Abstract

Abstract

To those living within the central zones of large cities worldwide, homelessness has become a common way of being. However, in suburban and rural areas it may be hidden or even nonexistent. Despite the extreme wealth of the United States, homelessness has been growing steadily and spiking during economic recessions. Even though it is the homeless who suffer the most and die young, the political, justice and governance systems do the bidding of landlords and real estate development companies. Once a family is forcibly evicted from their home, they become the outcasts of society, targets of abuse and victims of poor health and short life expectancies. Even those who cycle in and out of homelessness become victims of these same tribulations. Few generalizations can be made about global homelessness because of different definitions of homelessness across borders and disagreement on what constitutes a home. What is most visible and problematic worldwide is the homelessness suffered by refugees, asylum seekers, and other immigrants. Due to the sharp rise in refugees from African and Middle Eastern armed conflicts, combined with the growing prejudice toward refugees and migrants, global homelessness will continue to perpetuate human suffering on a massive scale.

A Personal Anecdote

After living for 30 years in the suburbs of the Minneapolis and Saint Paul, Minnesota, I moved to the downtown inner city of Saint Paul. During those three decades in the suburbs, years would go by without seeing a homeless person or even non-white persons. Now living downtown, my wife and I both encounter homeless people and ethnic minorities every day of the year because we walk the second-floor skyways to get around downtown and for daily walking. The homeless also like the skyways to keep dry when it rains and warm when it snows. Saint Paul, a city of 300,000 had an estimated homeless population of about 1,500 in 2015 (Wilder Research 2016). The majority of the homeless in Saint Paul hangout in or nearby the downtown area.

Sharing narrow walkways in downtown Saint Paul with homeless people makes me feel part of the whole community, but when they relieve themselves on a carpet or block foot traffic while sleeping in a hallway, it is easy to wish they would to go elsewhere.

The homeless became and remain homeless largely from structural conditions in society such as lack of affordable housing, lack of jobs, and absence of social services for the homeless. In America, many have ignored the homeless except to complain about them and many of us have given up trying to improve their quality of life because we blame them for being lazy, crazy and dangerous.

Only if we spend time with some of them can we expect to learn how to help resolve their problems. Because some of the homeless are dangerous, we work with the City and Skyway Police to let them know about those appearing to violate the City criminal and skyway codes. We also work with a group of volunteers called “Ambassadors,” who befriend teenagers in the skyway to keep gang fights from erupting. It is not easy, but we try to establish a sense of community so that we help each other deal with urban living. The remainder of this article reviews the big pictures of homelessness in America and around the world, offering some approaches to address the problems head on.

Homelessness in the USA

Dwelling places such as caves and houses protect human life from threats of all types, but especially illnesses due to exposure and other harmful threats. Construction of houses that retain heat and reduce the human susceptibility to pneumonia and other weather-based diseases has increased life expectancy. Despite the obvious benefit of good housing, as the world economy has grown steadily, so has homelessness.

While one can make a long list of causes of homelessness, the greatest historical force underlying homelessness is the rapidly rising cost of housing in large cities. Huge inflation in the cost of housing (both renting and owning) continues at the same time that people have to move from rural to urban areas to find employment.

In this analysis, after considering trends, causes, and solutions of homelessness in the United States, the challenge of world homelessness will be discussed and analyzed. Some indicators of homelessness in the United States are shown in Figure 1. The top trend line represents the rise of homeless children (age 17 or younger) in the USA over the past decade, with a current estimate of 1.5 million children, which includes both children in homeless families and children not living in families (AIR 2014).

Figure 1. Homelessness in the United States over Time

The bottom two lines represent homeless adults, with the first line showing those living in emergency or temporary housing shelters and the second line for those living in other places such as under bridges, on sidewalks, in tents and so forth (HUD 2017). The 2017 count by HUD of the homeless is about 550,000 in the United States.

There has been a slow decline in adult homelessness over the past decade. The decline in adult homelessness while the number of homeless children has risen reflects two factors. One is that the vulnerability of children to being homeless is fairly recent and in part a result of the economic recessions of the past two decades. Another reason for the difference may be that the count of children was done by AIR (2014) and its Center for Family Homelessness, who extracted the estimates of child homelessness from a combination of U. S. Census data and counts from the U. S. Department of Education.

On the other hand, the estimates of adult homelessness were obtained from a single point-in-time survey of American adults staying in shelters or known outside locations during a specific night in January. The fact that their estimates of adult homelessness are so low compared to those for children suggests that many homeless adults were not found for the survey. People who slept in their cars, in a friend’s basement, a domestic violence shelter, a motel, a hidden shanty town, or at their workplace would not have been counted. Furthermore, the adult homelessness count is done by HUD (2017), an agency of the U.S. Government mandated to periodically report to Congress. The decline in homelessness on the part of adults may be due to the mandate that HUD has to build more housing units to be used by the homeless. HUD has to justify its existence by putting up housing units, which may be intended primarily for single adults rather than families with children.

Demographics of American Homelessness

Knowing the distribution of homeless by demographic factors such as income, age, and urban place may suggest policies and priorities for homelessness and housing insecurity. Such analyses can only be found within individual countries like the USA. Global studies do not have enough consistency across nations to make cross-country analysis particularly useful.

In Western countries, the large majority of homeless are men (75–80%), with single males overrepresented. However, the most prominent demographic factor is age, especially children versus adults. In the US, one in five homeless persons is a child under age 18. Most of these children stay in emergency shelters with an adult parent, but increasingly homeless children do not have an accompanying adult.

In the United States, the race/ethnicity of the homeless reflects the racial distribution of the larger population except that non-whites predominate. Nearly half of the homeless are White and 45% Black. Those staying in shelters are more likely to be African American than White.

Worldwide, as well as the United States, the homelessness population lives almost exclusively in cities rather than rural areas. Urban areas unintentionally help homelessness thrive by providing so many places for people to hide or disappear. In addition, cities, compared to the countryside, are much more likely to provide shelters and other services for the homeless.

Causes of Homelessness

- Structural Causes. The rising cost of new housing plus the high costs of maintaining housing are good examples of structural causes of homelessness. Other economic reasons for homelessness include foreclosures on home mortgages, costs related to home utilities, and loss of employment. All of these negative forces often lead to poverty, which tends to drive the pitfalls of homelessness. Forced eviction is another major structural cause of homelessness. (See below.) Underlying all of these economic forces of homelessness is economic structural inequality.

- Personal Causes. A variety of personal factors increase the chances of homelessness, especially untreated mental illness, substance abuse, posttraumatic stress disorder, lack of education, domestic violence, institutional commitment such as incarceration, foster care, and injuries. Failure to pay for critical insurance costs is another route to losing one’s house and the ability to pay for critical health expenses.

- Catastrophes and Disasters. Severe tragedies often leave victims without the ability to earn an adequate wage including sufficient money to pay for even very low cost housing. Divorce, job loss, and severe disabilities have the potential to become disasters too.

- Healthcare costs. If illness or injury incapacitates the home owner or makes it impossible to hold a job, chances are that he or she within a very short time will no longer have the funds for mortgage payments or rent. Upon eviction under such circumstances, homelessness cannot be avoided. The most problematic health-related costs are those of mental health treatment.

- Fraud. Unscrupulous mortgage companies and con artists destroy one’s ability to pay housing costs and other basic expenses, often with disastrous results.

- Forced Eviction. Hartman & Robinson (2003) reported that millions of low-income American families each year were forcibly removed, with their belonging, from their homes, even in the middle of Winter. In most other economically advanced nations, laws have been put in place that keep evictions from occurring in Winter’s coldest months (Desmond 2016).

Residential stability produces community stability and neighborliness. But poor families in the United States are involuntarily evicted at such high rates that the family system has little hope for the poor. The laws and law enforcement procedures favor the landlords rather than the human beings that need shelter. Eviction is not just an immediate tragedy; it produces long-term disadvantages, such as loss of jobs, less access to food and healthcare, and increased chances of incarceration. Desmond (2016) describes many such evicted families and the social chaos produced by current eviction procedures. He characterizes the suffering of the eviction system in America as “shameful and unnecessary…and as failing to guarantee a stable home” that meets the unalienable rights promised by the nation’s founders.

Policy Options for Reducing Homelessness

- Major Subsidies of Low Rent Housing. Communities, counties, states, and national, as well as private funds, can all contribute to offering incentives to investors to build apartment buildings with rents that the low-income can afford. Not only is it difficult to get developers to make such investments, but often the communities where subsidized housing is to be built, oppose the building of such units because they worry, often falsely, that property values in their community will plunge.

- Adequate Funding of Shelters and Services for the Homeless. In the typical American City, the funding of shelters and other homeless programs tends to be woefully inadequate. Such underfunding results not only from the crass attitude that the homeless should take care of all of their own needs, but funding is given low priority also because people fear that providing effective services for the homeless will only attract the homeless from other parts of the country.

- Job Training Programs. Emergency shelters could easily be expanded to include job development programs and work skills training for the homeless and chronically homeless. Programs for the homeless keep passing the buck on this service, so job training for the homeless remains rare.

- Establish Programs for Reduction of Mental Illnesses, Addictions & Incarcerations. The homeless population surged in the 1950s when under the influence of Ronald Reagan, mental institutions were closed. Many of the homeless continue to cycle in and out of jail and prison. And many, if not most, not only have become chemically dependent, but earn what little income they have from selling narcotics.

- Finding Hidden Homelessness. Some homeless subpopulations remain elusive and difficult to track. These include those who sleep in their cars, live in motels, those living in dense, overcrowded houses and apartments, and those who “couch surf,” that is, they sleep on other peoples’ couches and floors. Finding these subpopulations and providing assistance will likely reduce costs in the long run because these people for the most part have not yet begun to suffer from drug addictions and illegal activities typical of those in chronic homelessness.

- Implement Community–based Homeless Programs involving Citizens. Government cannot solve the homeless challenges alone. Nonprofit organizations, churches, and citizens need to be held responsible for turning the blight of homelessness into a homeless recovery system. Organizations and money cannot resolve the problems alone. We the people must be willing to change our negative stereotypes, demonstrate compassion and be willing to help. Perhaps the first place to start is with progress for the children who have fallen into homelessness quite innocently.

- Housing First. The homeless often need other social services such as drug treatment, healthcare, battered women’s assistance and so on. The policy of ‘housing first’ calls for attempting to provide adequate housing quickly before trying to provide all of the other services that a homeless person may need. Several hundred American cities have adopted Housing-First policies. In the long run, housing-first may be the most cost-effective policy when combined with job training and other related programs.

- Increasing Refugee Hosting Capacity. One of the most intransigent aspects of the global migration and homelessness challenge is the increasing political pressure within many host countries, especially those in the US and the EU, to stop letting more immigrants into the country and to stop providing them services. Thus, countries like the USA and the UK, which economically are best prepared to host refugees, increasingly are becoming the least likely to host them. Ironically, the countries hosting the most refugees, like Jordan and Lebanon, are economically under stress and unable to provide much for the millions of refugees in these poorer nations.

- Prevention of Homelessness. The longer people live as homeless, the more they become involved in drugs, crime, and other at-risk lifestyles. Therefore, from the standpoint of human and social capital, the quicker at-risk persons can be placed in longer-term housing, the healthier the society.

Housing Insecurity

Homelessness is sometimes called ‘housing insecurity,’ even though insecurity implies a broader range of risk taking than homelessness. Housing insecurity is an important concept in that it represents a state of economic insecurity such that the occupants may face difficulty in making the financial outlays needed to rent or own one’s home.

While the Gallup Poll does not ask about homelessness per se, it does ask if respondents “have enough money for shelter,” a good measure of housing insecurity. Using this indicator, in the United States from 2007 to 2016 the percent at risk for shelter rose 10% (from 2% to 12%.) Worldwide during that same period, those at risk for shelter went up 5% (from 18% to 23%.) While economic indicators for this period grew stronger giving the wealthier more income, prosperity did not trickle down to those who needed it for such essentials as shelter.

So far in this discussion, the focus has been on the United States alone. Now we consider homelessness worldwide, which is a much broader topic. Global homelessness is different principally because the developing world has a much more difficult time avoiding homelessness than does the developed world.

The principle reason for the greater challenge of homelessness in the developing world is migration pressures due to war and persecution. This results in very large flows of migrants looking for asylum, refugee status and a more secure environment in which to raise children.

World Homelessness

In addition to the Gallup Poll’s housing insecurity indicator, the Gallup World Poll has had a housing question: “Have there been times in the past 12 months when you did not have enough money to provide adequate shelter or housing for you and your family?” While responses to this question indicate the difficulty many have with finding enough resources to pay for housing, it does not fully capture the volume of people who live in a state of “hidden homelessness,” those who do not have a residence or an address because they live in such places as under bridges or sleep on somebody else’s couch.

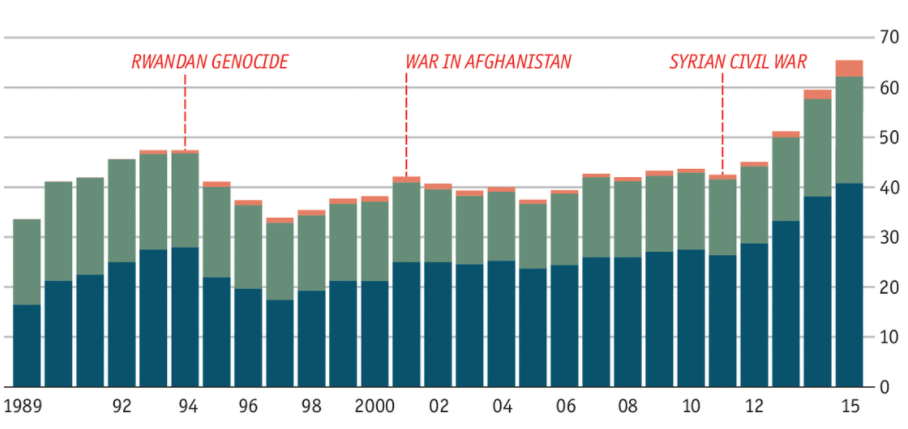

Fig. 2. Forcibly Displaced People Worldwide in Millions by Year (See note below chart.)

Note: At the tip of each bar is the count of people who have applied for asylum on the grounds of needed protection from the rules of their home country. The light shaded portion of each bar represents the count of refugees, and the dark part of each bar gives the count of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs).

Perhaps most seriously missing from the housing security indicator of housing risk are those whose status is ‘refugee’ or ‘immigrant’ and who live in temporary structures like tents. In addition, there are nomads and gypsies, who travel continuously and live in meagre tents with minimal and temporary protection from the harsh weather.

Fig. 2. Forcibly Displaced People Worldwide in Millions (See note below chart.)

The Figure above shows the count of people who were forcibly displaced from their homes, which in 2015 added up to about 65 million people. This count includes people who remained in their country, so they are labeled ‘displaced,’ and those who were able to reach another country, which means they were labeled ‘refugees.’ Those considered to be ‘asylum seekers,’ are those who hope to officially be considered refugees. Technically, those considered to be refugees have been found by the host country to be deserving of international protection and assistance.

The legal definition of homeless varies from country to country, and among different jurisdictions in the same country or region. Nevertheless, the last time a global survey was attempted, in 2005, an estimated 100 million (1 in 65 at the time) people worldwide were identified as homeless. More recently, the UN concluded that 1.6 billion people live homeless as squatters or live in temporary shelter, all lacking adequate housing (Habitat 2017).

Most countries provide a variety of services to assist homeless people. These services often provide food, shelter (beds) and clothing and may be organized and run by community organizations (often with the help of volunteers) or by government departments or agencies. These programs may be supported by the government, charities, churches and individual donors. While some homeless have jobs, some must seek other methods to make a living.

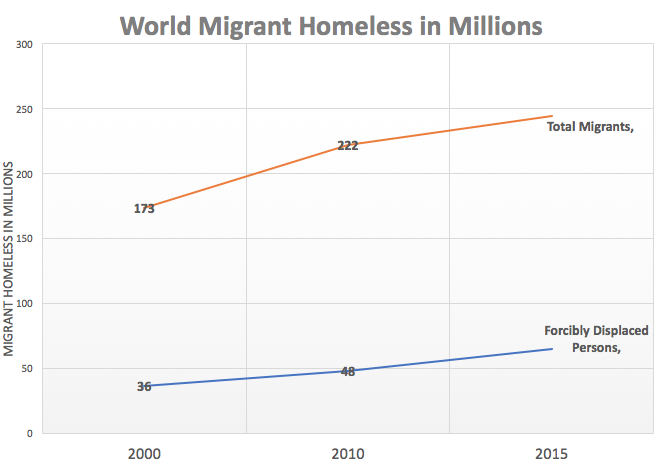

Figure 3. Global Homeless Migrants Trends.

Begging and panhandling are some of the income options for the homeless, but this option is not viable for homeless who lack the necessary social skills for this type of work. People who are homeless may have additional conditions, such as physical or mental health issues or substance addiction; these issues make resolving homelessness a challenging policy issue.

Goals for the Reduction of Homelessness

Several UN projects including the project on Sustainable Development Goals, which has been abbreviated to ‘Global Goals,’ articulate highest priority goals for global human improvement. So far, only one Global Goal specifies housing issues, Global Goal No. 11. It advocates: “Making cities safe and sustainable means ensuring access to safe and affordable housing, and upgrading slum settlements.” From this analysis of homelessness, we can specify four additional goals or sub-goals for housing as follows.

Goal H.1. Prevent and end chronic homelessness • Chronic homelessness generally is defined as continuous homelessness for at least 12 months or 12 months of episodic homelessness over three years. To avoid the permanent damage of chronic homelessness, major steps need to be taken. For example, HUD in the United States, between 2010 and 2017 installed nearly 100,000 more permanent supportive housing (PSH) beds dedicated primarily for people with chronic patterns of homelessness.

Goal H.2. Prevent and end homelessness for youth and children as well as their families • As noted earlier, research found a rapidly rising number of children in homelessness in the United States. Children are particularly vulnerable to negative consequences from homelessness, so this is an extremely important goal.

Goal H.3. Set a path to ending all types of homelessness • As already noted, many different variations on homelessness exist, including their causes and the consequences. This goal specifies that comprehensive solutions are needed because of the wide variation in the nature of the problems of housing insecurity.

Goal H.4. Develop Strategies to Induce Wealthier Nations to Host more Immigrants • The five wealthiest countries are among the nations least likely to host a proportionately large number of refugees. In contrast, the five countries that host the most refugees are all relatively small and poor. This rising flow of migrants into wealthier countries is often blamed for the increasing rise of nationalism among the wealthiest countries.

Over the past 10 years, research has been conducted to determine whether the wealthy or the poor are more likely to feel compassion and generosity toward poor people who need resources to live healthier lives. The strong conclusion of these research studies is that the rich are less likely than the poor to be generous and compassionate toward the poor (Grewal 2012). So, it is not the pervasive nationalistic ideologies that account for the rejection of the homeless by the wealthier groups and countries, but the lack of empathy on the part of the rich, which accounts for their failure to help those in distress (Daniels 2014).

Conclusions

A home is not just a physical space, but a social space that can provides roots, identity, security, a sense of belonging and a place of emotional wellbeing. Thus, houses provide critical contexts for maturing safely from infancy to childhood and later transitions to adulthood and beyond. The homeless have a much higher chance than home-dwelling Americans to be at risk of addiction, suicide, mental health, incarceration as well as individual risk factors such as family conflict, divorce and weak support networks (Lee, Tyler & Wright 2010).

Recent estimates of the homeless population in the USA suggest that about 550,000 live as homeless on any one night. But these one-shot studies miss a lot of the squatters, those living in well-hidden areas. Homeless people and homeless organizations are sometimes accused and convicted of fraudulent behavior. Homeless criminals have exploited their status with identity theft and tax and welfare scams. These incidents, of course, lead to negative stereotypes for the homeless as a whole. Most countries provide services to assist homeless people. These services often provide food, shelter and clothing and may be organized and run by community organizations (often with the help of volunteers) or by government departments or agencies. These programs may be supported by the government, charities, churches and individual donors. While some homeless have jobs, some must seek other methods to make a living.

The concept of the American Dream builds upon the stability and solidarity that having and keeping a home provides. The American Dream shifted over the past 65 years from protecting people’s homes to protecting the landlords right to exploit their renters. Desmond (2016) proposes that the housing system be rebalanced by expanding our housing voucher program for all low-income families and that landlords not be allowed to decide not to rent to the homeless with vouchersd. Ironically, most housing subsidies in America now go to those with upper-middles class incomes, not the low-income households that really need it.

Desmond’s 2016 book, Evicted, tells story after story of the intense, multi-dimensional suffering that poor, mostly minority families experience when they and their belongings are literally pushed onto the sidewalks in front of their homes, often in the dead of winter, by bullying sheriffs. In these situations, those doing the evictions have all the power and work on behalf of the land owners, not the home occupants.

According to Willse (2015), “Homelessness is a crowded house full of so much death and disease that there is hardly room enough for what should be a great excess of social and political shame.”

References

American Institutes for Research (AIR). (2014). America’s Youngest Outcasts: A Report Card on Child Homelessness. Waltham, MA: The National Center on Family Homelessness at American Institutes for Research.

Daniels, A. (2014). As wealthy give smaller share of income to charity, middle class digs deeper. The Chronical of Philanthropy. Accessed on 12 Dec. 2017 at https://www.philanthropy.com/issue?cid=UCOPNAVTOP

Desmond, M. (2016). Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City. NYC: Crown/Archetype.

Grewal, D. ( 2012) How Wealth Reduces Compassion. Scientific American. Accessed on 21 Dec. 2017 at https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-wealth-reduces-compassion/

Habitat (2017). The Case for Habitat. Habitat for Humanity. Accessed 14 Dec. 2017 on http://www.habitatmidohio.org/about-habitat/the-housing-crisis/

Hartman, C. & Robinson, D. (2003). “Evictions: The Hidden Housing Problem,” Housing Policy Debate. 14: Pp. 461–501.

Lee, B. A, Tyler, K. A & Wright, J. D. (2010) The New Homelessness Revisited. Annual Review of Sociology 36, Pp 501-521.

Link, B. G., Phelan, J, Bresnahan, M, Stueve, A, Moore, RE, Susser, E. (1995). Lifetime and five-year prevalence of homelessness in the United States: new evidence on an old debate. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 65, Pp. 347–354.

Ortiz-Ospina, E. & Roser, M. (2017) – ‘Homelessness’. Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Accessed on 14 Dec. 2017 at https://ourworldindata.org/homelessness

United Nations (2008). UN-HABITAT Unveils State of the World’s Cities Report. London, UK: UN-HABITAT.

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). (2017). The 2017 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. Accessed on 14 Dec. 2017 at https://www.hudexchange.info/resource/5639/2017-ahar-part-1-pit-estimates-of-homelessness-in-the-us/

Wilder Research. (2016). Homelessness in Minnesota: Findings from the 2015 Minnesota Homeless Study. Saint Paul, MN: Wilder Research. Accessed on 20 Dec. 2017 at https://www.wilder.org/Wilder-Research/Publications/Studies/Homelessness%20in%20Minnesota%202015%20Study/Findings%20from%20the%202015%20Minnesota%20Homeless%20Study.pdf

Willse, C. (2015). The Value of Homelessness: Managing Surplus Life in the United States. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Comments