Arielle Kuperberg, Assistant Professor of Sociology, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, is author of this week’s briefing report at CCF@TSP. Here she answers the questions that keep coming up when people talk about cohabitation these days.

Lots of people keep asking, Does living together before marriage increase your chance of getting a divorce? In my recently published study, I finally answer this question with a definitive “no!”

For decades, researchers have found a connection between premarital cohabitation and divorce that no one could fully explain. Despite these studies and warnings from well-meaning relatives about the dangers of “living in sin,” rates of living together before marriage have skyrocketed over the past 50 years, increasing by almost 900% since the 1960s. I found in my study that almost two-thirds of women who married between 2000 and 2009 lived with their husband before they tied the knot.

With the majority of couples now living together before marriage, if cohabitation somehow caused couples to divorce, you would think that divorce would be more common in recent generations of young adults, who were much more likely to live together before marriage compared to earlier generations. But recent research has found that for young adults born in 1980 or later, divorce rates have been steady or even declining compared to earlier generations.

What explains the connection between cohabitation and divorce?

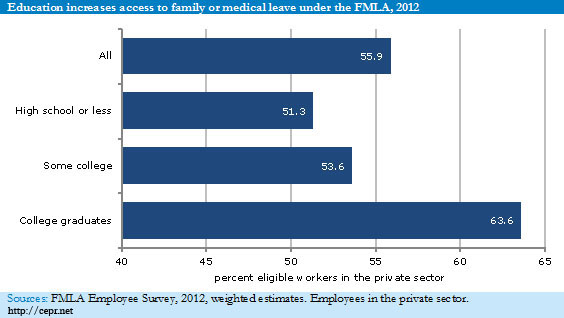

We already knew that some of the connection between cohabitation and divorce is a result of the type of people who live together before marriage. In my study I find that compared to those who married without living together first, premarital cohabitors have lower levels of education, are more likely to have a previous birth, and are more likely to be black and have divorced parents, all factors that numerous studies (including mine) have found are related to higher divorce rates.

My study found that the rest of the connection between divorce and cohabitation can be explained by one thing that previous researchers never took into account: the age at which couples moved in together. Cohabitors moved in together at earlier ages (on average) than couples that didn’t live together before marriage, and since living together at younger ages is associated with higher divorce rates, cohabitors are more likely to divorce.

Why does moving in when you are younger increase your divorce rate?

Younger couples are (on average) less prepared to run a joint household together, and may be less prepared to pick a suitable partner than couples that settle down when they are older (on average- remember this doesn’t apply to every couple!). People change a lot in their early 20s, and those changes sometimes cause incompatibilities with a partner who was selected at a younger age. These incompatibilities lead to higher average divorce rates among those who moved in with their eventual spouse at a young age, even if they waited to marry until they were older.

My research shows that waiting until you are 23-24 or older to settle down with a partner is associated with around a 30% risk of divorce if you marry that partner. Moving in earlier leads to a much higher divorce risk- for instance couples that move in at age 18-19 face almost a 60% risk of divorce if they eventually marry, and couples aged 21-22 when settling down have a 40% risk of divorce after marriage.

Are cohabitation and marriage different types of relationships? Why get married at all?

A frequent question I’ve been asked is: does this mean cohabitation and marriage are basically the same? One reporter asked me about a recent study in which couples were threatened with a mild electrical shock while holding the hand of their married or cohabiting partner, where married couples were shown to be calmer than cohabiting couples. Doesn’t this show that cohabitation is a different type of relationship than marriage is?

Absolutely! My own research has shown that although cohabitation and marriage aren’t drastically different types of relationships for couples that lived together before marriages, some differences in behavior are pronounced, and the longer a couple has been married, the greater these differences grow. The public commitment, legal binds, and social expectations that come with marriage affect behavior in numerous ways which can’t be discounted.

So should you live together before marriage? Should you get married at all? That’s up to you! But living together won’t increase your chances of getting a divorce if you choose to go that route.

![By Irangilaneh (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://thesocietypages.org/families/files/2014/08/Back_to_school-150x150.jpg)

![Ashton Applewhite hosts *This Chair Rocks.* By Clipper (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://thesocietypages.org/families/files/2014/07/257px-Rocking_chair_instable.svg_.png)