Don’t tell the Israel Defense Force (IDF) that sharing videos from your Twitter account is ineffectual. They will point to their two-hundred thousand twitter followers that have generated 35 million views on their official Youtube account. They will extoll the virtues of a ruthlessly efficient and effective ad campaign that invites participation without the young Israeli even knowing they are engaged in two wars: a war of flesh as well as a war of mind. Granted, the IDF is no Justin Beiber, but it is hard to deny the impact of the IDF’s 30-person social networking team. The IDF’s social media savvy has not gone unnoticed. Technology and business publications have been more than happy to publish uncritical, lengthy interviews of top officials. This meta-propaganda usually begins by noting that Pillar of Defense was first announced through Twitter. The conversation will then turn to their complete arsenal: (Tumblr, Flickr, Facebook, Pintrest, and even Google+) before commenting on their brief tweet confrontations with Hamas. All of this happens almost apolitically. Every news pieces calls it propaganda, and yet it still has a powerful aesthetic and rhetorical effect. Social media is the Abrams tank of propaganda. Messages must navigate the harsh terrains of corporate and government-owned mass media and arrive safely in the minds of citizens. Unedited, unfiltered, pure. Social media can trample news cycles, navigate the minefields of editorial desks, and maintain total media superiority in the vacuum of Western under-reporting.

First, it is worth noting the similar language used to describe both social media and geopolitical conflict: campaigns, coverage, deployments, and engagement are common words used to describe a Twitter branding effort as well as a ground assault on a city. Military officers treat the media landscape like a battlefield and are constantly adapting to the idiosyncrasies of augmented warfare. Lt. Col. Avital Leibovich of the IDF told Buzzfeed that their Twitter strategy was to “respect the rules of engagement of that specific platform.” That means carefully following the terms of service and threatening the enemy with the detached, non-committal tone of a high schooler promising not to procrastinate. It is transparent, but maintains a necessary lie that keeps the relationship stable. The Atlantic’s Brian Fung later observed, “It’s an interesting turn of phrase, taking a traditionally military concept and applying it — so appropriately, as social media curators are always seeking ‘engagement’ — to digital communications platforms.” The language is eerily similar, and it is difficult to tell which came first, the war-like metaphors or their isomorphic sociotechnical structures. My analysis in this case is largely agnostic on this point for one simple reason: In times of war and empire, engaging one’s followers has always been just as important as engaging the enemy. Bloodshed has always been bookended by healthy doses of propaganda. Winning hearts and minds is as old as war itself. Selling the war –to potential draftees, to your allies, and to the opposition– has always taken the form of the dominant media platform of the day. We should have all expected, in the words of Huw Lemmy, “War 2.0 [to look like] the early drafts of a footwear campaign or a coffee franchise loyalty card scheme.”

Such reasoning sounds like technological determinism, but it is actually quite the opposite. Almost all of the interviews with IDF spokespeople describe an uninterested senior staff that are unconvinced of social media’s efficacy. It is only after pet projects produce tangible results that real resources are devoted to setting up and maintaing a social media presence. In an interview with Fast Company, Eytan Buchman (the head of the North American division of the IDF Spokesperson’s unit) describes the genesis of their social media division as if he were pitching a new iPhone app to a venture capital firm:

When flexibility and innovation reaches the communications world, suddenly it opens up new horizons. A number of years ago, one of our soldiers inside the foreign press branch suggested that we try to increase our social media presence. Initially, it was very grassroots inside the military. At one point, a soldier paid for a WordPress account using her own credit card just to get it off the ground instead of dealing with the military bureaucracy.

In the space of only a couple of years, it blossomed into a full-size branch with people who deal with all different forms of mediums–interactive mediums on a variety of platform and a variety of languages.

In doing research for this piece, I came across a Facebook conversation between Nathan Jurgenson and The New Inquiry’s editor Adrian Chen (@AdrianChen). They were discussing the previously mentioned Lemmy article on Facebook, and Chen made the excellent point that Lemmy, “doen’t distinguish between the official instagram photos put out by the IDF and the ones just taken by soldiers on their personal accounts.” Chen’s critique highlights one of the most important features of social media as propaganda. The “blossoming” described by Buchman can be read not only as an acknowledgement of social media’s power to deliver unedited propaganda to a global audience, but also as a revelation that propaganda can be crowdsourced. The state can conscript your body as well as your Instagram photos. The state military apparatus owns your augmented self, and it will use it as a weapon of awesome rhetorical and aesthetic power. As Lemmy describes it: “’These are the photos you would take if you served in the IDF,’ the aesthetic says, ‘we are just like you, and these military decisions are the ones you would take, if you were in our situation.'”

In doing research for this piece, I came across a Facebook conversation between Nathan Jurgenson and The New Inquiry’s editor Adrian Chen (@AdrianChen). They were discussing the previously mentioned Lemmy article on Facebook, and Chen made the excellent point that Lemmy, “doen’t distinguish between the official instagram photos put out by the IDF and the ones just taken by soldiers on their personal accounts.” Chen’s critique highlights one of the most important features of social media as propaganda. The “blossoming” described by Buchman can be read not only as an acknowledgement of social media’s power to deliver unedited propaganda to a global audience, but also as a revelation that propaganda can be crowdsourced. The state can conscript your body as well as your Instagram photos. The state military apparatus owns your augmented self, and it will use it as a weapon of awesome rhetorical and aesthetic power. As Lemmy describes it: “’These are the photos you would take if you served in the IDF,’ the aesthetic says, ‘we are just like you, and these military decisions are the ones you would take, if you were in our situation.'”

The picturesque self-documentation of the soldier, according to Lemmy and Jurgenson, creates a nostalgia for a battle-not-yet-finished. It appears as though it has already happened: decided, and valorized. This distance in time is bolstered by the social distance from state military authority. These dual psychological distances confer a deep sense of authenticity that can only come from a self-portrait. The result is near-perfect propaganda: personal, authentic, automatic, far-reaching, and instant. The speed by which military decisions can be contextualized and justified by formal and informal social media is the “killer app” of state-sponsored slacktivism. Within minutes, an entire soundscape of opinions, apparent first hand accounts, and official statements paints a picture of valiant defense against a ruthless enemy. Paul Virilio describes speed as the decisive advantage in war:

Speed is the hope of the West; it is speed that supports the armies’ morale. What ‘makes war convenient’ is transportation, and the armored car, able to go over every kind of terrain, erases the obstacles. With it, earth no longer exists. Rather than calling it an “all terrain” vehicle, they should call it “sans terrain” –it climbs embankments runs over tress, paddles through mud, rips out shrubs and pieces of wall on its way, breaks down doors. It escapes the old linear trajectory of the road or the railway. It offers a whole new geometry to speed, to violence. [Emphasis in original.]

Social media is the sans terrain vehicle of augmented warfare. It escapes the linear trajectory of the radio signal or the press release. It offers a whole new geometry to speed, to propaganda. Pillar of Defense has been under-reported in the United States, and the IDF’s social media is filling the information vacuum. As Joseph Flatley wrote in The Verge:

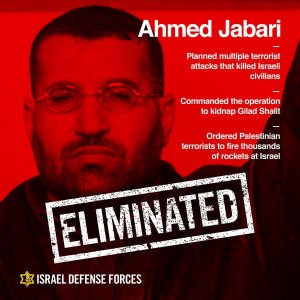

The latest Israeli offensive on Gaza is currently in its second day, and if you’re following the events you can get your news from a number of sources. Of course, the usual American news organizations are keeping an eye on the situation, and any major updates will make it onto their newsfeeds. (ABC News, for instance, has placed an item about yesterday’s hit on Hamas commander Ahmed Jabari beneath a story about a baboon that befriended a kitten in a zoo.) For those of you that prefer by-the-minute coverage, the Web 2.0 tradition of “liveblogging” is another alternative. RT America is doing a pretty good job with its effort, while I must admit that I’m a little disappointed by Al Jazeera’s liveblog, which has had but one sparse update all night. But the liveblog that captured our attention today is being maintained by the IDF itself.

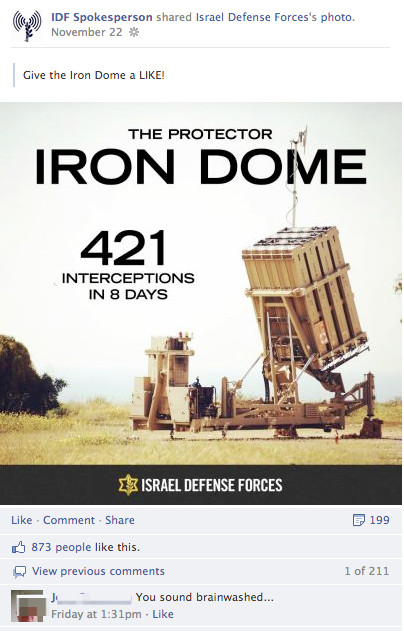

IDF’s tweets and blog posts are a running tally of rockets and resources. Hamas rocket attacks are crucial for justifying military action and painting the enemy as an unfeeling terrorist. Too many rockets and the IDF seems ineffectual. Too few rockets, and people start questioning your occupation. The result is somewhat contradictory and paradoxical: the IDF’s anti-missile defense strategy (aka Iron Dome) is described as extremely effective but is never depicted as impervious. In fact, daily rocket counts always include how many rockets they failed to intercept:

In last four days, nearly 500 rockets fired from #Gaza hit #Israel – another 267 were intercepted by the Iron Dome system.

— IDF (@IDFSpokesperson) November 18, 2012

Some numbers from the last 3 days: 492 rockets fired from #Gaza hit #Israel + 245 Iron Dome interceptions = 737 rockets fired at us

— IDF (@IDFSpokesperson) November 17, 2012

809 rockets fired from Gaza hit #Israel + 389 Iron Dome interceptions = 1,198 rockets fired at us #IsraelUnderFire

— IDF (@IDFSpokesperson) November 20, 2012

The IDF Facebook page is slightly less deprecating and omits the missed rockets. It also asks the reader to “like” their multi-million dollar anti-missile defense system. The critical comment hanging at the bottom of the propaganda serves to affirm the idea of the state as a peace keeping body, not as an occupying force. It will not censor its citizens or detractors because that is something done by governments with something to hide. More pragmatically, it is better to “engage the enemy” on your own turf where you can rest assured that fans will defend you and Facebook will collect everyone’s data. You have the higher ground.

While you might have the higher ground, the home field advantage, you must still follow the “rules of engagement.” The IDF’s assassination video of Hamas commander Ahmad Jabari was removed from YouTube but, according to the Associated Press, “Google Inc., which owns Youtube,… reconsidered and restored it.” The high ground is not totally safe. It has its own set of unique dangers. The IDF has warned citizens to turn off the geotracking when using Twitter and Instagram near Hamas strike zones. The high ground metaphor begins to break down, when we consider who is granted access to this position of power. While the IDF tweets from an officially verified account, Hamas’ own @AlqassamBrigade is under constant threat of banishment. The allotment of American-made information technology follows the paths of our weapons technology: the lion’s share goes to the Israeli military and, despite the government’s best efforts, some of it gets to Palestine. But just as weapons manufactures find loopholes to sell their wares to the markets that demand them, social media companies will get their services in the hands and modems of as many people as possible. After all, the Tweets Must Flow.

Social media is a major development in the creation and delivery of propaganda. It can avoid the editor’s desk and reach the discerning eye of the cynical news reader with its authenticity in tact. It can be called out as propaganda, and still “work” because it also serves as the arena for political debate. “Perhaps our own messaging won’t persuade you, but your fellow Facebook users might.” The “blossoming” of informal and undirected social media content –Instagramed photos of teenagers reporting for duty and Facebook posts from shell-shocked homes– convince even some of the most skeptical. No single post will have this effect, thus it is the institutional orchestration and curation of social media that is crucial to gaining the most benefit from social media. Without the attention to organizing individual efforts, the messages appear as disjointed blathering. It is only in the aggregate, indeed in the act of aggregating itself, that states (and yes, even social movements) produce coherent and effective propaganda campaigns. Without the collective effervescence you are just another person yelling on the Internet, not getting anything done.

Comments 4

Jeremy Antley — December 4, 2012

David,

Great post. A very interesting turn that demands more examination.

One example I immediately thought of, when reading your post, dealt with the role of propaganda in the Soviet Union. While the Soviet authorities certainly kept a very tight control over the various public 'organs', the efforts by the IDF described above certainly have some mirrors to the way the Soviet government utilized propaganda in shaping the public opinions. With regards to military language, much of the early Soviet propaganda emphasized the contest between Socialism and Capitalism in highly militarized terms. One exemplar of Soviet Realism, the novel 'Time, Forward!', is rife with this kind of language, the central plot line focusing on cement pouring worker's brigades and the breaking of established production records, all in the name of 'building' socialism and making a new world.

On the issue of conscripting the body and one's photos, a similar phenomenon in Soviet terms might be Stakhanovism- the promotion in press and novels of record breakers in industry or production, named after Alexsei Stakhanov, a record breaking Donbass Coalminer. Shelia Fitzpatrick's book 'Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times- Soviet Russia in the 1930's' has a wonderful section on Stakhanovism and hero promotion in general.

"Stakhanovites...were supposed to be not only record-breakers but also rationalizers of production. ...These were ordinary people- workers, kolkhoziniks (collective farm workers- JA), saleswomen, teachers, or whatever- who suddenly became national media heroes and heroines... Stakhanovites' photographs were published in the newspapers; journalists interviewed them about their achievements and opinions..." (74)

In the same way you highlight that self-documentation by IDF forces creates a 'nostalgia for a battle-not-yet-finished', one could argue that Stakhanovism shared the same goal vis a vis Socialism, in that these glorified workers appeared to be the model of the new Socialist order with their beaming pride in the state and proved dedication, through labor, of a desire to build the Socialist state. The goal has not been achieved, but the effect is to allow everyone to bask, through media, in the supposed fruitful gains the Stakhanovite embodies.

Social Media does allow the IDF to utilize propaganda in much more subtile ways when compared to the more direct involvement of Soviet propaganda efforts, but in many ways the ultimate goal of propaganda (which you hit upon) is to engage your 'supporters' and align them with the interest of the authorities.

In Their Words » Cyborgology — December 9, 2012

[...] “Social media is a major development in the creation and delivery of propaganda” [...]

An israeli — December 12, 2012

The IDF was not reporting on rockets it 'missed'. A shallow acquaintance with the Iron Dome concept would have clarified that it only targets incoming rounds that are likely to land in populated areas, ignoring those destined to empty spaces.

Eliahu Ha-Navi — December 12, 2012

> In fact, daily rocket counts always include how many rockets they failed to intercept:

No, they don't. Only rockets heading to populated areas are targeted, the rest is ignored by the system.

> The critical comment hanging at the bottom of the propaganda serves to affirm the idea of the state as a peace keeping body, not as an occupying force.

If the Facebook page is focusing on the Iron Dome as a defensive system, then that's exactly what the state is - an investor of resources in defensive systems to keep the population safe from the more than 12000 rockets fired at it. Gaza has not been occupied since 2005.

It seems your basic premises need more thought.