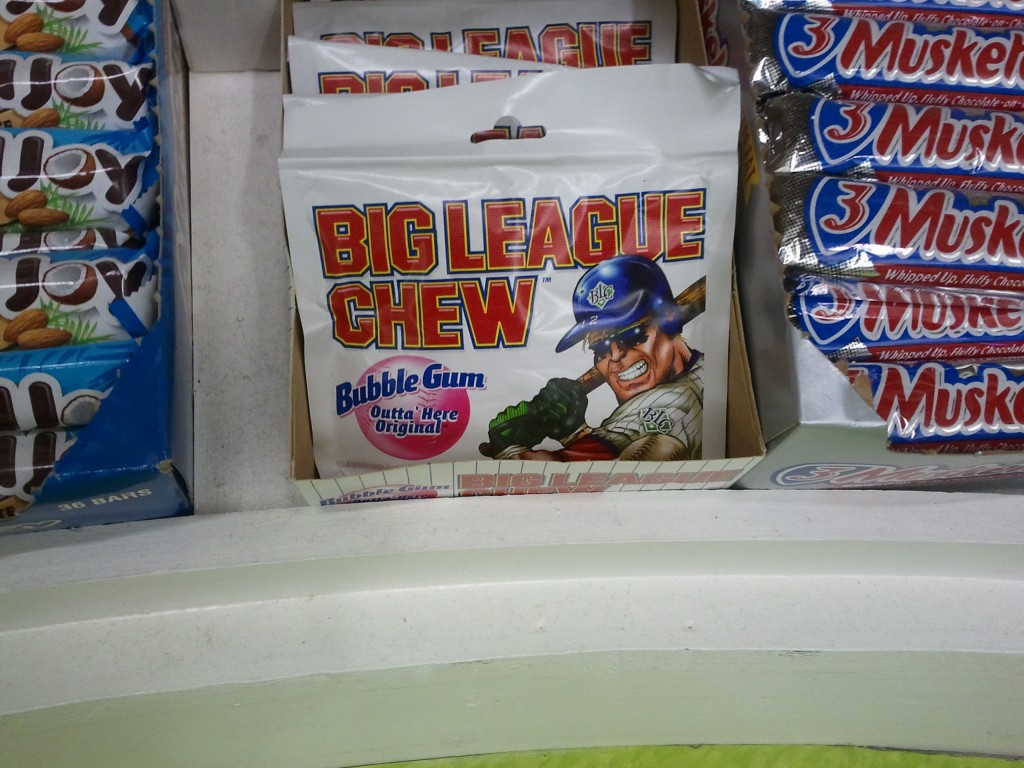

Last week I stopped in the candy store on State St. in Madison, WI only to discover a product that I remember consuming as a kid, but thought had been banned in the U.S. years ago: tobacco-themed candy.

According to wikipedia, candy cigarettes (I’m not sure about the other products) are banned in Finland, Norway, Ireland, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia; Canada has banned packaging that resembles real cigarettes. A U.S. ban was proposed in 1970 and again in 1991, but it failed to pass in both instances.

I do remember feeling cool, as a kid, when I pretended to smoke them.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.