This is the fourth part in a series about how girls and women can navigate a culture that treats them like sex objects. See also, parts One, Two, and Three. Cross-posted at Caroline Heldman’s Blog.

This post details some daily rituals that help interrupt damaging beauty culture scripts.

1) Start enjoying your body as a physical instrument.

Girls are raised to view their bodies as an thing-to-be-looked-at that they have to constantly work on and perfect for the adoration of others, while boys are raised to think of their bodies as tools to use to master their surroundings. We need to flip the script and enjoy our bodies as the physical marvels they are. We should be thinking of our bodies, as bodies! As a vehicle that moves us through the world; as a site of physical power; as the physical extension of our being in the world. We should be climbing things, leaping over things, pushing and pulling things, shaking things, dancing frantically, even if people are looking. Daily rituals of spontaneous physical activity and thanks for movement are the surest way to bring about a personal paradigm shift from viewing our bodies as objects to viewing our bodies as tools to enact our subjectivity.

Fun Related Activity: Parkour,”the physical discipline of training to overcome any obstacle within one’s path by adapting one’s movements to the environment,” is an activity that one can do anytime, anywhere. I especially enjoy jumping off bike racks between classes while I’m dressed in a suit.

2) Do at least one “embarrassing” action a day.

Another healthy daily ritual that reinforces the idea that we don’t exist to be pleasing to others is to purposefully do at least one action that violates “ladylike” social norms. Discuss your period in public. Eat sloppily in public, then lounge on your chair and pat your protruding belly. Swing your arms a little too much when you walk. Open doors for everyone. Offer to help men carry things. Skip a lot. Galloping also works. Get comfortable with making others uncomfortable.

3) Focus on personal development that isn’t related to beauty culture.

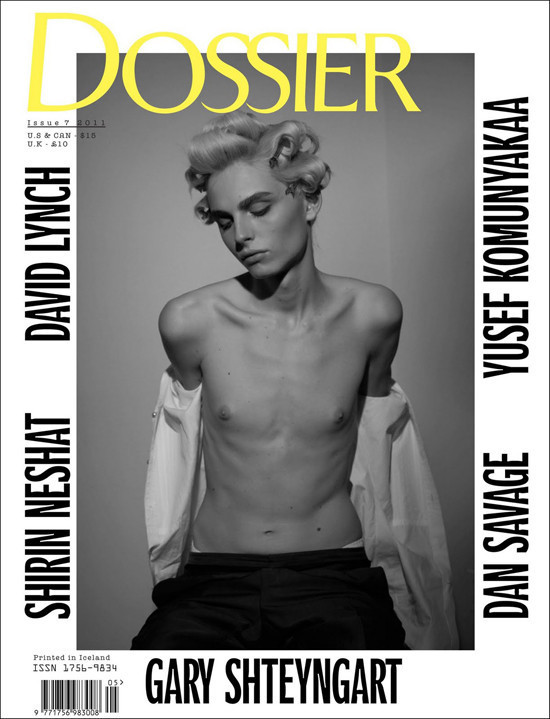

According to research, women spend over 45 minutes to an hour on body maintenance every day. That’s about 15 more minutes than men each day and about 275 hours a year.

But, since you’ve read Part 3 of this series and given up habitual body monitoring, body hatred, and meaningless beauty rituals, you’ll have more time to develop yourself in meaningful ways. This means more time for education, reading, working out to build muscle and agility, dancing, etc. You’ll become a much more interesting person on the inside if you spend less time worrying about the outside. The study featured above showed that time spent grooming was inversely related to income for women.

4) Actively forgive yourself.

A lifetime of body hatred and self-objectification is difficult to let go of, and if you find yourself falling into old habits of playing self-hating tapes, seeking male attention, or beating yourself up for not being pleasing, forgive yourself. It’s impossible to fully transcend the beauty culture game since it’s so pervasive. It’s a constant struggle. When we fall into old traps, it’s important to recognize that, but quickly move on through self forgiveness. We need all the cognitive space we can get for the next beauty culture assault on our mental health.