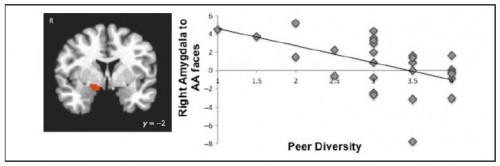

New neurological research, reported by Robert Wright at The Atlantic, suggests that racism is learned. Earlier studies had shown that the amygdala, “a brain structure associated with emotion and, specifically, with the detection of threats,” is active, on average, when White people see Black faces.

A new paper, however, led by Eva Telzer, shows that we don’t see this reaction until about age 14. Moreover, how powerfully it is after the age of 14 depends on the racial composition of your peer group. White people who grow up in more diverse environments show a much weaker reaction than those in homogeneous ones.

This figure illustrates the difference. As peer diversity increases, reaction of the amygdala retreats to zero.

This is what it means, Wright explains, to say that race is a social construct:

It’s not a category that’s inherently correlated with our patterns of fear or mistrust or hatred, though, obviously, it can become one. So it’s within our power to construct a society in which race isn’t a meaningful construct.

For lots of examples of why race is socially constructed, see our Pinterest board on the topic.

And, for other super cool stories about biology, see language, culture, and color; a story of human echolocation; human brain synchronicity; and men with higher voices have higher sperm counts.

Originally posted in 2012. Re-posted in solidarity with the African American community; regardless of the truth of the Martin/Zimmerman confrontation, it’s hard not to interpret the finding of not-guilty as anything but a continuance of the criminal justice system’s failure to ensure justice for young Black men.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.