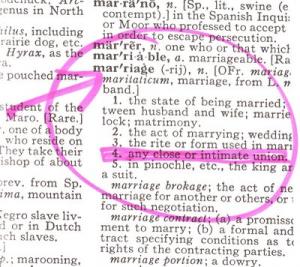

It is challenging to untangle contemporary definitions of marriage from definitions of wife and husband. Wife is a noun, defined in relation to another. According to Merriam-Webster dictionary, wife means “the woman someone is married to.” Wives often take on adjectives such as military wife, political wife, housewife, and so on.

It is challenging to untangle contemporary definitions of marriage from definitions of wife and husband. Wife is a noun, defined in relation to another. According to Merriam-Webster dictionary, wife means “the woman someone is married to.” Wives often take on adjectives such as military wife, political wife, housewife, and so on.