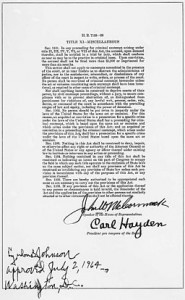

In February, I edited a Council on Contemporary Families three-day online symposium marking the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Civil Rights Act. This week on July 2, we celebrate 50 years since its enactment. The section of the symposium that focused on changes in racial-ethnic relations included papers that addressed the emergence of Latinos as the largest “minority” in the United States, the approaching eclipse of the white majority, the increase in interracial marriage and multiracial families, and the progress that has and has not been made in lessening the inequities historically associated with non-white status. Download the .pdf here from CCF. Here are a few highlights.

New Demographic Realities

In 1964, race relations, like television shows, were still largely viewed in black and white. As author Raha Forooz Sabet notes in “Changes in America’s Racial and Ethnic Composition Since 1964,” at that time, 85 percent of the population was white and 11 percent black. Latinos were less than four percent of the population, and fewer than six percent of U.S. residents were foreign-born.

Today half of all children under the age of one are ethnic and racial “minorities,” and within 40 years, non-Hispanic whites will account for just 47 percent of the population. There are now as many foreign-born as black Americans.

By 2060, according to University of Texas-San Antonio researcher Rogelio Sáenz, the single largest component of the child population of the U.S. will be Latino. In his paper, “The State of Latino Children,” Sáenz discusses the characteristics of these Americans, who will soon become the most numerous single group of students, voters, workers, and consumers. Latinos overall have below-average levels of educational attainment, in part because of low levels of preschool enrollment. However, it is a myth that Latino youth are not learning English. Three-fifths of Latinos aged three to 17 are bilingual, speaking Spanish at home but also fluent in English. Only four percent of all Latino children and less than 12 percent of those who are foreign-born are unable to carry on a conversation in English.

More than one-third of Latino children live in poverty. Having two married parents is less protective for Latino children, in terms of income, than it is for white and black families. Nearly one-quarter of children in Latino married-couple families are poor.

But Sáenz highlights an “epidemiological paradox” in the Latino community. Despite higher than average poverty rates, Latino children are healthier than average and have a longer life expectancy at birth than either white or black babies. Sáenz argues that determining the source of this cultural advantage is as important as finding ways to help Latino children overcome their educational and income disadvantages.

The Good News: Old Prejudices are Lessening and Many Old Boundaries Have Been Broken Down

Discussing the changing prospects of African Americans (“Are African Americans Living the Dream 50 Years after Passage of the Civil Rights Act?”), Velma McBride Murry and Na Liu of Vanderbilt University note real breakthroughs for a significant portion of that population. The number of elected black officials in the country has skyrocketed, from about 100 in 1964 to 10,000 in 1990, and today we have an African-American president in his second term. There is now a substantial African-American middle class. Indeed, one in ten black households earns $100,000 or more a year.

One dramatic change, Kimberlyn Fong points out in “Changes in Interracial Marriage,” is the revolution in attitudes toward interracial marriage. When the Civil Rights Act was enacted, less than five percent of Americans approved of interracial marriage. Today 77 percent approve of such marriages, an all-time high. Since the early 1960s the number of new marriages contracted each year between spouses of a different race or ethnicity has increased sixfold.

Fong documents interesting differences among racial-ethnic groups in the extent of interracial marriage and in its gender makeup. Among recent marriages, the most common interracial matches are white/ Hispanic couples. The second most common is between whites and Asians. However, Asian women are more than twice as likely as Asian men to marry outside their race.

The sex ratio skews in the opposite direction in marriages between blacks and whites. But black-white marriages remain the least common interracial marriage, accounting for 12 percent of new marriages in 2010. And that brings us to the bad news.

Despite the Movement of Some Blacks into the Upper Echelon of Political and Economic Life, the Majority Still Bear a Heavy Legacy of Disadvantage

African Americans have experienced significant declines in poverty and increases in access to middle-class jobs. Yet through almost the entire half century since passage of the Civil Rights Act the black unemployment rate has consistently remained twice as high as that of whites, and the poverty rate has been more than twice as high.

After declining in the 1970s, school segregation has increased again. Residential and economic segregation also remain strong. Among Americans born between 1985 and 2000, 31 percent of blacks, versus only one percent of whites, live in neighborhoods where 30 percent of the residents are poor.

African Americans have greatly increased their educational achievement over the past 50 years. But at every educational level, blacks earn less than whites with the same educational credentials.

And racial discrimination remains widespread. African-American men are far more likely to be arrested and to receive longer sentences than whites who commit the same offenses. A study of the low-wage job market in New York City found that white applicants were twice as likely as equally qualified blacks to receive a callback or job offer. White applicants who had just been released from prison were as likely to get a callback or job as black and Latino applicants with no criminal record!

These examples suggest a growing class polarization within the African-American community, alongside the continuing gap between the average fortunes of blacks and whites, with an elite group pulling away from the larger number of blacks who continue to experience racial profiling and deeper levels of poverty than whites. This raises the troubling possibility that the progress of one sector of the African-American community provides many Americans with an excuse to ignore the historical legacy of segregation and the persistence of racial discrimination for the black population as a whole.

Stephanie Coontz is Co-Chair of the Council on Contemporary Families.