Minimalism has a way of latching on to people that want nothing to do with it. None of the artists contained in Kyle Chayka’s Longing for Less wanted to be associated with the term, and yet here they are, mostly posthumously, contained in a book subtitled Living with Minimalism. Chayka nevertheless pulls together midcentury artists like Philp Glass and Donald Judd and contemporary pop culture icons like Marie Kondo and the author of the 2016 self-help-through-minimalism book The More of Less Joshua Becker into a single, slim volume against their will.

Objections to having your work defined as “minimalist” come out of a desire to use art to point to the maximal things that are not contained within the minimalist work— the majesty of the universe, the stirring sounds of an audience, a contemplative desert expanse are the real subjects. The frustration is understandable: Imagine if you underlined an important passage in a book, handed it to someone else, and their only reply was, “Interesting that you chose to use pencil to draw that line. Is this about the impermanence of thought?” This is the plight of the so-called minimalist artist. Their art was meant to be so straightforward and devoid of metaphor or allusion that the observer would have no choice but to consider the implications of whatever is right in front of them— whether that’s a pile of dirt hiding in a New York City loft (The Earth Room, by Walter De Maria, 1977) or a collection of metal cubes in Marfa, Texas (100 untitled works in mill aluminum, by Donald Judd, 1982-1986).

Most minimalists seem unhappy with wherever they find fame, whether that’s 1970s SoHo or Paris, or Japan. As soon as their talents could be translated into you-come-to-me stardom, they left for someplace else. Chayka is determined to give each minimalist on their own terms describing their careers with deference, even the Nazi-sympathizing architect Philip Johnson gets to be something more complicated than just that. He’s also an exhibitionist neighbor, the originator of the term “International Style”, and a certified (by the FBI, actually) hottie. It’s the right choice for a book whose stated mission is to “figure out the origins of the thought that less could be better than more—in possessions, in aesthetics, in sensory perception, and in the philosophy with which we approach our lives.” Considering a broad range of work on its own terms goes a long way towards understanding what Chayka calls his “working definition of a deeper minimalism” which is an “appreciation of things for and in themselves, and the removal of barriers between the self and the world.“

At the end of a chapter there’s a short anecdote about Johnson’s first night in The Glass House, a small home made up of just a few steel beams to support walls of glass. Johnson walks into the house at night and upon turning on the lights finds that the glass acts as a mirror more than a lens. He calls an associate and yells: “You’ve got to come over immediately. I turned on the lights and all I see is me, me, me, me, me!” They solve the problem by setting spotlights outside on the trees, such that more light comes in from the outside than is reflected in glass. Chayka doesn’t say as much but from what I gather from the rest of the book, this is a metaphor (or maybe a Zen koan?) for all minimalist works: in an attempt to strip everything away and catch an unimpeded glimpse of the world all you end up with is an unwelcome picture of yourself. The artist’s reaction is always to change the scenery instead of feeling more comfortable with themselves where they are.

The artists are not alone in finding out, once the work is completed, that their works draw attention to the wrong things: the work itself or the artist instead of some deeper truth. This is a fairly common problem with casual consumers of art, though most people articulate it as being picky about what art they deem important. Someone can shout “my kid could make that” in a modern art gallery and then melt down the next day when they learn someone didn’t stand for the national anthem. Both the modern art hanging in a museum and a rendition of the national anthem at a ball game are works of art, but their stated values and contexts are shot through with different and at times contrasting socio-economic identifiers. Pierre Bourdieu used the word “distinction” to refer to this nexus of social position, economy, and cultural interpretation. We learn to appreciate and decode cultural objects in a social way, ascribing political valences to both their intended audiences and the artifacts themselves. You already understand this implicitly: think of the stereotypes of who enjoys opera versus NASCAR and Bourdieusian distinction immediately makes sense.

It is clear that Chayka and I do not have the same distinction. He describes watching Lost in Translation for the first time at age 15 as a transformative moment. I remember checking it out thinking a Bill Murray movie would be funny and being sorely disappointed. Even though the Massachusetts Museum of Modern Art is less than an hour away from me I have never been there. I lack both the interpretive schema and social pressures that makes going there enticing. Ditto most symphonies and things described as “experimental.” I don’t even like poetry very much. This makes me uniquely qualified to review The Longing for Less though, as it was written for a broader audience as an introduction to this material. My interest in the book is not propelled by a love of Philip Glass, John Cage, Richard Gregg, Shūzō Kuki, or Agnes Martin. I didn’t even know who Donald Judd was until reading this book. My sole motivation is to understand that “deeper minimalism” Chayka is after and if that takes me through a bunch of stuff I don’t find particularly interesting, so be it. This is minimalism in action: looking at a greater whole with the help of something direct and unsettling. To review this book is not only to review the argument printed on the page, but the actual thing itself.

—

My copy of The Longing for Less arrived in the mail just as I was lapsing into an extended fit of sadomasochism that took the form of watching The West Wing for the first time. There’s an episode in the third season where someone named Tawny is arguing with Sam Seaborne over the national endowment for the arts funding. Tawny keeps spitting artworks at Sam— “’Slut’ is a one-word poem by Jules Woltz. It’s stamped in scarlet on a piece of forty by forty black canvas.”— as if their descriptions alone make her argument: aren’t you mad your government spent money on this?! Sam calmly agrees that these examples of art are embarrassing but disagrees fundamentally with government assessing the value of the resulting art once the artist has been funded. It is a great example of the liberal mind at work: having values but mistaking them as mere opinions not worthy of connecting to the power you wield.

Perhaps it is through sheer force of serendipitous juxtaposition that The West Wing and The Longing for Less kept bumping into one another in my head. Like Johnson rejecting the reflection in his own creation, I was catching glimpses of myself in both pieces of media: values I once espoused, desires long extinguished, and half-forgotten memories of past realities. I caught myself having a Sorkin-esque dialogue in my head when reading about Walter De Maria’s The Earth Room. Why did the microbes contained within the 250 cubic yards of dirt have better living conditions than the 70,000 homeless people in the same city? Well, if we waited to solve all human needs before making art then what kind of society would we really be living in? Yes, but this kind of art? Who’s to say what art gets to be made? Yeah, but this dirt has been living in the same SoHo loft since 1977— how many humans have that kind of security?! And so on.

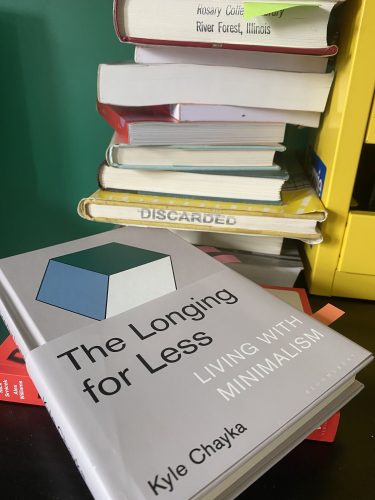

Closing The Longing for Less does not stop it from broadcasting its thesis. The book is clearly a thoughtfully designed object, meant to participate in the minimalist project it seeks to understand. In an interview with Delia Cai, Chayka says he “wanted the book itself to be a minimalist object, a visual representation of what the book was about.” Designed by Tree Abraham —whose work could be described as minimalist— the dust jacket only comes up halfway but it contains the title and author. On the hardcover is a cube sitting on edge with its three visible faces of white, hunter green, and sky blue. However, once the jacket is removed, the cube is revealed to be part of a longer shape. The white extends down into a parallelogram and the blue and green —now they are more recognizable as diamonds— are mirrored on the opposite side of the single white shape. The text is now confined to the spine.

Never have I actually wanted to see a book age as much as this one. To see how the pure white center yellows, whether people keep the dust jacket at all. I want to order it for my university library just to see what they do with it. Do you keep the dust jacket in place with the usual archivist tape and plastic or do you put it on the shelf naked? Mine has already creased quite a bit and I find the book hard to hold with it on so I suspect most people will lose it if they don’t intentionally throw it out. Then there’s the ambiguity around where this half dustjacket is “meant” to sit. The spine of the book suggests it belongs at the bottom such that the publisher mark, author, and title on the cover and dust jacket line up but from the front or back cover any position looks correct and cuts the abstract design in satisfying ways.

The cover design is actually sort of haunting, at least as much as an abstract shape can be. There are all these moments in the book where Chayka feels something deep and profound in minimalist art that I just couldn’t imagine feeling until I realized maybe this Abraham’s design was doing exactly that to me. The design gave me a bit of déjà vu. At first, I thought it looked like the stylized S that everyone inexplicably drew on folders and bathroom walls in middle school. That wasn’t quite it though, the autobiographical period felt right but the engram itch was still there. The only place I was likely to encounter abstract art was in the underground concourse of Albany’s Empire State Plaza so I sought out the listing of all the art work hanging down there and recognized Al Loving’s work “New Morning I” which has a very similar tessellation pattern of diamonds that form the optical illusion of three-dimensional cubes when looked at just right. That still wasn’t quite it though.

I did not know who Al Loving was (again, I’m not a connoisseur of art) so I read his Wikipedia page. And there it was: Loving had created dozens of pieces for public spaces. Not just Albany’s concourse but train stations, college plazas, and theater lobbies. He was even a National Endowment for the Arts fellow in 1970, 1974, and 1984. (Eat it Tawny.) These shapes and their inoffensive colors are the aesthetic of late twentieth century public space, which is to say, the aesthetic of my early childhood. The Broward County library I grew up in, the classrooms I couldn’t wait to get out of. They all had something that looked like —but was not— a Loving. Repeated geometric shapes in over-stock industrial paint or heathered fabric stretched to a frame and hung on a wall. It wasn’t any one particular piece or even one artist, but a style that this artist was at the center of. As soon as this realization hit, I could practically smell the old molding carpet.

—

The book is divided into four chapters divided into eight short sections. In the introduction Chayka encourages the reader to treat the rest of the book as a “space” that can be explored in any order because “chronological history is too causal an approach for minimalism. Its ideas don’t have one linear path or evolution; it’s more of a feeling that repeats in different times and places around the world.” This nonlinear, choose-your-own-intellectual-adventure has been used to great effect by the likes of Paul Feyerabend in Against Method and Christopher Alexander’s A Pattern Language. Both of these books insist you have to read the whole thing (in fact the latter says the 1171-page volume is incomplete without having first read its 552-page companion The Timeless Way of Building) but they are broken up into small, more-or-less self-contained essays.

Alexander and his compatriots believe that most human problems were understandable as patterns. The size of a house or the decision-making structure of a group can be distilled into typified patterns with generic prescriptions. For example, pattern 161 “Sunny Place” notes that “we have some evidence—presented in [another pattern titled] south-facing outdoors (105)— that a deep band of shade between a building and a sunny area can act as a barrier and keep the area from being well used.” To avoid this shady barrier they recommend the following: “Inside a south-facing court, or garden, or yard, find the spot between the building and the outdoors which gets the best sun. Develop this spot as a special sunny place—make it the important outdoor room…” The reader can then follow Outdoor Room pattern 163 for more information. They might also check out fanciful patterns “wings of light” or utilitarian patterns like “bus stop.”

Why write a book like this? Why chop up your argument like a 90s sitcom storyline such that it is comprehensible in almost any order but most satisfying when completed? One reason is to help it fit into the reader’s life a bit easier. I was never more than four or five pages away from finishing a chapter of Longing for Less, which meant I could see why my phone had buzzed or I could go get a snack. This was minimal in the sense that the book’s ideas could seamlessly fit into small parts of the day, not unlike Erik Satie’s furniture music. The philosopher Ian Hacking in the 2007 reprinting of Against Method describes the features of this design like a YouTube product reviewer considering new iPhone features: “you can take it hitch-hiking or to a sit-in, and read a bit while you are munching on a few pilfered tomatoes or sheltering from a storm. You can pick up an idea, chase it, and relocate it in the Analytical Index, all the while being in a physical relation to the pages upon which you can scribble expostulations, if that is your wont.”

The analytical index of Against Method contains the author’s concise summaries of “the most interesting parts” of each chapter which themselves only last about a dozen pages or so. Feyerabend preferred to describe the book-shaped thing with the words “Against Method”on the cover as a “collage.” The effect of the collage is a fun performance of exactly what Feyerabend is arguing: that the history of science shows that there is no clear common structure across experiments. Similarly, you, the reader, can make up your own path through this epistemological argument. Any two people may take different paths but they both read the same book and have a common reality to talk about, and yet their method of getting there was totally different.

Chayka seems to want you to do the same, starting nearly anywhere by dipping into Japanese architecture, modern art, or Steve Jobs’ apartment. I started reading the chapter on Marie Kondo before going on to Steve Jobs, reading a few bits on Japan, and then slogging through the more art-centric bits. Without something like the Feterabend’s analytical index however, it was hard to make an informed decision about what to read and in what order.

No matter how elegant an author accomplishes this task it still feels like the technology of the book resists this genre. Unless it’s the Bible and you have hundreds of years’ worth of interpretation and guidance to make sense of each passage and verse, it is easy to get lost jumping around in a book you’ve never read before. I took to putting a check mark next to each chapter number to keep track of my progress. This helped a lot, but it didn’t prevent me from getting a bit lost when unfamiliar names popped up. Then I would have to read backwards until that person was introduced. I still saved the last few chapters for the end but was met with no synthetic conclusion, which was a little disappointing. Instead, and maybe this is fitting, Chayka leaves the reader in a Japanese rock garden to contemplate infinity.

Equally interesting is how the book is depicted as a digital object. Images of the book all have the half dust jacket sitting at the bottom, the location that the spine suggests it should sit. On Amazon the cover is fused into a single image, so you never know that the cube is only part of a collection of shapes. I imagine the ebook version also has the cover designed in this way. Perhaps the image is revealed on the last page “back” cover, I don’t know. Inside the text is a sans-serif font with generous margins, something that would be unknowable in a Kindle version that lets the reader change all of that. All the parts that make The Longing for Less a minimalist object are obliterated once it is packaged in a digital format, something that is so minimal(ist?) that it does not technically occupy space at all.

And like any good artist working in the minimalist style, Chayka is understandably annoyed by the misapplication of the term. In this case it is the easy observation that a book about minimalism isn’t very minimalist. His tweets leading up to the books sound like Judd just before he moved to Marfa (or at least Chayka’s description of him which, again, is my only knowledge of the guy) and his joke that his book “counts for negative five books” is a direct reference to Marie Kondo’s insistence that no one needs more than thirty. The joke is its own kind of summary of his book’s larger argument: that the trends of minimalism in Kinfolk-inspired Instagram photography and the popularity of Marie Kondo has only the most superficial relationship to the people who hated being called minimalists but definitely were.

The deeper minimalism, then, is closer to the shallow understanding than I think Chayka would be comfortable admitting. Because even if this current iteration of whatever is being called minimalist is detached from the longer, deeper history of the term in art, architecture, and music, then so is everything else. Minimalists are all standing in a circle facing outwards: a single, simple shape —a unity— but with each constituent participant looking somewhere else. There’s a centripetal force pulling them apart, even as that same force defines them as part of a group. So if, minimalism is a collection of “ideas [that] don’t have one linear path or evolution” and is instead “a feeling that repeats in different times and places around the world” then it seems cleaning out your room or judging a book by its cover, is as good a place to start as any.